Hostile real estate prices and government policies have the city’s promoters and artists in an existential chokehold. But there’s a new generation of nightlife locals with inventive solutions to combat the lack of space.

The skyrocketing Miami real estate market has left local promoters and club owners in the dust. Following an initial COVID lockdown in 2020, Florida’s controversial Republican governor Ron DeSantis reversed course and reopened the state to anyone and everyone. Over 500,000 new residents moved to Florida in 2021 alone, many attracted by its low taxes, warm climate and lack of regulations on businesses. Miami Mayor Francis Suarez took to Twitter to pitch the city as a budding tech and finance hub with abundant access to Latin American markets, prompting moves from eastern finance firms and Silicon Valley venture capital.

The result has been a property speculation boom that, when combined with the city’s relatively low wages, put many businesses and residents on the street. Asking rents for industrial space, for instance, went up by 53 percent in the last year alone. Nobody can afford to buy, let alone rent, adequate space for a music venue because so much land has been snapped up by outside investors with a predilection for grand, “world-class urban” designs.

“Most of the time [these property owners] are outside players and don’t even live here, or they’re so detached from Miami that they’re just looking for a quick flip,” says Mejía.

The last six months have seen a spate of sudden venue closures. ATV Records, the premier spot for underground dance music in the city, held a month-long goodbye series before shutting down. Las Rosas, a popular punk and metal-focused bar that became a shelter for the scene after their previous haven, Churchill’s Pub, closed during the pandemic, also shuttered suddenly over one summer weekend. Both were important venues for locals thanks to their wide-ranging, genre-agnostic booking policies that included nights for jazz, hip-hop, noise and experimental music.

At the same time, the scene feels diminished as a whole since the pandemic. Prices for everything in the city associated with nightlife, from covers to parking to already-expensive drinks, have gone up. Inflation and a cost of living crisis have also squeezed Miamians uniquely; the city is the most rent-burdened in the country, and housing costs have only risen since the pandemic migration wave. As a result, people are going out less to save more.

“Before, Thursdays, even Wednesdays were always active. I think the scene post-COVID has died down,” says Yepez. In other words, the city’s music and nightlife community is at odds, at ends and struggling to survive.

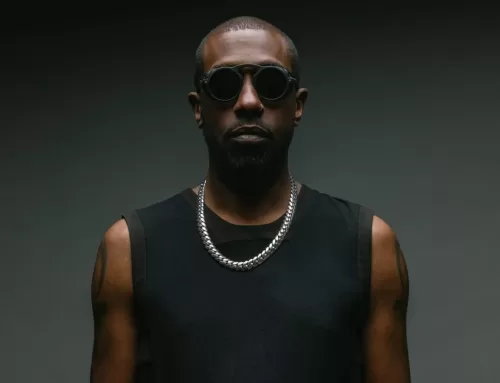

Club Space, located in the Park West nightlife district, is one of the last places in the city that regularly books interesting, boundary-pushing talent.

For two decades, the Park West 24-hour entertainment district where the Hangar once stood was the heart of nightlife in Miami. Since the turn of the millennium, dozens of clubs and live venues have risen and fallen—all within a stone’s throw of Northeast Eleventh Street and North Miami Avenue, a gritty zone of crumbling walls, desolate lots, and glitzy skyscrapers looming above. Today, only two remain. Their survival tells a tale of two cities, one for tourists and wealthy migrants from parts unknown, another for the people that actually live there.

On the north side of the street is E11even. Billing itself as “the world’s only 24/7 ultraclub,” the venue features lavish parties involving bottle service, VIP areas, exotic dancers and appearances by celebrities and famous rappers. It represents everything outsiders associate with Miami—fame, glamour, wealth, extravagance—and everything born-and-bred locals have grown to resent—the exclusivity, the high cost of living and the feeling that everything in the city is for rich fly-ins and nothing is for them.

E11even was founded in 2014 by Dennis DeGori, a nightclub impresario originally from New York. The club’s investors, in the process of building a complete lifestyle brand that includes vodka, a crypto-themed music label and a collection of NFTs, also have a stake in real estate development. They are in the process of constructing a giant luxury condo tower just across the street on top of what used to be the Hangar, to be completed in 2024. Pricing for apartment reportedly started at $300,000, with penthouses listed at $10 million. All units have sold.

Across the street is Club Space, one of the last places in the city that regularly books interesting, boundary-pushing club talent. The club, which locals just call “Space”, was taken over in 2015 by a group of independent promoters fronted by III Points, which runs the eclectic festival of the same name. Under their auspices, a new wave of cutting-edge, left field and Latin-infused techno and psychedelic downtempo has risen, including the likes of Nick León, INVT, Sister System, Bitter Babe, and others.

Yet Space’s management has had to walk a tightrope between satisfying commercial concerns and upholding its reputation within the underground. While big room house and techno acts regularly play through to Sunday morning on the top-floor Terrace, two more adventurous spaces on the lower floors cater to more eclectic tastes: The Ground, a dark, mid-size room, and Floyd, a cocktail lounge with a jazzy, intimate atmosphere.

More recently, however, Floyd and the Ground have become crowded sanctuaries for Miami’s independent promoters, who are dealing with an apocalyptic lack of venue space. Jezebel, one of the most exciting new promoters in the city, was a casualty of ATV Records’ shutdown. Run by Yepez and Mejía, the duo saw a packed turnout for their final event at ATV with a lineup that included New York heavyweight Kush Jones playing back-to-back with DJ Swisha and acclaimed UK junglist Tim Reaper making his Miami debut

Floyd is a cocktail lounge with a jazzy, intimate atmosphere located on the lower floor of Club Space.

“We try to do a lot of debuts here. [There’s] a lot of fresh acts that haven’t come to Miami yet,” says Yepez. “At the same time there’s a risk, because we’re testing out sounds that they’re not accustomed to.”

The duo have had to make compromises to keep going, downgrading from a Saturday monthly at ATV to sporadic Thursday nights at the Ground and teaming up with other promoters to put on events. Other relatively recent arrivals to Space include the perreo and reggaeton party Out of Service and the queer rave Otherworld.

Everyone agrees that things could be better, including Space’s management. Alexis Sosa-Toro, who DJs as Sister System and works for Space as Floyd’s booking coordinator, says that independent parties, the majority of which are run by friends of the club, barely break even, and the club is losing money by even putting them on.

“There are no other spaces for these people to go, and because they exist here there’s a moral obligation to share the resources and the space,” Sosa-Toro says. “But it is difficult, obviously, to bypass the regular audience that comes to Space and still try to have the independent audience feel comfortable.”

One source of discomfort is that Space has access to significantly more capital and real estate than any of the promoters sharing their building. In addition to the club, Space’s ownership began operating two separately-owned outdoor venues during the pandemic: Space Park, a mixed-use space in Little Haiti with a marketplace and food vendors, and Factory Town, a spartan warehouse venue in the far western suburbs of Hialeah.

There’s also an elephant in the room in regards to their relationship with Insomniac, the mega-promoter in charge of the Electric Daisy Carnival festival brand. The Live Nation subsidiary acquired an ownership stake in Club Space in 2019. Sosa-Toro says their involvement in the club is limited to logistics, but their presence has made some uneasy with the dominant position of III Points, an Insomniac-backed project, in Miami nightlife.

“They’re not here, they don’t live here,” says Mejía of Insomniac. “It’s a corporate situation. They’re seeing how profitable it looks from the outside.”

“We call it a necessary evil,” adds Yepez, who nevertheless laments the way commercialism has changed the club. “Space used to be so different…I always go back to this night of Ben UFO back-to-back Four Tet at the Terrace. You’ll never find that again.”

Ground and its neighboring room within Club Space, Floyd, have become crowded sanctuaries for Miami’s independent promoters.

Expenses may be the biggest factor stunting Miami’s nightlife, but another is the city government, which, though nominally run by small-business conservatives, has made the permitting process for businesses next to impossible.

“That’s why everyone does it illegally, because you gotta run back and forth, pay all this, pay all that, you still get denied, you gotta resubmit. Doing things legit is such a pain in the ass and for some people, it’s literally not worth the time and effort,” reports Laszlo Kristaly, one of three partners running the Boombox in South Miami, an off-the-grid warehouse venue with a secret location that was, until recently, run without proper permits.

The city wasn’t always so hostile to nightlife. When it opened in 2000, Space was the first of a wave of venues taking advantage of a revolutionary scheme masterminded by the late Miami-Dade County Commissioner Arthur Teele: the 24-hour entertainment district.

Teele’s commissioner district in the early 2000s included both Park West and the historically Black neighborhood of Overtown. At the turn of the millennium the area was blighted and crime-ridden thanks to years of racist, regressive policy decisions from segregation to redlining. His plan was simple but incredibly effective. He spearheaded a campaign to revitalize the area by granting a limited number of 24-hour liquor licenses to clubs like Space. Dozens of venues rose up on and around 11th Street, including vast, multi-room clubs like Metropolis, live venues like Studio A and Grand Central, and more intimate spots like Vagabond. Sporadic police raids also gave the area a druggy, dangerous reputation, inadvertently raising its allure.

“The barrier of entry to start a club was much lower.” says Jose Duran, longtime associate editor for the Miami New Times. “I think kids were a lot more resourceful. One of the most popular nights in Miami, Poplife, started in a restaurant. The kids would ask a restaurant owner, ‘Hey, can we hold a club night after your restaurant closes?’ And they would just push the tables to the side.”

Duran has been covering nightlife in Miami since the early 2000s, and he recalls a much more fertile, enterprising environment for nightlife during this time. For one, everything was less expensive for all involved, and so the club scenes in Miami Beach and Downtown thrived alongside raves being held further out. There was also more variety in terms of musical offerings, with clubs incorporating rooms for house and techno, hip-hop, Top 40, Latin, and even jungle, all under the same roof.

The scene was also more accessible to less affluent clubgoers. “A lot of club nights would have guest lists that would be open until 11 or midnight. So you had to get there early if you wanted to take advantage of the free entry. A lot of nights would hold open bar from 11 to 12 AM.”

Things started to change with the EDM boom in the early 2010s. DJs began demanding extravagant fees only the largest and wealthiest clubs could afford. “I remember a top-tier DJ was maybe like five to ten grand,” Duran says. “I heard from my friends who were working at Mansion, which was a big nightclub back in the day, they were saying DJs wouldn’t play for less than 100 grand now. That’s a huge jump in fees. And a lot of that had to do with festivals paying DJs more. So the DJs then expected clubs to pay them more.”

A few larger clubs successfully transitioned to the bottle service model that has made the likes of E11even and LIV star magnets. Sosa-Toro says that Space’s survival hinges upon catering to this crowd, and that the local market doesn’t have enough density alone to support it.

“On any given night, more than 50 percent of the people in Space are not locals,” she says, also pointing to the club and city’s draw for Floridians driving down from cities like Orlando and Tampa, in addition to vacationers from outside the state.

As the decade wore on and residential towers and splashy developments began popping up in the clubbing districts, even festivals started to attract the ire of a new class of wealthy condo owners. In 2018, Ultra Music Festival, a bastion of the city’s electronic scene that rode the EDM wave to massive profits, was briefly, infamously exiled from its longtime venue in downtown’s Bayfront Park thanks to lobbying from condo residents. In Park West, the city stopped issuing 24-hour liquor licenses. And in Miami Beach, the local government has aggressively restricted nighttime entertainment, instituting curfews during heavy periods such as spring break and enforcing them with armoured police vehicles. (Some have criticised such measures as overtly racist.)

The fertile environment for nighttime entertainment in Miami has become a thing of the past.

Cano and his friends Laszlo Kristaly and Miguel Cala are all veterans of the Miami DIY scene that matriculated at now-lost venues like Post and Space Mountain. They grew up hearing stories about the ghosts of venues past and opened the Boombox, now in its second and hopefully final location, in order to support Miami’s creative underground. They’re eclectic in terms of programming, and there has been a cross-pollination between different music milieus as a result, like punks intersecting with the rave scene.

The Boombox has two mottos. The first, in their Instagram bio, is “Where Stars Are Born.” The venue’s goal is to be an incubator for local talent, promoters and the wider Miami music community. They point to success stories like producer Coffintexts and DJ Winter Wrong. (“She’s got a Boombox tattoo and it’s for a reason,” Cano says.) Both of them played this year’s III Points festival after their Boombox gigs increased their clout.

Their second motto is “For locals, by locals.” Their goal with the space is to provide Miami’s musicians with a platform, build up its community and bring up local talent. It’s a world away in terms of concept and intention from downtown promoters like the III Points/ Club Space group, who have always preferred to focus on acts from outside of Miami.

“III Points’ intention was to make Miami feel like a really nice place to bring people that don’t usually play here, for then the crowd to see them at an affordable price,” says Cano. “That sentence has nothing to do with the artists that live in this city. Now, obviously, you are putting artists before the big headliner, for exposure. That’s a no-brainer. But then again it’s like, what are you really doing for that scene, for that culture?”

It is exactly this DIY ethos that has allowed the Boombox to succeed just as downtown begins to fade. The venue may be out in the suburban wastelands of la Saguesera (a colloquial Cuban-Spanish expression referring to the “southwest area” of Dade County), but this only means it’s closer and more central to where their fans can afford to live. Their cover and drink prices are also substantially cheaper than that of downtown clubs. As a result, they’ve attracted a crowd of passionate regulars, some willing to drive a few hours to attend. They’ve refused to play the downtown game of fighting over dwindling real estate and have been rewarded for it.

“I feel like they’re trying something new in a vastly different area that has not been known for its nightlife,” says Jose Duran. “These other promoters are still working within the parameters of what the urban core is offering them, and I think a lot has to do with—well shit—they don’t have a lot of other options.”

Plenty of other obstacles remain for nightlife in Miami as it flees beyond the city limits. By all indications, the city will never be the same as it once was. But it will stay alive and kicking as long as someone is willing to make the space.

“I don’t even care if we were making the kind of money to afford prime real estate,” says Kristaly. “We don’t want prime real estate because we’ll turn shit real estate into prime real estate.”

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.