How DJs Ultra Naté and Lisa Moody helped cement the legacy of house music and Baltimore’s irrevocable connection to the history of the genre.

With a cursory Google search of “house music in Baltimore,” you’ll see several mentions of men like DJ Spen, Karizma, Teddy Douglas, Jay Steinhour, and Thommy Davis, who formed The Basement Boys in 1986.

But an important legacy is often overlooked: that of two Black women who created an itinerant house music party known as Deep Sugar, which has traveled around the city for two decades and shows no signs of slowing down.

Evolving through multiple iterations and more popular than ever because of the renaissance of one of its founders—singer, songwriter, DJ, and producer Ultra Naté, who scored her first major hit with the house classic “Free” in the late ’90s and last year released her 10th album, Ultra—Deep Sugar will celebrate its 20th anniversary next month. With a party, of course.

House music, for those less familiar with the genre, is a kind of fast-paced, typically 120 beats per minute, club-ready electronic dance music with throbbing rhythms, drum machines, synthesizers, and often repetitive vocals. It was pioneered by Black DJs in the post-disco music era and has been incorporated in dance music by major recording artists from Janet Jackson to Lady Gaga. One theory holds that the name “house” itself comes from a 1980s-era Chicago club called The Warehouse.

In 2003, Deep Sugar was started by Naté and promoter and fellow DJ/host Lisa Moody as a happy-hour house music party at the Sonar night club on East Saratoga Street. In the beginning, it was just something between friends, a group that also included Naté’s longtime road manager Jonathan Knox, who wanted to throw parties that they themselves would like to attend, backed by a deep love of music. Six months later, they moved their weekly house music party to Club 1722 on North Charles Street, where they stayed for four-plus years, until they outgrew the venue. Then they spent the next six-and-a-half years partying at The Paradox, the iconic, since-closed, former marble warehouse turned house music and dance club in South Baltimore.

Collectively, Naté and Moody formed what they called “The Sugar Girl Squad.” Catapulted by her international hit “Free”— produced by The Basement Boys in 1998— Naté was already a star, especially in Europe. Moody, who unexpectedly passed away two years ago, established her own identity as well, spinning house classics up and down the East Coast while opening for performers like Grammy-winner Jody Whatley.

Along the way, the duo and their Deep Sugar parties—whatever the venue—helped cement the legacy of house music and Baltimore’s irrevocable connection to the history of the genre.

“There’s been a lot of incarnations of this party,” Naté says looking back, adding that as Black women in a male-dominated field, she and Moody always faced double the scrutiny. “I’ve been the underdog from day one,” she says. “You learn that everything is trial by fire. My whole career has been trial by fire.”

When the Deep Sugar nights first started, Naté, Moody, and Knox would go to events and parties of other genres, bringing fliers, business cards, and branded merchandise. They wanted to spread the word.

“We were so fearless in attempting to grow this thing,” Knox says. “We did guerilla marketing. We would go to parties, we would flier cars.”

“I would legit be on a plane, on the other side of the world in Moscow, on stage for thousands of people,” Naté adds, “And then come home the next day and be flyering a car at a party in Baltimore. And I’m like, ‘What is my life right now? What am I doing?’ I must really love this culture.”

What started out as a small happy-hour music party in 2003 eventually grew into a once-a-week, full-night dance party. Naté and Moody, with Knox’s assistance, proved adept collaborators, soon bringing in chart-topping dance club singer Barbara Tucker to perform for a night at Sonar, which packed the house, but ironically enough led to their move to Club 1722.

“It was amazing,” Naté says of Tucker’s first Deep Sugar show and reception. “But then [Sonar] management expected it to be those great numbers every time at a weekly party. And that didn’t happen. [They] basically pulled the plug three weeks later.”

“I’VE BEEN THE UNDERDOG FROM DAY ONE. YOU LEARN THAT EVERYTHING IS TRIAL BY FIRE.”

“We were homeless,” Knox says, echoing the chorus of Crystal Waters’ popular song “Gypsy Woman” to describe the feelings of the displaced squad. “[But] unbeknownst to myself at that time, the owner of Club 1722 was coming to the Sugar parties when we were having them at Sonar.”

The cozier North Charles Street venue proved a perfect fit because it stayed open after hours for their weekly Friday night dance-a-thons. When they wanted to expand to monthly, much larger parties, the group found a new home at The Paradox, Wayne Davis’ storied 13,000-square-foot night club. (Marking the transition, they also formally changed the party’s name at that point from Sugar to Deep Sugar.)

Davis, also a DJ, once ran the music at O’Dells, one of Baltimore’s most famous night clubs from the mid-’70s to the early ’90s, and he’s considered one of the godfathers of house music in the city. Davis started themed parties around the Baltimore area back in the day, while exploring clubs in New York City like Studio 54, the Loft, and The Garage.

“As a kid, I would have basement parties. I always had this knack for selecting the music,” Davis says. “One of the key things,” he adds of those Big Apple clubs’ success, “was always the great sound. The focus was really on the music.”

When he initially opened The Paradox in 1991, the prevalent music in the club was house music. The club, however, eventually shifted once hip-hop took over and The Paradox’s college night, which mostly played rap music, started to gain momentum. Not surprisingly, the club’s house music night began to dwindle in attendance and in popularity. Nonetheless, when Naté approached Davis about finding a new home for Sugar, he didn’t require much of a sales push. Naté and Moody cared about sound, the texture of the music, the bass, and how its translated across a dance floor as much as Davis did.

“When we talk about where this culture comes from, it is sound-system culture,” Naté adds. “It is built out of analog sound systems, sound systems that you feel, that thunder in your soul, that move you to a certain place. Because those frequencies, those vibrations are different.”

Davis had always been impressed with Naté and believes the size and amenities at The Paradox allowed her to grow the party even further.

“The blueprint and the sound at the club gave her the ability to cash in on those things and expand,” he says. “Because Ultra was in the industry as an entertainer, she already had all these connections, and she was able to bring in bigger names like [New York DJs] David Morales and Louie Vega.”

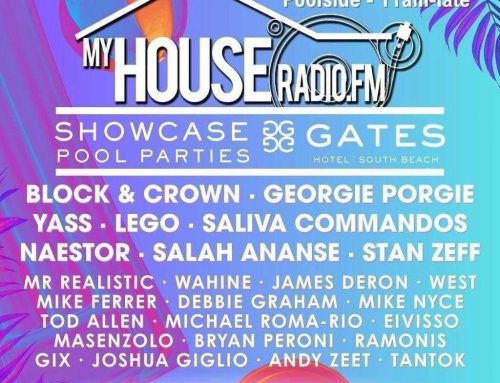

Deep Sugar’s long and successful run at The Paradox lasted until the club closed its doors in 2017. Since the closing of The Paradox, the party has found several other homes. There have been residencies in New York, Florida, in Washington, D.C., and back in Baltimore at Club 1722, at the LB Skybar on the rooftop of the Lord Baltimore Hotel during the summer months, and now at the newly opened Owl Room in D.C.

And even though Lisa Moody is no longer physically present at Deep Sugar events, her impact remains indelible. In June, Deep Sugar’s “Rooftop Jam” at the LB Skybar was dedicated to Moody in celebration and remembrance of her birthday and Naté brought out legendary Philadelphia house music vocalist Lady Alma to sing some of Moody’s favorite songs, including “Let It Fall” and “It’s House Music.” Some came in their Sunday best, some in shorts and sneakers, but all ready to dance.

As Lady Alma sang, those who had known Moody for years embraced and cried. And most of all, as Naté DJ’d throughout the night, everyone—close friends of Moody’s and complete strangers alike—moved to Moody’s favorite beats. If you closed your eyes, you might have felt like you’d been transported to Ibiza, Miami, or Tulum.

“Lisa’s not physically here, but she’s still very much in everything,” Naté says. “Her personality was so big. That girl was a severe piece of work. She was like a dog with a bone, keeping this party going, keeping the energy going, meeting new people, introducing people to the music. She loved seeing people dance. That gave her joy.”

“LISA WAS ABOUT KEEPING THIS PARTY GOING. SHE LOVED SEEING PEOPLE DANCE.”

Davis, now 70, came out of DJ retirement and began spinning records again himself at Deep Sugar events. In fact, he plans on playing at an upcoming Deep Sugar rooftop party on August 13 at Lord Baltimore Hotel. He likes the diversity of the Deep Sugar crowds, adding it’s always one of the parties he looks forward to playing.

“That’s what the scene was all about when I first started as a DJ at places like The Garage,” where, because the focus was on the music, they always attracted all different types of people. “It was a melting pot. Everybody just enjoyed the music, if the music was right and there were no issues.”

In January, Naté’s career took a new turn when she got an unexpected email from 11:11 Media, Paris Hilton’s media company. The company said Hilton had been a fan of her music since she was a teenager and credits the singer’s song “Free” for making an impact on her life. 11:11 Media invited Naté to host a new, 12-part podcast called “The World’s Greatest Nightclubs.”

Launched in June, the podcast explores how different clubs shaped the culture of clubbing, including its origins in the LGBTQ+ community and Black and brown communities that created safe spaces and new dance and music movements around the world.

Meanwhile, next month, Deep Sugar will officially celebrate its 20th anniversary with the Emerald City Ball 3 at Baltimore Soundstage. Naté will headline alongside Jellybean Benitez, one of the original DJs from Studio 54 Evans.

“We never, ever, threw a party just to throw a party,” Knox says, reflecting on Deep Sugar’s two decades. “Our party has always had a mission not only to elevate house music, but also to ensure that we could share that love and bring others into the scene, because we can’t do it forever…the mission was also to reach out and to expand the grasp of house music. To preserve the culture.”

In the true spirit of the underground DIY music scene, Naté knows she has beaten the odds and not only created but sustained something remarkable with Deep Sugar. Marginalized communities will always spur underground scenes and venues. That said, Deep Sugar parties often feel like a family reunion, especially after the pandemic. They’re not exclusive. Quite the contrary. All are welcome—just as long as they come for the music.

“We’ve never made our crowd feel transactional,” Naté says. “We are a culture. We are a family. You are as important as that famous international DJ that might be playing tonight. And I think the biggest part of sustaining [Deep Sugar] is that people do feel that they are valued. You’re welcome to be here. People want you to have a good time and to have done all that we can do within our power for that night to ensure that you have a good time.

“I started out as a little kid just writing a song for fun, and somehow I became a singer-songwriter, as a trade,” Naté continues. “Then fast-forward to suddenly, I became a DJ and a club promoter.”

Within the context of Deep Sugar, she says, evolving it to suit different dance floors hasn’t been difficult for her because she’s always been able to envision how this moveable party can work on a particular occasion, in a particular framework or particular venue.

“At the end of the day,” she says, “the main ingredients are awesome sound, amazing music, and dope-ass people.”

TERI HENDERSON is an arts and culture journalist in Baltimore.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.