Released in November 1974, Kraftwerk’s ‘Autobahn’ remains a touchstone of modern electronic music. Here, Bruce Tantum revisits its genesis and, with the help of Justin Strauss, Kevin Saunderson and Arthur Baker, maps out its seemingly infinite influence

It’s the middle of the 1970s, and in the middle of a mall parking lot in the middle of New Jersey, a child is sitting in the family sedan waiting for his mother to finish shopping. The AM radio is playing full blast, pumping out the solid gold hits of the day — Tony Orlando & Dawn, Leo Sayer, Sammy Johns’ ‘Chevy Van’ — when suddenly a tune starts playing that, in its sheer otherness, immediately demands full attention.

It commences with the sound of a slamming door and a car ignition. A loping rhythmic pulse, not played by any recognisable instruments but by something far more alien, anchors a bright melody that’s simultaneously elegant and robotic. There are no obvious guitars, and only the barest hint of percussion, which sounds like no drum kit the kid has heard before. The lyrics hit his ears in a language he doesn’t quite recognise: “Wir fahr’n, fahr’n, fahr’n, auf der Autobahn”. Three and a half minutes of transcendent pop later, it’s over, and the boy’s musical world is changed forever.

The track was, of course, Kraftwerk’s ‘Autobahn’ — a truncated edit of their fourth album’s titular 23-minute track. The kid was me, and I’m far from the only one who was irrevocably changed by the experience of hearing it for the first time. For many who were alive back then, ‘Autobahn’ altered music’s definition: it fundamentally changed their ideas about instrumentation and innovation. In its synthesised simplicity, it reconfigured the very notion of what popular music could be.

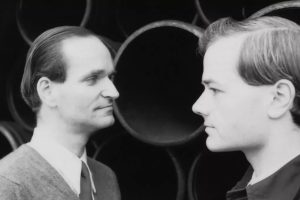

Even people born decades later — producers, DJs, anyone with any interest whatsoever in electronic music — are only ever a few degrees of separation away from its effect, which remains as potent as ever today. In truth, ‘Autobahn’ set Kraftwerk on course to become one of the most important musical acts of all time. With Ralf Hütter and the late Florian Schneider at its core, the Düsseldorf outfit’s influence is felt keenly in the foundations of everything from hip-hop, electro and techno to synth-pop and post-punk.

Five decades since the release of ‘Autobahn’, and amid an extensive tour celebrating this milestone, it feels worthwhile to revisit its genesis, and map out Kraftwerk’s enduring resonance.

Düsseldorf has long been a business-oriented city, but in the late 1960s, its arts scene was thriving, with movements like Fluxus and Pop Art inspiring new ways of thinking, experimenting and creating. Futurism, with its emphasis on dynamism and technology, caught the interest young Hütter and Schneider, who first met as students in 1968 — the Futurist polymath Luigi Russolo, author of the 1913 manifesto The Art Of Noises, has been cited as a particular influence on the pair.

The same could not be said for popular music in the city during that decade: North American and English rock and pop dominated the German airwaves alongside the easy-listening sounds of European Schlager. Some, however, yearned to break free from that model in search of something more progressive. In his book, Kraftwerk: Future Music From Germany, Uwe Schütte wrote: “Hütter and Schneider belonged to the smaller group of people who were unhappy that the young post-war German generation possessed no culture of its own, only pale imitations of Anglo-American models. A new, genuinely autonomous type of music was needed to express a new German identity.”

Düsseldorf’s Creamcheese club, a regular haunt of Hütter and Schneider, became a nexus of this emerging movement. Founded in 1967 and named after a Frank Zappa character, the music and arts venue played a key role in the proliferation of “krautrock” and “kosmische”, loose terms used to describe music characterised by avant-garde psychedelia, free-form improvisation and the minimalistic 4/4 rhythm that became known as motorik. Foundational acts like Can from Cologne and Berlin’s Tangerine Dream passed through there, and in 1971 it hosted one of Kraftwerk’s earliest live concerts.

Before that, Hütter and Schneider were members of a band called Organisation — full name: Organisation zur Verwirklichung gemeinsamer Musikkonzepte — with the former on Hammond organ and the latter on flute, electric violin and percussion. Largely improvised, the band’s music alternated sound-as-sound experimentation with passages that loosely fit into the krautrock template. An album, ‘Tone Float’, was released in the summer of 1970, with the fabled studio whiz Conny Plank sharing production duties with the band, but following poor sales, they were dropped by their label. Hütter and Schneider jumped ship, and Kraftwerk was born.

Their first two albums — 1970’s ‘Kraftwerk’ and 1972’s ‘Kraftwerk 2’ — followed much in the same mode as Organisation, with Plank returning for co-production duties on both. But even then, there were flashes of what Kraftwerk would eventually become: the gliding flute tones and propulsive rhythm that open the first LP’s ‘Rucksack’; the pulsing cadence of the second album’s ‘Klingklang’; the shards of aural abstraction and tape echo that punctuate traditional formations of guitar, flute, violin, organ and drums.

The live sets that corresponded with these albums would prove equally prophetic: watch their performance from Rockpalast 1970 on YouTube to get a sense of the undiluted musical experimentation that fuelled Kraftwerk’s momentum in those early days. It’s wild.

On 1973’s ‘Ralf & Florian’, Hütter and Schneider (and Plank) further established the classic Kraftwerkian style — there was a greater emphasis on electronics than either of the previous two LPs, and a simple drum machine makes its presence known, notably on the standout track ‘Tanzmusik’. Another cut, ‘Ananas Symphonie’, marked Kraftwerk’s first use of processed vocals, something that would become a staple of their music, most notably in the opening seconds of ‘Autobahn’.

If ‘Ralf & Florian’ was a series of baby steps toward a new, uniquely Kraftwerkian kind of music — “the sound of clean, modern air blowing out the late ’60s/early-’70s templates,” as Tony Marcus wrote for Fact in 2008 — ‘Autobahn’ was a great leap; its synthesised, machine-tooled sheen was a bold foray into music’s future.

In the band’s early years, Hütter and Schneider worked with a rotating cast of musicians, both in the studio and their live shows. These included guitarist Michael Rother and drummer Klaus Dinger, who went on to form another pioneering Düssedorf band in 1971, Neu! For ‘Autobahn’, the core duo enlisted Klaus Röder and Wolfgang Flür; all four are visible in the rear-view mirror of the now-iconic album cover’s highway imagery. (In the UK, that cover was replaced by a blue logo.)

Flür, a percussionist who was a Kraftwerk member right through to their 1986 album ‘Electric Café’, worked with a Farfisa Rhythm Unit 10 and Vox Percussion King, along with custom-built drum pads. Recorded in both Plank’s studio in nearby Cologne and Kraftwerk’s own Kling Klang studio, other instruments included the Minimoog and the ARP Odyssey, with bare touches of Röder’s processed guitar and flute introduced for added colour.

The title cut, filling up the record’s entire A-side, is an homage to Germany’s Bundesautobahn, the famed array of roadways that link the country’s regions. The lyrics, written by Hütter, Schneider and their poet-artist friend Emil Schult — who also created the LP’s cover, and co-wrote later Kraftwerk tracks like ‘The Model’ and ‘Pocket Calculator’ — are both seriously deadpan and earnestly utopian. Delivered in German sprechgesang, they translate as follows: “Before us is a wide valley / The sun shines with glittering rays / The road is a gray band / White stripes, green edge / Now we are switching the radio on / From the speaker sounds / We drive, drive, drive on the Autobahn.”

In a 1991 interview with Mark Dery for Keyboard magazine, Hütter summed up what Kraftwerk was up to on ‘Autobahn’, and indeed, throughout their discography. “Our music is electronic music, but we like to think of it from the German industrial area — ‘Industrielle Volksmusik’. It has to do with a fascination with what we see all around us, trying to incorporate the industrial environment into our music.” If you think of the open road as a key component of that environment, that’s about as concise a description of Kraftwerk’s philosophy during the creation of ‘Autobahn’ as you’ll find.

The lyrics’ matter-of-factness matches the minimalistic music, but it all adds up to much more than the sum of its parts. Upon its release, however, ‘Autobahn’ was largely ignored by the traditional rock press, unaccustomed as it was to anything even vaguely electronic. Nevertheless, the LP reached No. 4 on the UK albums chart and No.5 in the US. It hit similar numbers across the world, with the abridged single charting widely as well. Whatever magic was at its core, it created what is arguably the first electronic pop masterpiece.

“I had never really heard anything like ‘Autobahn’. I was blown away by it — by the emotion and humanity they brought to those machines. It opened my mind to the possibilities of electronic music at a time when I definitely wasn’t thinking about that at all.” – Justin Strauss

The veteran New York DJ and producer Justin Strauss has led a life in electronic music, but in the mid-1970s, he was a rising rockstar in the power-pop combo Milk ‘N’ Cookies. In 1974, when the young band travelled to London to record their self-titled LP for Island Records, ‘Autobahn’ — both single and album — were moving up the worldwide charts.

“I turned on the TV to this Top Of The Pops kind of show, and there was a promo clip of ‘Autobahn’,” he recalls. “We were into glam and Bowie and T. Rex then, and I had never heard of Kraftwerk. My father had these albums from Perrey and Kingsley — these weird little synthesiser records — and obviously the Beatles had been experimenting with electronics, but I had never really heard anything like ‘Autobahn’. I was blown away by it — by the emotion and humanity they brought to those machines. It opened my mind to the possibilities of electronic music at a time when I definitely wasn’t thinking about that at all.”

Arthur Baker, the legendary record producer who’s worked with everyone from Tina Turner and Diana Ross to New Order and Freeez, concurs, though the track’s impact was perhaps less obvious to him at first. He recalls working at the Boston record shop Soundscope when ‘Autobahn’ hit the shelves. “Back then, I was into everything,” he remembers. “The Temptations, Sly and the Family Stone, the Allman Brothers, Bowie, ‘Dark Side of the Moon’, just everything… It was the beginning of disco, too, with Blue Magic, MFSB and all that Philly stuff.”

None of which have much in common with ‘Autobahn’, but once the album arrived in the shop, he played it over and over again. “At the time, I didn’t think of it as like, ‘Oh, this is going to create a new sound’,” Baker says. “But we played it so much in the store, I think it probably did have some effect on me.”

Though Baker had familiarity with the concept of electronic music at this point — he had taken a class with the composer and educator Everett Hafner at Hampshire College — he initially felt ‘Autobahn’ was a bit gimmicky, owing in part to the similarity between its “fahr’n, fahr’n, fahr’n” vocal and the Beach Boys hit ‘Fun, Fun, Fun’. (Hütter has repeatedly denied any explicit Beach Boys’ connection to the song, their similarity shrugged off as pure coincidence.)

Nonetheless, by the turn of the next decade, Baker was fully sold. In 1981, he collaborated with the noted New York-based Kraftwerk fan Afrika Bambaataa to create Soulsonic Force’s ‘Planet Rock’, a single that interpolated elements of their tracks ‘Trans-Europe Express’ and ‘Numbers’ to become a seminal work of North American electro.

Kraftwerk’s music played an equally significant role in the birth of techno in Detroit. Celebrated local radio DJ The Electrifying Mojo had been an early adopter of their records, and by the late ‘70s was regularly spinning tracks of theirs like ‘Trans-Europe Express’ and ‘We Are The Robots’ on air. Upon hearing their music for the first time, one regular listener, a fledgling electronic musician by the name of Juan Atkins, was left with his jaw on the floor.

Speaking to Electronic Beats in 2012, he explained: “It just sounded so new and fresh. I mean, I had already been doing electronic music at the time, but the results weren’t so pristine — the sound of computers talking to each other. This sounded like the future, and it was fascinating, because I had just started learning about sequencers and drum programs.”

“Kraftwerk definitely influenced my sound, because when I heard their music I automatically knew I had to tighten up what I was doing,” he added. “I had to make it cleaner and better.”

Atkins and his companions in The Belleville Three pioneered techno on their own terms, but the influence of Kraftwerk, like that of Parliament-Funkadelic, doubtlessly played a role in what they created. In Atkins’ case, this is perhaps most evident in his early electro work with Richard “3070” Davis as Cybotron, most notably in their game-changing track, ‘Clear’.

Fellow Detroit techno pioneer Kevin Saunderson recalls first hearing ‘Autobahn’ when he was in the seventh grade, around the same time Atkins was first amassing his array of synths. “Later, when I started creating music, I thought about what I could do on my own,” Saunderson recalls. “It was Kraftwerk, as well as Juan, who let me know it was possible. They helped to inspire me to make electronic music.”

“They’re the foundation,” he adds, “and yet they still sound like nothing else out there. What grabbed me was that they sounded like music from the future.”

The decades may have passed, but ‘Autobahn’ retains that futuristic sheen. “It was so ahead of its time that it’s still kind of ahead of its time,” Strauss says.

Truly, even if you’ve heard ‘Autobahn’ in its full-length glory a thousand times over the years, its effect remains transportive in every sense of the word. You might find yourself in blissed-out reverie, feeling the wind blow through your hair as though you’re speeding down an open road. It’s a serenade to movement, particularly in its propulsive middle section. (The zooming car effects might seem a bit hackneyed now, but at the time of its release, it certainly blew a few minds.)

The song’s coda, with its fluttering textures, graceful melody and wistful vibe, signifies the journey’s end. “It’s basically the musical description of a car journey from Düsseldorf to Hamburg,” Wolfgang Flür said in Rudi Esch’s indispensable 2015 book Electri_City: The Düsseldorf School Of Electronic Music.

But it’s much more than that prosaic description suggests. At its core, ‘Autobahn’ is an ode to traveling somewhere new, to hurtling towards new sonic paradigms with eyes fixed squarely on the horizon. Equally, it’s a touchstone of pop minimalism, its significance hiding behind surface sheen and subtle drama. Existing in the shadow of the title cut, the B-side pales in comparison, though with tracks like the pastoral ‘Morgenspaziergang’, it certainly has its moments of beauty.

‘Autobahn’ didn’t just influence electronic music artists that followed, it helped set the stage for much of Kraftwerk’s later work. Its emphasis on movement is reflected in songs like ‘Trans-Europe Express’; the motorik rhythm of its middle section gets a replay in ‘Spacelab’; the effortless flow of its final minutes is felt in ‘Europe Endless’. Those lyrical stylings – deadpan as they are delightful — can be found in nearly every Kraftwerk song there is.

Unsurprisingly, ‘Autobahn’ still soars in a live setting. In March, the group — now comprising Henning Schmitz, Falk Grieffenhagen, Georg Bongartz and Hütter, standing as always behind his gear at the left of the stage — played at New York’s Beacon Theatre as part of their ’50 Years of Autobahn’ tour, which also saw them play Coachella for the first time since 2008. Running through revitalised versions of crowd favourites — ‘We Are The Robots.’ ‘The Model’, ‘Trans-Europe Express’ — one track, half a century old, still holds a power unlike any other.

The song’s accompanying retro-futuristic visuals, Volkswagen Beetles and Mercedes sedans coursing through a primary-colour landscape, hint at an immaculate utopia — a streamlined nirvana free from troubles, everything working as it should, perfection as reality. That wonderland, of course, is a fantasy in most aspects of life — but musically, we’re in the thick of it, and Kraftwerk helped take us there.

![Carl Cox says his Ibiza residency at [UNVRS] will be a “whole new world” (DJ Mag)](https://www.myhouseradio.fm/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/carl-cox-1.jpg-500x383.webp)

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.