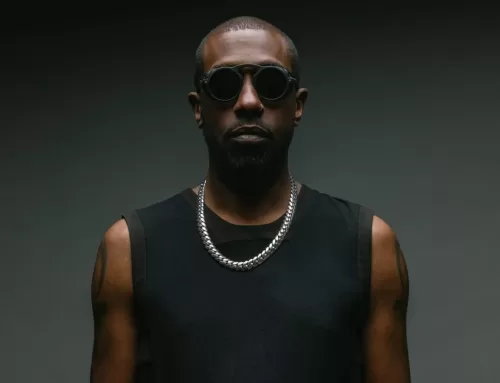

Is there a more complete DJ in our scene? Carlos Hawthorn visited the UK titan at his summer home to unpack one of dance music’s most inspirational careers.

Is there, then, a more complete DJ in our scene? Cox has played pretty much every style of dance music using every type of technology to every type of audience. He played records before it was cool and eventually became the first superstar DJ. He’s done it all: Ibiza residencies, hit records, time-travelling millennium sets. But the really impressive thing is Cox himself, who, as fans or industry bods will tell you, is always the friendliest and most genuine guy in the room. The smile, the energy, the catchphrases—it’s all part of what makes his DJing so infectious.

I sat down with Cox for a long chat in the garden of his sprawling Hove home. With the sea and a cluster of wind turbines in the distance, we discussed his spectacular career in detail, going deep on topics such as three-deck mixing, getting on the mic and the ever-burning desire to stand out from the crowd.

For the best part of 50 years, Carl Cox has been in front of people mixing records, from grafting in pubs and school halls as a teenager to becoming a global brand synonymous with dance music.

You turned 60 in July. It’s kind of incredible to still be doing this.

I think it’s shaken up a lot of people who didn’t realise I was so old, based on my youthfulness I suppose. When I’m out, meeting people, playing, creating… I’m still excited about the future of music. I enjoy it now as much as I ever did.

I read an old interview where someone asked you what you’d be doing in the future. You said producing for up-and-coming artists because “you can’t DJ when you’re 45.”

I can’t believe that interview has come back and bitten me on the arse. When I started the only DJs people knew were radio DJs. People didn’t even know what they looked like. This is the thing about the rave scene: we were the great unknowns.

When I started I was basically a young guy from South London playing at pubs, clubs, scout halls, school discos. A school disco might have 40 people. I started to be known at around 27, 28. I was thinking I’d DJ for another five or six more years and that’d be it. Then I got to 45 and I was like, “nah, I’m not going anywhere soon.”

So what keeps you young?

More than anything I have a young man’s attitude to life, whether it’s my cars, motorbikes, cooking etc. DJing and being out all night isn’t the healthiest of lifestyles, so I’ve had to manage that to be able to still do what I do at my level. For me, it’s the music that prevails. Something that I truly love that gives me a sense of purpose when I wake up in the morning. There’s always something to do.

Are you playing fewer shows now than, say, ten years ago?

I would like to think so! But if you look at my diary it’s chock-a-block. A lot of it is events we put on hold due to the pandemic, as well as new events. This time around I didn’t do Awakenings, Monegros or Tomorrowland, but I did other festivals I haven’t done in a while. I even did Torquay! The English Riviera.

Did the pandemic and its lockdowns give you a desire to get back out there?

No, I was actually thinking of going the other way. After being involved in this for so many years, I took a breath, sat down and re-evaluated where I was at and what I’d like to do next.

Was this at the start of the pandemic?

I was in the middle of quite a big US tour, my first for about ten years. Lots of smaller clubs, no festivals. It was all going really well until I got to Houston, Texas, and played a club called Stereo Live. We were told the situation was really serious and we had to get out of America or risk getting stuck there. I ended up playing for seven hours instead of the usual two or three. Next thing I knew I was at the airport and had to choose to either go to England or Australia. I went with Australia because my setup isn’t bad for a lockdown. I’ve got a decent garden, my studio with all my records. I wouldn’t just be sitting there watching Netflix, eating crisps and putting on more weight.

I was thinking to myself: what can I do? How can I still share my love of music? That’s when I decided to dive back into my vinyl collection and show people where I came from. I took my phone, hit Facebook Live and lo and behold there were thousands of people watching.

You’re talking about the Cabin Fever series.

Yeah. It was a great opportunity to give everyone a history lesson. I sat there, got on the mic and introduced (and back-announced) every record for 90 minutes. All my new fans were like, “Why is he sitting down? Why isn’t he mixing any music?” It blew their minds.

I could’ve just got up and played all the new records like everyone else was doing, but I don’t need to enhance my career at all. Or to be relevant. I’ve been doing that for years. What I haven’t done is show people that this Beastie Boys album was great. Or my love of Trouble Funk and Def Jam Records. It was about exposing people to music in the way that I was exposed to it. I thought the pandemic would last four weeks—we did 52 shows in the end.

You’re right, most artists will have been thinking about how to preserve their careers, whereas you wanted to show people a side to you they may not have known. Plus, on a personal level, watching you mix ’90s rave and trance tunes on vinyl was a trip. Did reconnecting with your record collection have any impact when you eventually returned to touring?

No, not really. For a second I thought about doing vinyl sets on the road, but I would’ve doubled my workload. The idea is very exotic. People want to see records mixed in an expert way.

Who were your favourite vinyl DJs?

Sasha & Digweed were super clean. Seamless. You don’t even hear the transitions. I’m more about “whuuuuuuuup,” just bringing it in.

I was going to say: watching the rave episode, it’s not about perfection. You’re bringing the faders up quickly. You can hear your hands on the records. The whole thing sounds alive.

Yeah I’ve always attacked my mixes, always chased the perfect mix—which doesn’t exist by the way. For me, it’s the art of creation, fusing music together, the power of the blend just coming out. Pure energy. Any DJ can play three records, but I’ll play them and it’ll explode. It’s how I work those tracks together that makes it unique, whether it’s drum & bass, house, techno, whatever. It’s always got that little bit of edge to make it exciting. Every single time I play, the sound technician comes over and thinks I’ve put the levels up. But I haven’t—the way I fuse records together just makes it sound louder. It’s always been the way.

Rave tunes definitely suit that style. I noticed with the trance and techno tunes you keep it a bit neater.

Yeah I calm it down and try to make those transitions as clean as I can. To keep that party rolling.

What are you doing differently?

When you’ve got exciting music, I tend to try and keep the energy up as much as possible. And then I’ll bring it down or take it left or right. I’m not relying on specific records. It’s about how I’m gelling the music together and creating a new experience.

“I was thinking I’d DJ for another five or six more years and that’d be it. Then I got to 45 and I was like, ‘nah, I’m not going anywhere soon.'”

Hearing two or three records in the mix is exciting. Those unique blends are a big part of why people go to see DJs.

Definitely. Every record has a beginning, middle and end. I’m thinking two records ahead all the time, rather than just revelling in whatever’s currently playing. If you enjoy it too much, your next record may fall flat because you haven’t prepared. This is why I’ve got three players—four is too many. You don’t need four.

So you’re rarely not in the mix?

Rarely, yeah. I do sometimes like letting a record do its thing, but then how am I different from the next DJ doing the same thing? If instead I play this record with another one that enhances it, you’ll probably never hear that again. I’ve always thought this way, and I think it’s a big reason why people come back and see me.

Have you ever had favourite transitions? Two tracks that you know work beautifully together. I find it odd it’s not more of a thing.

I don’t get challenged by having two records perfectly in key so they sound like one continuous track. I’ve always been much more about banging two tracks together and riding the groove. But there have been plenty of happy accidents where it was all beautiful and in key.

But you never repeated these mixes?

Not really. The only time was back in 1988—and it’s been well documented over the years—when I was doing this open-air event called Sunrise in Oxfordshire. It was the first summer when I was using three turntables and I had this party trick of mixing two copies of Lil Louis’ “French Kiss” and the a capella version of Doug Lazy’s “Let It Roll.” It was basically a live remix. People had heard both tracks, but not in the way I put them together. I would cut and scratch her moans. People lost their minds.

Let’s talk about vinyl. Take me back to when you were honing your craft in your bedroom, pissing your mum and sister off.

I was 24 or 25.

Oh, wow. So you’d been DJing for a long time.

Absolutely, I was trying to perfect the craft. I was never a natural-born mixer.

So all the gigs at pubs and weddings in your teens and early 20s you were just playing one record after another?

Yeah, I couldn’t afford Technics. It was impossible. I had Citronic decks, very basic.

Were you mixing at all?

Yeah. So I had two Citronic decks, belt-driven, and they were never the same. One was always faster than the other. So I worked out the BPMs on the records and I’d put the faster record on the slower deck and the slower record on the faster deck. Then I’d nudge them and execute a transition mix.

So the decks had pitch faders?

No, I’d use the corner of the platter to slow it down and cut the record in before it sped back up again. I had two copies of Wilton Felder’s “Inherit The Wind,” which I would put on the decks and start together. One would run out before the other, so I would slow it down and then while they were catching back up with each other, you’d get this phasing effect because you were matching them right on top of each other. Phshshshs. It was a lightbulb moment.

I then began experimenting with going between the two records, slowing one down a bit more and cutting between the two, creating a quarter-note delay. I’d do it for hours.

Kind of like beat juggling?

Yeah. I really learnt on the job and just being curious about the art of mixing.

When did you first start beatmatching?

1985 or ’86. But when I was 14 or 15 years old I had these two tape decks—I don’t know when I got these bloody things from—and I’d record lots of music on them. They had variable speed, so you could actually mix, though they weren’t very great.

And of course the hip-hop era was fantastic. As soon as I saw Grandmaster Flash mix up two copies of [Chic’s] “Good Times.”

That was on TV?

On video. Good-Times-Good-Times-Goo-Goo-Goo-Good-Times. I had two copies on Atlantic Records and wore the shit out of them. Another one was Lisa Lisa & Cult Jam’s “I Wonder If I Take You Home.” I cut the shit out of that too. I cut the shit out of everything.

But I was never a turntablist. I enjoyed cutting and scratching—and still do—but I’ve also always been into the rolling DJ. I used hip-hop techniques to elevate my mixes. I used to cut the shit out of the UK breakbeat records. So when the rave scene started, there were a million DJs given an hour each. I had a satchel of vinyl and I’d do three parties a night, playing one-hour sets. I never had a big selection, there was no point. I did that for years and years.

But eventually I felt I was limiting myself by not playing longer, so I stepped up to two hours. This gave me a lot more exposure. A lot of the time people would go home by the time I came on, or arrive too late. But with two hours at least you had a decent window.

So five years in your room practising. Do you start playing clubs after?

I wasn’t old enough in the beginning. I was always a box boy to certain DJs, helping out Paul Oakenfold and Danny Rampling in ’86, ’87, ’88. But then I also had my sound system, which got more work than I did. If you wanted to hire it, I was like, “hey I’m over here.” And I’d go and warm up for them. I had all the latest records, Todd Terry etc.

At this point you’ve left the pubs and weddings behind and you’re trying to make it as a club DJ?

The ’60s were gone. The ’70s I was at school. The ’80s I was still going out, meeting girls, all that sort of stuff. But the ’90s was me. So by the late ’80s, I was perfecting my craft and honing my sound.

Why were you so intent on perfecting your craft first?

It was ’83, ’84 when I first started collecting this music. Back then there was no three-deck mixing because there were only two channels on the mixer. So I had to get another mixer and use it as a preamp to add another turntable. Now I had two mixers and three turntables. What was I going to do?

Then along came Sunrise. My girlfriend and manager at the time, Maxine, said, “go on, do three turntables, you can do it, this is it!” I was like, “what? huh?” It was 10 AM, too. But when I came on… [Rubs hands].

“It was ’83, ’84 when I first started collecting this music. Back then there was no three-deck mixing because there were only two channels on the mixer. So I had to get another mixer and use it as a preamp to add another turntable.”

But you had been practising on three decks before? This wasn’t your first time.

Oh yeah, but it was my first time live.

In front of 15-20,000 people…

Who had no idea who I was at the time.

Did you get nervous?

Yeah, I still do now.

Really?

Yeah, even last night [at The Ned in London] I walked in and everyone was like, “Argggh Carl Cox!!!” And I’m like, “oh my god, I hope it goes well.” Everyone’s expectations are so high. But once I get across the line, one or two records in, I’m in the room.

Because of all the hours spent practising, did you hit the ground running on the club and rave circuit? Were you confident?

I came in forcefully. I knew there were only a handful of people in the world who could spin on three decks. One was Jeff Mills, AKA The Wizard, who I’ve played with many times.

How did you know about him back then?

Just people talking. The sound of Detroit and all that. There was a lot of talk about Jeff and three-deck mixing. Derrick Carter, too, and Donald Glaude in Los Angeles. Ben Sims on more of a techno tip. But for me, it was just something I knew I could do really well at every event.

So let’s break it down. It was a way for you to stand out from your peers. It became your USP. It was on the flyers.

It was all about thinking ahead. I always had three or four records out to choose from, to guide where I was going next. It was a juggling act, the sleeves and records would be everywhere. There were a lot of cuts and a lot of fast, instinctual decisions. And whatever wow moments happened, happened in real time. It was pure improvisation.

How did you make sure the mix wasn’t too cluttered?

You’ve got to let everything breathe. Three decks was my limit because two records can sound pretty great together. But when a third one comes in, one of the other two has to come out.

So you weren’t often playing all three at once?

No, but I would mix in between all three. It was deck juggling. I liked the experimental side of it too. Moving between electro, slowed-down breakbeats, classics. Trying to fuse all this stuff together was a lot of fun. Not everything worked but most of the time it did. I just had a feel for it.

I guess you’re so busy that you’re automatically in the zone. This creates a certain energy, which transmits to the rest of the party.

If you look at videos of me playing on three decks, most of the time I’m not even smiling. I wanted to create. I wanted to give people so much more than just a hit record and some arm waving. The creation was the art. This has been lost a bit today because everything is now on the computer. Everything is in its key range, you can loop on the fly, you can see when the breakdown is. There’s so much you can do now, which makes it a lot easier.

I still like to work, which is why I don’t sync any of my music. I used sync a bit while I had Traktor, because I was using four decks and you had to sync. But it was so linear. All the beats landed really nicely. But was I challenging myself? No.

Staying with your early DJ days, were you conscious of having to play big records?

I’ve always loved big records, and I’ve made a lot of tracks big myself. I’m synonymous with a lot of anthems because I’ve always worked them. But I’ve mixed them in with stuff that no one else has, partly to maximise the crescendos.

How were you getting your hands on such exclusive vinyl?

People knew I had a different ear to everyone else, so they left those records under the counter.

How was your ear different?

I was into a very underground sound. I liked tunes that people probably wouldn’t play. Records that others missed. Then I’d play them and people would be like, “oh what’s this one?” “It’s the one you didn’t want!”

This led to you creating your own sound, a mix of breakbeats and four-on-the-floor. I feel like your career has always been about how you can stand out from the crowd.

For a period, the rave scene was all about breaks, but I loved techno. Not many people played techno—they said it didn’t have enough funk. So the only way to introduce people to techno was to combine it with breakbeats. Then people knew Carl Cox was on.

Weren’t these tunes wildly different tempos?

Yeah I had to do a lot of manipulation, speeding up the techno and slowing down the breakbeats. Again, it’s the art of DJing. Techno didn’t really have samples back then and the breakbeat tunes had loads, so they went really well together. When people heard the stomp, stomp, stomp coming through the breakbeat, it gave everyone a lift.

At what point does Carl Cox become a showman? Was this always in you?

I was a clubber before I was a DJ, so whenever I heard music I was moving. I could never just stand there. I wanted to be dancing as hard as the crowd—I didn’t want to miss out. It’s just natural for me. And when people see me getting down, people have to move.

I’ve always thought there should be an element of showmanship. I’m an entertainer. A lot of DJs will say they’re not but they are. People pay money to come and see you, to be entertained. A friend of mine recently told me about a DJ they went to see in Los Angeles who spent 90 percent of the gig with his back to the audience, just drinking with his mates. I was quite disgusted by it. He’s playing records but not interacting with the crowd at all. He’s more interested in getting phone numbers and cigarettes. I can’t do that. I’m involved.

That’s interesting because I’ve noticed you like to be alone in the booth.

Yeah I do. I don’t need people to vibe me up. I make my own party.

“The story with ‘Oh yes, oh yes’ stems from my love of comedy. I just thought it worked for any audience, in any part of the world. Comedians always say it’s about comic timing, how you deliver the punchline.”

We have to mention you and the mic, all your beloved catchphrases. When did this start?

Because I’m from the old school I’ve always wanted to know if people were having a good time. From the very beginning at the pubs and scout halls—although I was quite shy back then—I wanted people to know there was a human behind all the technology.

The story with “Oh yes, oh yes” stems from my love of comedy. I probably started it around 2000 or 2001. I just thought it worked for any audience, in any part of the world. Comedians always say it’s about comic timing, how you deliver the punchline. “Oh yes, oh yes” is a punchline I unleash just before a big drop. That’s its power.

It’s funny, three years after I started saying it, I decided to stop as an experiment. People were like, “is he OK? Is he sick? We want to hear him say it!” That stuck with me.

So you were on the mic throughout the rave years?

Yeah but there were always MCs in the rave scene, chatting all over your tunes and your mixes. It used to drive me mental, so I scrubbed them. But then who’s gonna MC? Me. I started introducing myself and chatting every now and then, when it suited my sets.

How did things change for you when you switched from vinyl to CD?

I tried for it not to change me, but to enhance. The ability to loop, cut, resample, spinback etc. was so creative. With vinyl you could only do so much. I felt like it was the next step after using three decks. But at first I was resistant. When the [Pioneer DJ] CDJ-1000 landed, I had no desire to use it. It was always there, lurking at the parties I was playing. I remember playing with Kevin Saunderson in Detroit and he was using them. He showed me the loop function and I couldn’t believe it. I loved it: no feedback, no skipping needles. It was a revelation.

Did you then spend a period really getting to know the CDJs?

I had no choice. The CDJ-1000 looks a bit archaic now but at the time it was like something from Mars. Being able to download a track and ten minutes later be looking at the waveform on your player. Genius. It felt like the future.

Did you struggle at all with having too much music? Too much choice?

No. I was pretty strict with myself. If I was doing a two-hour set, I would take four hours of music. It limited the confusion. That’s what I’ve always done, even up until today.

What’s your current DJ setup?

Three Pioneer DJ CDJ-3000s, the latest Pioneer DJM-V10 and the Pioneer DJ DJS-1000, which is a little sampler. I plug a memory stick into that with all my sounds, loops, samples and ideas. Three CDJs for DJing and the DJS-1000 allows me to play my own productions. A lot of my latest album, Electronic Generations, is on there.

Why this mixer?

It’s a game changer. It sounds great and it’s quite big, which is useful because I’ve got big hands. I need space. The buttons on the Allen & Heath are too small. You can also have two lots of FX, which come up on send and return on each channel. Two microphone inputs with bass and treble for tuning your voice. But the one feature that makes it stand out is you can record every single channel into Ableton and separate it into stems. I use this for producing, not DJing. So many things happen while I’m DJing, everything gets recorded and then I revisit it later.

Where does the DJS-1000 come in?

There’s a track on each button and then each track is separated into all the individual stems, which I can manipulate. This syncs to one of the CDJs. I don’t love using it because I don’t sync, but I have no choice. The other two players aren’t synced. So when I want to use the sampler, I sync the third CDJ and then un-sync it when I’m back mixing records.

So you’re playing a lot of your own music in your DJ sets?

Yeah I was making so much music during the pandemic, largely because I could record all the live jams straight from the mixer.

It’s amazing to be 60 and have a whole new project to lose yourself in.

Yeah! I wasn’t expecting it. I had made my last album as far as I was concerned. That came out in 2011. But the pandemic changed everything. Suddenly I’m sitting in my studio with loads of time—and the DJM-V10. It allowed me to do something I’ve always wanted to do: play live.

What is the live setup?

Ableton Live, which has all my tracks, sounds, rhythms on it. This goes through Ableton Push and then out of there I daisy chain all the modules, including a Moog Subharmonicon, a Korg Monologue and the Roland TB-3. I also put some of the modules through Moog pedals and completely manipulate the sound. Noise madness.

You debuted this project at London’s OVO Arena Wembley last autumn, headlining the venue for the first time. After all these years, the fact you’re still outdoing yourself speaks to a thought I had during my research for this piece, which is that I can’t think of a more complete performer in our scene. You’ve experienced every scenario, played every style of music. When I told two of my colleagues who I was interviewing, one of them said she took her first pill to you in Ibiza and the other said you were her first clubbing experience in Brighton. Thousands of people all over the world have stories like this. How do you comprehend the impact you’ve had?

It’s probably one of the hardest questions I’ve had to answer. I still pinch myself. All I know is I’ve worked really hard and always felt a deep passion for listening to music and sharing it with other people. And for having fun. I’m just me, there’s no facade. When I started taking DJing seriously, people asked me what I wanted to call myself. Dave Doubledecks? The Jack Of All Decks? No, Carl Cox. That’s who I am.

As you said, I can more or less go anywhere in the world and someone will have a story. I was on a train to Paris once and a lady was sitting nearby reading a newspaper. She looked up and said, “Hello, I know who you are.” I was like, “Really?” She said, “Yes my son really likes your music. I just want to thank you for making him happy.”

This is it. For me, hard work aside, what underpins your success is actually something very simple: a childlike love of music. You must feel very blessed to have had that burning inside you this whole time.

I do. I’ve never had a plan. A lot of DJs with a plan are always striving for more, when actually they’ve already got more, they’ve got it all. Always striving for number one is a stressful place to be. I never wanted that. All the accolades are great, but it’s always just been about being who I am.

Last summer at Ultra Music Festival in Miami, they played a video to celebrate my 20th anniversary of playing there. All these DJs were talking about me and I welled up, I was crying. Blimey, I’ve done all that? For so many people? And that’s how they see me? I was overwhelmed.

When will you know enough is enough?

To be honest, there’s been a few times I’ve considered it. I’m trying to balance things a bit more now, but I still want to make music and perform. I still want to give people the best time. I still feel like I have a purpose. I’m not a techno grandad yet.

“I still pinch myself. All I know is I’ve worked really hard and always felt a deep passion for listening to music and sharing it with other people. And for having fun. I’m just me, there’s no facade.”

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.