Amapiano has taken over the world, but despite its success, some of the genre’s most influential creators are not getting the rewards they deserve. In the final instalment of our three-part series documenting Amapiano’s Second Wave, Jake Colvin explores how South Africa’s economic conditions and exploitation from established stars are adversely affecting young producers

This article is the third and final in a three-part series about amapiano, explaining how a second wave of younger producers are innovating the sound and developing the culture. The previous article focused on how sounds are shared and developed between South African artists working in difficult circumstances.

DETACHED FROM THE NARRATIVE

“I think ‘UK funky’ was what ‘UK ama’ is, just 10 years ago,” Kooldrink tells me. “You were taking Afro house, which is an African thing, and packaging it to make sense in your locale, which is the UK.” Kooldrink, the producer behind 2019’s ‘Getting Late’, one of the earliest international pop-amapiano hits, has been a vocal critic of the UK’s appropriation of South African music on social media for some time. As far as he’s concerned, British artists have been exploiting South African culture for years.

In Crossover and Collectivity: Why London’s House Underground is Evolving, I described how Black British producers and DJs were creating a hybrid form of amapiano and UK house. Many people in London were calling this “ama” or “UK ama”. The term, and the idea of a UK subgenre distinct from South African amapiano, hasn’t gone down well with everyone, particularly South African artists.

In the late 2000s, London’s soulful and funky house scene gave rise to a short-lived (as the legend goes) subgenre: UK funky. Artists like Apple, Crazy Cousinz and Donae’o meshed the sounds of broken beat, Afro house and tribal house in their UK funky productions, and Lil Silva, Roska and Champion brought a more bassy, grime-influenced palette to the sound.

But as a genre, early UK funky was not too dissimilar to the Afro house and kwaito sounds already emanating from South Africa in the 2000s. In fact, when many people list out “UK funky classics”, they’re likely to include kwaito, Afro and soulful house tracks. DJ Cleo, ‘East Rand Funk’, DJ Kent and Malehloka Hlalele’s ‘Falling’ and DJ Cndo, ‘Terminator’ were all highly influential in the UK funky scene, and for many British people evoke that era of music. Yet they were all produced and popularised in South Africa.

The repackaging of Afro house that Kooldrink describes accords with how London house legend Supa D speaks (with frustration) about the UK funky scene in London in the mid-2000s. “It’s always been a mixture,” Supa D tells me, “since the early Afro house days. But everything was just called ‘funky’ back then!”

Kooldrink sees history repeating itself with amapiano. His exasperation comes from the uneven distribution of money, fame and success in music culture and innovation. “The issue with ‘UK ama’ and how amapiano is being done in the UK by British people, or diaspora kids,” Kooldrink says, “is the actual originators start to get detached from the narrative of the story.”

Jay Music is one of these recent originators, who has influenced the genre with releases like ‘Deep Groove’, and is breaking through into international touring. Jay grew up in Jeffrey’s Bay, a quiet coastal town in Eastern Cape that gets busy during the summertime tourist season. An introverted teenager, he preferred to spend time in his bedroom rather than outside, and FL Studio gave him a reason to.

Jay Music

Jay Music“I feel like the path that I’m on is the right path,” Jay Music says, “especially with my manager right now. He has all the connects. He’s amazing when it comes to networking, so I feel like him coming on my life path was a sign.”

Having a hard-working manager in your corner makes a major difference to the successes of young amapiano producers. Jay Music often works directly with a distributor instead of a label, which is increasingly common in amapiano. “It’s better working independently,” Kiddyondebeat explains. “Labels don’t work with your vision, they work with their vision, so things become difficult… If someone came to ask me,” he says, having thought this through for his own career, “I’d say: ‘do it on your own, bro.² Find a good manager and a team who will focus on you alone.’”

The amapiano era reflects a general trend in international music industries: the shifting role of labels. Music can now be produced and mastered on a laptop, then distributed worldwide through aggregators like DistroKid or distributors like Africori (in which Warner Music Group owns a majority stake). While labels still carry some cultural prestige in South African music, and are needed to give artists a marketing push, their power to gatekeep audiences has diminished. More people have begun to bypass them by releasing directly through aggregators.

“When we talk about access to certain things in music, it means you might have to go through certain individuals,” Golden Lady says. “The great thing about amapiano now is producers don’t need to go through anybody to have access. They can just sit in a backroom, produce, produce, produce, put it out through DistroKid, and their music is up there. And they’ll just wait until they get one song that gets picked up by a record label, or a superstar, and that’s what makes them money.”

Real Nox

Real NoxYoung producers are street-smart about drawing attention to their music. One common tactic is “tributes”. Real Nox released ‘Jingle Bells’, a full EP of tributes to his favourite artists, mimicking their production styles through his own original tracks (‘Rekere to Kabza De Small’, ‘Party with Mr Jazziq x Vinox’ and ‘Jingle Bells to Mellow x Sleazy’). “By adding ‘a tribute to Major League’,” Golden Lady says, “that’s going to come up somewhere through the algorithm as being related to Major League.” Listeners searching for a big-time artist on a streaming platform will suddenly stumble on “some young boy in the middle of nowhere.”

Producers also aim for virality. Some reach out directly to TikTok dancers for a dance challenge for a new song. “That plays a huge role in how big a song is,” Jay Music says. “You can’t just release an amapiano song nowadays, it needs a dance challenge.”

Or they manufacture controversy. JayMea lets me in on a scheme to promote his next release: “I’m going to go on a rant on Instagram about how people stole my laptop,” he explains. “Then on Thursday I’m going to post a snippet of the whole album, and hopefully that will get people tuned into it.”

Photo: Setumo-Thebe Mohlomi

Photo: Setumo-Thebe MohlomiThe most common way amapiano artists try to get noticed, though, is through collaboration. It’s rare to see a popular track that doesn’t feature several artists. Some underground hits are branded as crew productions, with each artist’s picture featured on the cover (see Sizwe Nineteen – ‘Habibi (Quantum Sound) (feat. R-Bee, De’vine 07, Drumonade & Tumi Sdomane)’ and ‘W4DE & TNK MusiQ – France (feat. Philharmonic & Gaziba)’). Self-organised and equitable collaborations provide opportunities for upcoming artists to develop their sound, maintain a constant flow of music, and create album-length projects.

But in many cases, famous artists (including DJs who don’t produce music) simply co-sign the release, particularly on tracks “featuring” multiple artists. While lending their name and brand to an upcoming producer, they may buy-out or claim part or all of the royalties, and use its popularity to boost their touring performances.

This “featuring” system can boost the profiles of upcoming producers, and it’s become a route to success for some. But it also creates the potential for exploitation. The conditions are ripe for more famous artists to capitalise on the talent of township producers. This is compounded by the way international music industries operate, with the most lucrative gigs often found abroad. This puts both artists from South Africa who can travel and South African-influenced artists based elsewhere far ahead of township innovators when it comes to earning potential. “Influential producers from townships in South Africa are still sitting where they are,” Kooldrink explains, “but British producers can do two ‘UK ama’ songs and make more money than those kids will have seen in the last year, from two shows.”

BLACK DIAMONDS AND TOWNSHIP INNOVATORS

Amapiano listeners based in the Global North might struggle to comprehend the extent of the inequalities in South African society. Although townships are often invoked in writing about amapiano, the genre is associated with money and glamour, particularly for international audiences. Major League DJz’s prominent “Balcony Mix” series features the two brothers DJing in luxury settings around the world – on hotel rooftops, by huge swimming pools or flashy homes, with DJs and their entourage dripping in designer clothing.³

If amapiano arises from townships, where so many people are struggling financially, why are these images of luxury and economic success so prominent? To begin to answer this, it’s important to understand South Africa’s “Black diamonds”. The phrase “Black diamond” is used to describe wealthy members of the country’s socially and economically mobile Black middle class. In his book Kwaito’s Promise, Gavin Steingo describes how successful musicians in the kwaito era became Black diamonds, relocating from townships to the suburbs, but remaining closely tied to townships through family, ceremonies and casual visits. As Black-run labels got up and running in the post-apartheid years, middle class Black South Africans coordinated the production of music by people in townships.

In amapiano, established musicians similarly take on an organisational and coordination role with upcoming producers. Some of these musicians may be from a township background themselves, having found success earlier on in amapiano or other genres. Others are already part of South Africa’s middle class through family backgrounds. Many invite younger township artists to produce tracks for them with the intention of presenting them as collaborations or features, something like a mix of ghost-producing and the type of artist curation previously done by label managers. But I was told that in some cases, the already-famous artist doesn’t pay the featured artist/s fairly, or passes the track off as their work, without crediting or properly paying additional producers.

One artist I spoke to (who preferred to stay anonymous) was burned by a very well-known amapiano artist when he didn’t have a contract to say what he’d produced and what percentage he was entitled to. This is a recurring problem. “People promise to put you on, but they don’t want to pay for your beats,” he tells me. “I know a lot of guys with big songs, but they haven’t received any money from them because there’s nothing on paper. You can’t really prove that you were part of this song that has this platinum status.”

Kooldrink tells me that “showboating”, presenting an image of luxury and financial success, is part of the Black diamond lifestyle in South Africa. He accuses certain unscrupulous artists of using this to entice younger, less privileged producers to work with them. “The Black diamond producers have big houses in affluent suburbs like Midrand in Jo’burg. They will go out and find kids, people who are like 17, 18, 19, and they will be like, ‘hey guys, the four of you, I see you guys making music in the township. Come stay with me for a year, come live at my house.’

“These kids are taken out of the township where they’ve never seen the Black diamond life. The artist says, ‘the four of you are going to stay in my mansion, you can have everything you want, people on TikTok will see you rolling around with me and you become the cool guy. And you guys just have to make music.’”

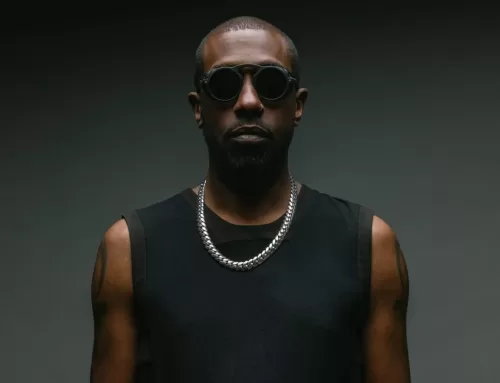

Kooldrink

Kooldrink

Including the upcoming township artists as featured names on the tracks, Kooldrink says, helps mitigate accusations of exploitation. But even when artists are included in official credits and financial splits, they may still end up short-changed by the structure of the electronic music industry.

In 2023, Tyler ICU & Tumelo.za released ‘Mnike’, featuring DJ Maphorisa, Nandipha808, Ceeka RSA and Tyron Dee. The track quickly became one of the year’s amapiano anthems. Tyler ICU found early success collaborating on tracks with DJ Maphorisa like ‘Izolo’ and ‘Banyana’. When ‘Mnike’ dropped, Nandipha808 and Ceeka RSA, two of the featured artists, accused Tyler ICU and DJ Maphorisa of taking all the credit for their song. As alleged proof, they posted an audio clip of an earlier version with only their names on it. It contained one of the song’s most distinctive features – a seriously overdriven log drum.

In a public conversation on Twitter’s Spaces later shared on YouTube, Tyler shot back. He’d invited them to sign a contract to ensure payment for their share of production work, he said. He then accused them of stirring up controversy to promote their next EP. No one was charging Tyler with the type of mansion-based exploitation Kooldrink recounts, and the artists appear to have quashed any disagreements and continued to work with each other. But one of Nandipha808 and Ceeka RSA’s thornier complaints about ‘Mnike’ was that Tyler ICU had profited unfairly from the track with DJ bookings.

Photo: Setumo-Thebe Mohlomi

Photo: Setumo-Thebe MohlomiSince low-royalty streaming has become the dominant consumption model for music, the distribution of money from recorded music and performances has been a problem for music producers worldwide. The problem is intensified exponentially in South Africa, due to the difficulty of obtaining international visas and tough local competition for bookings. The ability to secure a visa and tour in Europe can result in a steady income. Successful Black diamond DJs can scoop up profitable touring performances using their management teams, social networks and their high brand visibility.

“If you look at some of the biggest amapiano songs on Spotify, there will be seven people credited on the song,” Kooldrink explains. “If you go check each of their profiles, you can see some of them aren’t living the life that this song is supposed to be giving them. So yes, as much as they have the streams for the song, they’re not getting the bookings for it. The Black diamond does that.” Some amapiano producers “graduate” from this system, as Kooldrink puts it. “Their brand will become so big that the Black diamond can’t hold them down.” And a few may then enact a similar cycle of exploitation on younger producers coming after them.

Kooldrink describes how promoters from the African diaspora in Europe will book bigger artists who are exploiting young producers in South Africa. “The thing about being from the diaspora is that you can only understand as far as you can see,” Kooldrink explains, hinting at how promoters based in the UK and Europe are blindsided by – or perhaps turning a blind eye to – the inequalities of amapiano’s featuring system.

Some festival promoters in Europe do their research and look into underground artists in South Africa. DJ Papercuts co-runs Ama Fest, which has been operating since 2021. Based in Barcelona, he and his team visit SA as part of their A&R work. The 2024 Ama Fest line-up features a broad variety of South African and SA-influenced artists, including well-known names like Kamo Mphela and Daliwonga, alongside rising stars like LeeMckrazy and Nandipha808, and a House Warming stage of Afro house and amapiano DJs from London. As a DJ and producer, Papercuts is highly invested in underground artists and innovators. But he tells me about the challenges of booking his favourite upcoming South African musicians within the tough financial context of a UK festival.

Photo: Ama Fest

Photo: Ama Fest

“With the underground artists you basically have to take a risk and say, ‘I think this person’s going to have a big summer,’ so then you can justify spending the money for visas. It’s not just the visas, it’s the flights, it’s the travel party.

“There’s only a certain amount of budget, and you have to maximise what you can do with that budget, so you need to get the names the majority of people know, as well as bringing some of the new people you think are going to have a great summer.”

Nicky Summers is a London-based international DJ and artist from a house music background. After first hearing amapiano played by D-Malice in London in 2019, she connected with South African artists like Luzyo Keys (who she worked with on her first single ‘Shaya’), Sfarzo Rtee, Lash T, Cyfred and Zadok on social media. She’s one of several London-based artists who has been working directly with South African artists. Kwamzy features on Nandipha808’s recent release, ‘Jan Fever’; Charisse C and Koek Sista have collaborated with PYY Log Drum King and ZVRI in their project ‘The Ascension’; Moodz features on tracks with D’Athiz and Unknown DJz; Shannen SP highlights various South African artists through her E.B.N.X project and is collaborating with Jay Music; and Scratchclart brought gqom trailblazers Omagoqa to London for their debut UK show at DRMTRK.

Amapiano’s progenitor, kwaito, and the electronic music culture of townships, was sparked by Black South Africans hearing music of possibilities beyond apartheid. It’s a recent history of Black South Africans looking outwards for inspiration, and articulating the sound of promised freedom. “I guess now we’re changing that,” JayMea says, suggesting the routes of influence and inspiration have switched around. “We’re doing it the other way now.” Flows of money, power and exploitation are less likely to change as easily.

No amount of technological advances, such as the ease of circulating samples, distributing music, or using social media to promote it, will fully remedy unequal and unjust economic realities both within South Africa and in its interfaces with international music industries. But gradually, some young artists from amapiano’s second wave are making successful careers out of a genre steeped in kwaito culture and Black South African township experience.

Kiddyondebeat

Kiddyondebeat

Kiddyondebeat is still pleased to see amapiano’s successes: “It’s a sound that originates where most of the community are disadvantaged. It’s really amazing seeing people who grew up with nothing making their dreams come true through music.”

And in the UK, Europe and everywhere beyond South Africa, we can at least try to understand where amapiano really comes from, and realise how complicated inequalities surround every township dream.

Jake Colvin, AKA NKC, is a writer, DJ, producer and founder of the Even The Strong label, follow him on Instagram

² Kiddyondebeat’s use of the word “bro” reflects that the majority of amapiano producers are men. Shiba Melissa Mazaza has done great work to highlight the women of amapiano. Many of the women artists in amapiano are DJs, vocalists and songwriters. My focus on production for this article series meant that most of my interviewees were men. I hope that more balance emerges in the production of amapiano in the future and others are able to fill in any blindspots in my research.

³ Top Dawg Media House is a YouTube mix series channel with a more low-key vibe. It’s a great resource for DJ sets from upcoming South African artists.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.