In South Africa’s burgeoning ballroom scene, pioneering figures and DJs are finding their own ‘Ha’ in the country’s past, and in the contemporary sounds of gqom, amapiano, and Afrobeats. Tazmé Pillay learns more

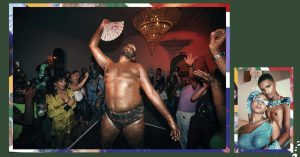

“DJ, cut the beat.” The room falls silent — an unforgivable sin anywhere else, but this is no nightclub. This is a ball. The competitors on the runway freeze mid-battle. The crowd murmurs, “Is it a chop?” On the mic is pioneering house mother Cheshire Vineyard. Here, their word reigns supreme. A rogue guest, oblivious to the rules of the house, has stormed the stage. Vineyard is not having it.

“This is not your moment baby,” they quip, with a maternal sternness that reminds you why they are one of South Africa’s most revered theytriarchs. The scene could be pulled straight from ’90s Harlem, NYC, but is instead unfolding at a converted warehouse on the outskirts of Cape Town city, bordering the ruins of District Six. The music restarts — a Sho Madjozi bootleg. This is Spectrum, the ball that Vineyard founded. They’re about to deliver one of their infamous ‘teachable moments’ — gesturing towards South Africa’s present relationship with ballroom as both zeitgeist and lingua franca.

Over the past six years, ball culture has ignited a revolution within Cape Town and Johannesburg’s queer underground. Events like Spectrum and the legendary VNJ Ball are evolving the sound of ballroom away from its American lexicon towards something uniquely South African. This new vanguard is not just adopting ball culture — they’re remaking it in their image.

Sure, at your average Spectrum or VNJ, you’ll hear ’90s house bootlegs and Azealia Banks. But woven into and in-between these usual suspects is club music endemic to South Africa. Much like ballroom, these styles are born from disenfranchisement. There’s gqom and kwaito, yaadt music in Cape Town, and the current it-girl of African electronica, amapiano.

“Ball culture post-Covid introduced me to so many young, queer DJs who have been studying the sound, and who have interpreted it in their own language,” says Vineyard. “They’ve taken the historical sonic identity of ballroom and integrated it with their own.” But these DJs are accustomed to playing for dancefloors at club nights. Cape Town’s Yvonne Me is one of them. “It’s a really weird thing, because [at the ball] I’m not playing for the crowd. I’m playing for the people walking the categories,” they say, recognising how their role has to shift. Music functions differently here than it does on a dancefloor.

“It’s the heartbeat,” explains Vineyard. “Ballroom is not just another party. Each category demands its own particular palette, which makes ballroom so rich. You really get to journey through a spectrum of sound.” This was a learning curve for the DJs booked to play Vineyard’s first functions. “Initially, there was a process where I worked very closely with who I’d asked to play my ball,” they recall. “I think that’s what’s so amazing about this whole thing. Because there was no frame of reference, everything that’s developed has kind of just happened on its own.”

Yvonne Me remembers Googling “what is ballroom music?” before deciding, “let me just throw the songs that I really like and a couple of throwbacks into one playlist, because why can’t that be ballroom music?” To them, ballroom is an opportunity to reclaim local sounds the queer community has felt excluded from. “I kind of struggle with the fact that we’re not bringing local house music further into our ballroom culture,” they say. “I feel like there’s this perception that house music is still male-dominated. There’s this wall that’s been built up towards it. It peeves me, because house music sits so deeply in our culture as African people. I’m not setting aside my queerness to engage with it, I’m trying to create a space of acceptance.”

“I find that ballroom’s sound is also a response to pop culture… It’s a response to the sound of the time.” – Cheshire Vineyard, SPECTRUM founder

Ball culture as we know it dates back to 1960s New York, arising as a reaction by Black and Latina drag queens against the inherent racism of white drag pageants. They created a space for queens of colour to embody the “realness” of identities barred from them in reality, such as wealthy businesswomen or Upper Eastside socialites. This also became a space of safety and visibility for the transgender community, otherwise excluded from the drag scene. Rejecting the rules of white pageants, bodies were liberated to move as they pleased, birthing the dance style vogue and its accompanying house music offshoot. But you won’t immediately encounter ‘The HA’ at Spectrum. South African ballroom is cultivating its sound (and community) from what already exists here.

“Things shifted majorly for me when the Kewpie archive was discovered,” Vineyard says, referring to a collection of photographs acquired by the District Six Museum in 2018, documenting a queer community leader from the ’60s and Vineyard’s closest foremother. “Kewpie wasn’t just performing femininity, she wanted to move. And I feel like that is so ballroom. And now we know, when ballroom was emerging in New York, we had Kewpie and the girls living their best life in District Six.”

To establish South Africa’s role in the global ballroom community, the country’s ballroom leaders pioneered a new category — ‘African Realness’. “It’s a category in development, an opportunity to make our contribution to ballroom,” explains Vineyard. “But it’s where amapiano, Afrobeats, and gqom really find themselves in the space.” It’s a happy coincidence that these styles share a staggering number of similarities to ‘traditional’ vogue beats.

Mandy Alexander, a Johannesburg-based DJ and music journalist, has been studying ballroom for some time now. For her, this is no coincidence. “If you go on Angel-Ho’s Bandcamp, the music is there, years before we even had a ballroom scene in South Africa. And I don’t think that Angel-Ho is the only artist.”

Ntsikelelo “Lelo” Meslani, resident DJ and founder of VNJ, identifies mostly with gqom and Afrobeats: “Gqom is one clear example of how a local sound can bring the same energy that vogue beats, baile funk, and Jersey club do in ballrooms around the world.” Alexander concurs, “This is just like my theory on music itself,” she says. “What I play is rooted in Detroit, Chicago and New York, but the substance of it comes from Africa.”

Vineyard identifies these links on a more somatic level. “The iconic MC chants is where there’s this beautiful segue into South African ballroom, because I viscerally understand the connection ballroom has to ancient African cultures, where shamans would spur the movement of the body through the voice. In ballroom, how people move their bodies is kind of radical, liberated.”

To truly liberate bodies, they must first feel comfortable. Alexander understands this, especially in Cape Town where issues of accessibility influence what she spins at a ball. “I’m from Grassy Park, out of the city. It’s not very easy to access the CBD [central business district] if you’re not there or like 10 minutes away. So knowing people hustle to get to the CBD, if I’m DJing the ball, I’m going to set up a space of familiarity, almost like a homecoming.”

Spectrum resident KDOLLAHZ approaches it as a case of knowing “where you come from before you know where you’re going, mos.” The balls allow him to connect with the past. “The beautiful thing about ball culture is that we’re always referencing back to our pioneers and transcestors.” KDOLLAHZ has been described as the “daddy of yaadt music”, a style Vineyard says “any Cape Coloured [person] will recognise as the sound of their childhood”.

Despite its negative connotations in other parts of the world, “Coloured” is the legally recognised term for South Africa’s diverse mixed race population. In the Western Cape, where the majority of this populous resides, they proudly identify as “Cape Coloured” to specify a cultural heritage split between Dutch colonisers, South Asian slaves, and South African indigenous groups. Thus, KDOLLAHZ has been soundtracking Spectrum with music hardwired into a specific local identity. “The vogue style from back in the day, or ‘Old Way’, speaks towards a lot of the ’80s and ’90s pop, house, and R&B that you get in yaadt music — my bread and butter,” he says. Vineyard feels that yaadt music’s presence at Spectrum “ties into this essence of community” by recalling the sound of spaces where communities traditionally come together.

At VNJ, Meslani tries to honour Johannesburg’s hxstory of “thriving scenes in Yeoville, Hillbrow and Soweto”, despite documentation of South Africa’s POC queer scene during apartheid being painfully scarce. “It’s devastating to not have these things in the archive,” says Vineyard, pointing out that we have no way of knowing what Kewpie’s functions sounded like. “And I think that’s our great loss as a generation. We are grieving this erasure that is the consequence of apartheid.” Still, it’s possible to make conjectures based on the evidence.

“Like how American girls name themselves after ateliers and models, Kewpie’s girls named themselves after Hollywood starlets. We can imagine the sound would have been deeply driven by the films that they were watching. I mean jazz was definitely major, too.” Vineyard imagines cultural exchange between underground jazz clubs and Kewpie’s community would have been likely. “There’s this incredible image of a young Miriam Makeba with the girls,” they say. Jazz would also have defined South Africa’s pop landscape at the time. “I find that ballroom’s sound is also a response to pop culture,” Vineyard elaborates. “It’s a response to the sound of the time.”

Using pop as a social tool continues at today’s functions, whether through KDOLLAHZ’s yaadt remixes or the collective joy of celebrating Tyla’s smash-hit, ‘Water’. The most pertinent example, though, is ‘Renaissance’. Since its 2022 release, Beyoncé’s opus has had South African ballrooms under control. The album honours American ball culture and its pioneers, imagining an alternate ballroom outside of our socio-political moment. It does so by fusing house and vogue beats with sounds from the African dance music canon. In essence, ‘Renaissance’ sounds like the dream — exactly what South Africa’s ballroom community has been shaping itself into for the past half-decade.

“America is waking up to those roots we’ve always been aware of,” Vineyard comments. “Like, okay, we’re re-contextualising those roots towards us again.” More pertinent still — ‘Renaissance’ feels less like exploitation and more like homage, in stark contrast to, say, Madonna’s ‘Vogue’. “Beyoncé is crediting girls from the community. She’s including the culture.”

While the growing acknowledgment of ballroom’s contributions to dance music is something Vineyard feels grateful for, there’s a fine line between appreciation and appropriation. “If it doesn’t come back to benefit the community in some way, it’s problematic.” The seminal 1990 documentary, Paris Is Burning, is credited to a cisgender white woman — a ballroom outsider. It’s one example of how ballroom’s aesthetics and narratives have been exploited by those same power structures it rallies against. “Because we have a history of the American ballroom scene being appropriated, I feel like we can navigate it better,” Vineyard says. “With Spectrum’s hyper-visibility and reputation, it can hold people accountable.”

They have a warning for South Africa’s mainstream DJs and promoters, some of whom have already tried capitalising on ballroom as a trend. “You can’t be playing ballroom beats and employing people who’ve never walked the ball to be ‘nogueing’ on your stage. You can’t be doing that. Because everybody knows where it’s at now. If you want to tap into ballroom, come to the source, come to the community. Work with us.”

For South Africa, ballroom isn’t an approximation of American culture — it’s personal. Despite adopting a groundbreakingly pro-LGBTQIA+ constitution at the dawn of its democracy, the struggles facing Kewpie and her community 60 years ago prevail. It’s part of the reason why ballroom has been confined to Cape Town and Johannesburg’s cities for now. “Queer kids still feel this displacement when they’re being ostracised, thrown out, cut off,” Vineyard says. “That’s something that many queer people of colour from the Cape Flats still experience. There’s also a warm embrace of queer bodies there, but there’s still this sense of… outsiderness.”

In fact, one of the country’s original ballroom pioneers, founding mother of The House Of Le Cap Kirvan Fortuin, lost his life at the hands of a hate crime in 2020 alongside several other queer bodies. Two years later, The House of Le Cap would launch The Legacy Ball in their mother’s honour. Ballroom then, like so many of South Africa’s youth-led revolts, is a radical act of defiance.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.