For years, rotary mixers have been status symbols of superior build and sound quality. But is rotary always ‘better’ by default? Or has the cult of the rotary mixer created a monster? Declan McGlynn investigates

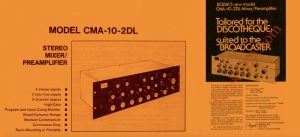

Rotaries were the first DJ mixers. Prototyped by legendary sound engineer Alex Rosner, the CMA-10-2D from Bozak became the first commercially available club mixer — earning the status of being the industry standard by the mid-’70s — followed quickly by the Urei 1620. Unlike today, they weren’t portable and were designed to be rack-mounted in the booth. They also contained very few features, instead focusing on quality and simplicity in their design. The Bozak eventually went on to become the install mixer in legendary NYC clubs like Studio 54, Paradise Garage and The Gallery.

As hip-hop and breakdance culture emerged in the early ’80s, expectations for what a DJ mixer could and should be, began to change. DJs were experimenting with extending drum breaks for MCs and dancers by cutting two versions of the same record back and forth, and the crossfader became the standard solution. Soon, the need for faster mixing, cuts and tricks, as well as increased affordability and portability, led to fader mixers and integrated circuits replacing the discrete-designed rotaries, with brands like Gemini, Vestax and Technics all releasing landmark units throughout the ’90s.

As digital signal processing improved throughout the early ’00s, the Pioneer DJ DJM series became the industry standard, combining convenience, features and cost. Rotaries became relegated to the world of audiophiles and boutique clubs, retaining their expensive and simple form factor, and their reputation for high-quality sound.

Nowadays, often hand-built by small, boutique companies — sometimes even made to order — they’ve become sought-after kit for vinyl lovers and discerning DJs who prefer a slow blend to a slammed-in mix. Given their storied beginnings in the booths of spaces that went on to define clubbing culture, rotaries have become a status symbol for DJs. They’ve also amassed a cult following in the process, one that’s arguably led to its fair share of pretension.

But what is it that makes rotaries so revered? Does replacing a fader with a knob actually make a difference to the sound? Why are rotaries so expensive compared to other mixers? Are rotaries simply a badge of honour for audiophiles? And what does the future hold for rotaries in a fast-paced, dopamine-hit culture? Let’s find out.

To explain how rotaries work and why they might differ from industry-standard alternatives, it’s good to go back to basics. Rotaries, by their nature, tend to contain a much simpler signal path. There are a few reasons for this: the original DJ mixers that occupied those legendary booths were built at a time when audio hardware technology was a lot more straightforward. Simple transistor circuits, discrete components, and transformers made up most audio equipment, with each element of the signal chain carefully chosen so as not to colour the audio and maintain the truest possible output.

The aim was simple: increase the volume of the input to a suitable level for a club setup, while maintaining the integrity of the input itself. There were rarely gain trim knobs, and often basic two-band EQs controlled the shape of the sound. These were more designed to counteract the room acoustics rather than to be tweaked as each track played.

“The origins of rotaries are just a very basic audio mixer,” explains Andy Rigby-Jones, designer of the iconic Allen & Heath Xone:92. A legend of the DJ mixer game, he worked with Richie Hawtin on the PLAYdifferently MODEL1, and with UK company MasterSounds on their Radius range. He now runs his own high-end audio equipment company, Union Audio. “There’s simply not a lot in them. The more you put in a signal path, the worse it will sound, or the more colour it will add.”

“Vinyl sounds gorgeous, and it’s not as accurate as digital, and for much the same reason, analogue electronics still sound nice” — Andy Rigby-Jones, designer of the Allen & Heath Xone:92

As users of analogue studio equipment will know, analogue signal path distortion isn’t always a bad thing. In fact, much classic studio kit is defined by how they harmonically distort inputs, leading to a thickening of the sound as even-order harmonics are introduced when a signal is subtly overdriven. The challenge for DJ mixers is maintaining that purity while offering a natural harmonic distortion that warms the sound without degrading the signal.

“People say analogue sounds rich and warm and it’s basically because you’re adding tiny levels of distortion, which is why with the [Union Audio DJ mixer] Orbit, we introduced a valve stage,” explains Andy Rigby-Jones. Whereas digital’s ultimate goal is often accuracy, analogue’s variables can be what makes it appealing. “Vinyl sounds gorgeous, and it’s not as accurate as digital, and for much the same reason, analogue electronics still sound nice,” adds Rigby-Jones.

Digital mixers, on the other hand, convert the analogue RCA or phono inputs to digital data, process that data through Digital Signal Processing (DSP) algorithms, and convert that processed signal back to analogue, before sending it out to the mixer’s outputs. The quality of components from the analogue to digital converters, to the DSP algorithms used for filters, EQ and FX, all dictate the quality of a mixer’s sound. This diagram from the manual for the Pioneer DJ V10 mixer gives a good idea of the signal flow in a digital mixer, where ADC is analogue-to-digital converter and DAC is digital-to-analogue. It’s clear, too, how much of the heavy lifting DSP does in a digital mixer.

Much like everything digital, over the years quality has gone up and price has come down, meaning the ‘analogue versus digital’ argument is all but moot, bar the most tedious of kitchen afterparties. Now, it largely comes down to taste, rather than tech.

While digital mixers were being phased in as the booth standard through the ’00s, one rotary — the E&S DJR-400 — dominated the boutique market for many years. Its users include Theo Parrish, Floating Points, Kerri Chandler and Gilles Peterson. Its made-to-order nature meant it was hard to acquire, even if you had the funds, with long waiting lists making it more of a boutique home option than a tech-rider regular. In 2016, UK company MasterSounds released the Radius 2, a compact but powerful two-channel rotary.

“When we launched Radius 2 it was truly unique,” explains MasterSounds founder Ryan Shaw. “Instead of having a traditional layout, we had a high pass filter per channel and super simplistic feature set, which at the time divided opinion, but we knew it would, and wanted to offer something we loved and wanted others to experience. The mixer was a true compact powerhouse.” The Radius was designed by Andy Rigby-Jones, though the two have since parted ways. “Andy’s circuit design meant the mixer was a real piece of high-fidelity audio equipment — essentially a wonderful preamplifier for DJing, unreal sound, and a fresh approach to the scene.”

That approach sparked a mini rotary revival. “Looking back, I was in the right place at the right time,” explains Shaw. “[It was] a catalyst [that ensured] DJs experience quality, in terms of design, sound and crucially, service. I’ve seen that market change hugely, with people wanting quality [and moving] away from mass market products — that for me are sterile — to smaller, boutique ones like us, showcasing our passion for what we do.”

AlphaTheta— responsible for the Pioneer DJ brand — also spotted that trend, both in the market and in requests from the DJ community. “Around five years ago we were monitoring the rotary DJ market,” says Rob Anderson, EMEA Product Planning Manager at AlphaTheta. Pioneer DJ had previously launched rotary modification kits for the DJM-800, essentially replacing the fader with a pot, but keeping the signal path intact. Anderson says they were “never very popular”.

When Pioneer DJ released their flagship mixer, the V10, it was largely praised for its sound quality, and they once again looked into adding rotary mod for DJs who prefer the torque and feel of a knob over a fader. “Because there were six faders,” says Anderson, “the rotaries were super cramped so your fingers got caught in between them. We decided to abort that idea and instead develop a rotary from scratch, to fully facilitate what rotary artists actually want.”

“The best sound system I’ve heard recently is DJ Harvey’s club [Klymax Discotheque, Bali]. They didn’t spare a dime, and you can tell the difference when you walk into that room.” — Ron Trent, DJ and producer

The result was AlphaTheta’s euphonia, released earlier this year, it’s a digital-analogue four-channel hybrid that combines a transformer from audio royalty Rupert Neve — which provides that analogue saturation mentioned above — with modern digital FX. The DJ behemoths felt that, despite being digital, the V10 had achieved a high level of audio quality, so the decision was made to make the euphonia a hybrid. “We knew [the euphonia] didn’t necessarily have to be analogue to achieve the quality that was required,” says Anderson. “But there’s always gonna be a user that wants the warmth and harmonic overtones that you only get when you boost sounds in an analogue circuit. So we started looking into how we can combine the two.”

Given the boutique nature of rotaries — and their sometimes elitist user base — AlphaTheta entering the chat may have raised a few eyebrows. Legendary Chicago artist Ron Trent was one of the DJs who consulted with then-Pioneer DJ on the development of the euphonia, and has already experienced that snobbery first-hand. “The first thing those people will do is hate on [the euphonia] until they hear it,” he says. “I was playing in Zurich [and a guy in the club] was saying he’d read all this stuff, and what people were saying [about the euphonia] and blah blah blah, and I realised that they were just hating on it cause they hadn’t heard it. It’s unfortunate that people are like that.”

While Trent started on a Gemini fader mixer, it was his first experiences with rotaries that introduced him to high-quality sound and considered blends. “By the time I got to the rotary, it was all about mixing,” Trent explains. “We mixed back in the day but it was all about tricks, which is what you see with a lot of battle DJs now. When we got the rotary, I found that the mixing and the concentration on detail and sound were most important. That’s when it took over for me.”

Though Trent’s appreciation for great sound is paramount to his approach to DJing and producing, he also acknowledges the cult of rotary can often lead to pretentious takes and snobbery. “We’re in a time when people are hiding behind names and different surface philosophies, thinking that it somehow gives them some kind of power,” he explains. “There was music snobbery when we grew up but we were always open to things. That’s where innovation comes in. [Some people are] busy trying to posture behind ‘cool’, or what ‘cool’ is. Cool is being yourself, the individual.”

Trent says [The Loft founder] David Mancuso’s original philosophy was all about having an open mind. “That’s how this culture got started. If you keep yourself in the corner or behind a certain kinda music, you’re gonna be limited, and it ain’t nobody’s fault than the person doing that to themselves.”

Appreciation of sound is also at the top of Ron Trent’s list. He explains newer music fans don’t have access to great-sounding rooms as they did in the golden era of clubbing: “There aren’t consistent institutions that allow people to, once a week, experience good sound. And it’s been like that for a minute. Their entry point is listening to MP3s on smaller devices, or through TV. They’re not listening to high-end systems.”

Trent believes any music fan, no matter how unacquainted with quality sound systems, will appreciate great sound when they hear it. “The best sound system I’ve heard recently is DJ Harvey’s club [Klymax Discotheque, Bali],” he explains. “They didn’t spare a dime, and you can tell the difference when you walk into that room. I’d wager if you put any passive music fan in Harvey’s room, it’s gonna blow their mind.”

Whether it’s a back-to-basics approach to mixing, a growing appreciation for good sound at a time when it’s harder and harder to find, MasterSounds and others opening up the market for more DJs, or simply the ongoing, inevitable cultural cycle, rotaries are having another heyday.

Whether they’re ‘better’ really comes down to what you need from your mixer, and, crucially, the rest of the signal chain. Rotaries into cheap, bad speakers will sound cheap and bad. Playing a 128kbps MP3 into a rotary will also sound awful. But, by offering such a high ceiling of quality, rotaries can force us to think differently about the whole sonic ecosystem.

Maybe education is key, as Trent explains. “It starts at home, buy a good quality speaker. I was always checking out new stuff [coming up] — it was serious for me. I wanted to find out about what was the next thing, and why it was considered the best. It can be an expensive hobby, but you get out of it what you put into it. If you wanna play with toys, play with toys. Once you hear real sound, you can’t get around it. You don’t want anything else.”

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.