Chicago’s Trax Records released some of the most influential records in house history, but decades later, many of the artists behind them are still waiting to be paid. Harold Heath investigates the long and complicated history of one of house music’s most infamous labels

The Trax Records saga is a tangled tale of pioneering, seminal music created by a clutch of hungry young producers and DJs, whose raw, innovative productions were some of the first house records ever created. Records that would prove to be both influential and popular far beyond their intended audience of Chicago. It’s also a story of dubious business practices, missing royalties, dodgy contracts and lengthy litigation, defined by competing ‘truths’ that are interwoven with house music folklore. It’s gone on so long that some of the players’ stories have had time to undergo a full Game Of Thrones multi-season narrative arc, potentially mutating from villain to hero.

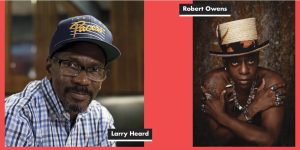

Chicago house publication 5 Magazine has covered the many ins and outs of the Trax saga over the years, providing a voice to several Chicago house artists on the subject, and in 2020 broke the story that Larry Heard and Robert Owens were suing the label. 5 Mag managing editor Terry Matthew sums up the Trax Records story thus: “If you took the aftermath of Factory Records, removed all of the humour and self-deprecation and replaced it with a lot of malice, you’d have something like Trax.”

Mid-‘80s Chicago: the birth date and place of house music, an underground music scene that became a global phenomenon, gave birth to the UK’s acid house and rave revolution, and was the template for clubs, sub-genres and dance music communities around the world. The modern offspring of Chicago house even includes the most commercial, glitter-cannon-wielding, stadium-EDM DJs. No matter how far they may have strayed from the original sound, feel, values and culture of mid-‘80s Chicago house, all DJs owe a debt to that scene: it’s where they came from. Even the name itself — house music — comes from the Warehouse club in Chicago.

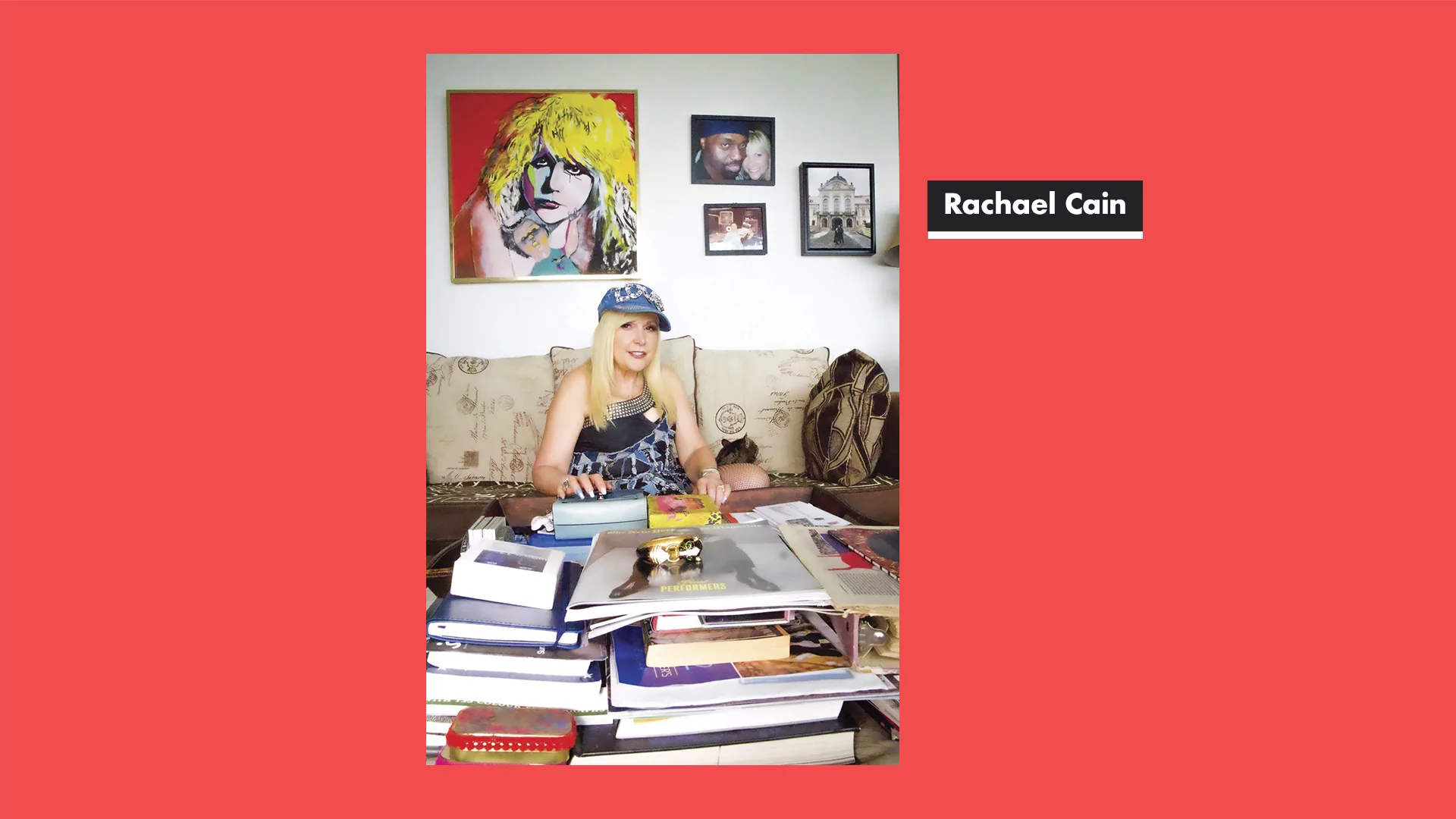

Trax Records and DJ International were the two main Chicago record labels that first spread house music outside of the city to a world which turned out to be wildly more enthusiastic about it than its creators ever imagined. The late ‘80s output of Trax is the history of the development of house music told in vinyl. The initial Trax releases starting in 1985 were raw, exciting, primitive even, sometimes little more than extended rhythm tracks with added sound effects. Current Trax President and co- owner ‘Screamin’’ Rachael Cain’s long association with the label began in ‘85 with her 808-heavy ‘My Main Man’ release; we’ll be hearing more from Cain later.

The following year, Trax Records entered a brief but remarkable period in its history, putting out a series of seminal, era-defining tracks. Aside from releases by Sleezy D, Virgo (Vince Lawrence), Ron Hardy, Master C&J and Sweet D, Trax’s 1987 output included ‘No Way Back’ from Adonis, Marshall Jefferson’s ‘Move Your Body (The House Music Anthem)’, Mr Fingers’ ‘Washing Machine’ / ‘Can You Feel It’ and Frankie Knuckles’ and Jamie Principle’s ‘Baby Wants To Ride’. All hugely important, seminal house music releases. And then if that wasn’t enough, for an encore they casually dropped Phuture’s hugely influential ‘Acid Tracks’ the following year.

We’re so used to the early Chicago house music canon that it’s easy to take these records for granted. Re-listen to ‘Can You Feel It’ from ’86 and try to imagine a world where no artist had ever put these particular musical and rhythmic elements together in this way before: it’s the sound of deep house being invented, on wax. Or for that matter, imagine the impact of the synthetic squelches and raw kick drum of ‘Acid Trax’ if you’d literally never heard anything like it before. This is seismic stuff, crucial moments in popular music history. And Trax was central in disseminating this revolutionary culture to the rest of the world, giving some of the Chicago artists a profile that helped kick-start their careers and creating many opportunities.

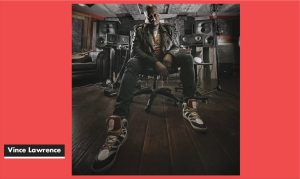

But Trax Records was also haunted by controversy from the very beginning. The label was founded by… and right there, at the very start of the story, is where we hit a problem. The Trax Wikipedia page clearly states that Larry Sherman, who died in 2020, was sole founder in 1984, but producer and Chicago house music innovator Vince Lawrence claims he co-founded the label. Indeed, the number of words on the Wikipedia page dedicated to ensuring readers understand that Lawrence and fellow Chicago house innovator Jesse Saunders didn’t found Trax suggests that Trax lawyers have made substantial contributions to it.

It’s more usually reported that Sherman founded Trax with Lawrence and Jesse Saunders, the word ‘with’ handily obscuring exactly what roles Lawrence and Saunders played. It’s murkiness like this that characterises much about the story of the label, and which has led to many of the creators of these key house records claiming that they were never paid or were knowingly underpaid for their work.

At the heart of the Trax Records story was white Vietnam veteran Larry Sherman. In 1983, Sherman bought Chicago’s only (at the time) vinyl pressing plant and ‘with’ Vince Lawrence and Jesse Saunders launched Trax in 1984. As head of Trax, Sherman was responsible for the distribution of some of house music’s founding tracks, and therefore for creating many new opportunities for several of the early Chicago house artists. But he also had a reputation for exploiting the artists whose records he pressed.

According to Bill Brewster and Frank Broughton’s authoritative Last Night A DJ Saved My Life book, Sherman “wasn’t averse to making some more copies that you didn’t know about and selling them himself”, and over the years many Chicago house artists have claimed that they were treated unfairly by Sherman and Trax. Marshall Jefferson famously tells the story of how his ‘Move Your Body’ mysteriously changed labels from his ‘Other’ label to Trax while at Sherman’s pressing plant. Author Simon Reynolds, in his book Generation Ecstasy, neatly summed up the complexities of Larry Sherman: “Some regard him as a visionary entrepreneur who fostered the scene and provided work for the musicians in the day-to-day operations of Trax. Others accuse Sherman of pursuing short-term profit and neglecting the long-term career prospects of their artists, thereby contributing to the premature demise of the Chicago scene in the late eighties.”

“It wasn’t chaotic. Larry just took everything. He said he’d distribute my records, distribute my label and he took everything… I mean, it wasn’t complicated. He just took all the money” – Marshall Jefferson

Vince Lawrence began his music career back in mid-‘80s Chicago. With Jesse Saunders, he co-wrote what is generally considered the first house record, ‘On And On’, and co-wrote Farley Jackmaster Funk and Saunders’ ‘Love Can’t Turn Around’ too. He later founded his Slang Music Group and went on to remix artists including Beyoncé, Whitney Houston and Michael Jackson.

Over the course of a lengthy phone conversation, Lawrence tells DJ Mag his Trax Records story, beginning with how he and Sherman began working together: “The conversation started something like, ‘Larry, I have songs that we can put out that we could sell. But we don’t have the money for the pressings. So if you front us the pressings, we’ll bring you back the money’. And Larry said, ‘Well, how do I tell the records that I’ve pressed for you as a customer apart from the records that I’m fronting?’ And I said, ‘Let’s start a label just for the stuff you’re fronting. We’ll call it Trax’.” And as simply as that, Trax Records was born.

Marshall Jefferson’s introduction to the Chicago record industry was similarly straightforward. “I saw the address on a record label,” he tells us by phone, “And I just went down there. Vince was there running everything and I just said, ‘Hey, I want to press up records and be a star’. He said, ‘Okay!’” If that all sounds informal, casual, chaotic even, that’s because it often was. The Chicago underground music scene of the mid-‘80s was, as memorably described in Last Night…, a place where “in the furious competition of the time, and in common with the lower-level music business in any city, accounting was rare, royalties rarer, copying and bootlegging were rife, and ownership of tracks was shaky.”

Jefferson has a slightly different take on it though: “It wasn’t chaotic,” he says plaintively. “Larry just took everything. He said he’d distribute my records, distribute my label and he took everything… I mean, it wasn’t complicated. He just took all the money.”

It’s an opinion that chimes with DJ Pierre’s take on Sherman. As one-third of Phuture, he — along with his compatriots Earl ‘Spanky’ Smith and Herbert ‘Herb J’ Jackson — released their seminal ‘Acid Tracks’ on Trax Records in 1987. “Larry was just a ruthless businessman,” Pierre tells DJ Mag via a Zoom interview. “You know, he saw something that he could exploit — and he did.”

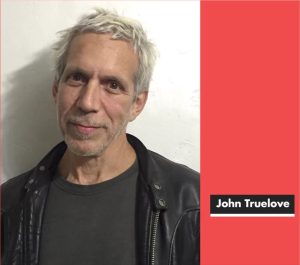

UK music industry professional John Truelove (the man behind The Source’s ‘You Got The Love’) represents publishing company TaP Music, who recently assisted Larry Heard and Robert Owens in successfully suing Trax Records to win back the rights to their music. Truelove tells DJ Mag: “He [Sherman] owned a record pressing plant and realised that he could set up a label to exploit all the (at that time) crazy new music that people like Larry Heard were bringing to him to get pressed up. He must have got a recording and publishing agreement from somewhere and used it without having a clue (nor probably caring) about its implications and how poorly it rewarded the artists.”

Vince Lawrence doesn’t recall signing any contracts at all: “I never signed over anything. I never signed anything. I didn’t have to — I started the label. And it was run like a lemonade stand… I created the name, I designed the logo and I never signed that over either.”

The detail of Heard and Owens’ successful civil action also paints a picture not just of sloppy bookkeeping but of something more deliberate: “…over its more than 30-year history of business operations, Sherman, and then Cain and Trax Records, Inc., built their music catalogue by taking advantage of the unsophisticated but creative house music artists and songwriters by having them sign away their copyrights to their musical works for paltry amounts of money up front and promises of continued royalties throughout the life of the copyrights.”

With ‘Love Can’t Turn Around’ going top 10 in the UK in late ’86 and Steve ‘Silk’ Hurley’s ‘Jack Your Body’ getting to No.1 at the start of ’87, Chicago house suddenly achieved the kind of massive international success that both Sherman and the house originators simply never envisaged: and Sherman clearly took advantage of the situation. “When the acid house explosion took hold in the UK in 1988,” John Truelove tells us, “and everyone became a DJ or simply wanted to hear the tunes that had blown their minds the previous night, he ended up shipping monstrous amounts of 12” vinyl across the Atlantic.”

Readers who’ve ever had their productions signed to a label will likely remember exactly what it’s like when you sign your first deal. It’s a music industry reality, as true in mid-‘80s Chicago as it is today, that when they’re focused on getting their music out there, the vast majority of young producers will just be happy to get their music released and will give little thought to contracts. As Lawrence tells us: “I was 17, man — I just wanted to get records out!”

The potential for huge profits from house music’s early success, together with the haphazard nature of the Chicago house music record industry of the time, left young, naive artists wide open to exploitation. Sherman famously responded to accusations about his business practices way back in a 1997 interview in the Chicago Tribune, saying: “The kids making these records didn’t know what they should get, and they often didn’t know what their material was worth. And being a good businessman, you don’t say, ‘I think you’re underestimating the worth of your material. Here’s a few thousand dollars more’. They’d sign away the rights to a song for a few hundred dollars.”

“I want the company to pay the classic artists royalties and do the right thing, and now that we can finally do that all I want is a chance.” – Rachael Cain

Trax’s revolutionary period came to an abrupt end in 1991 when it went bankrupt, and the label has since been through a complex and confusing journey of litigation and ownership. A relaunched Trax continued to re-package and re-release Trax classics throughout the late ‘90s and 2000s, but the label formed a joint business venture which eventually resulted in ownership of the classic Trax catalogue going to Canadian company Casablanca in 2006. Trax attorney Valerie Baxendale tells us: “Casablanca entered into a License Agreement with a third-party (TRAX RECORDS is under a current NDA with that third-party) whereby that third-party retained all revenues earned from the TRAX catalogue until December 2021. Accordingly, Rachael Cain just recently assumed the role of TRAX RECORDS Principal in January 2022.”

Baxendale is of course referring to the current president of Trax Records, Larry Sherman’s ex-wife, the self-styled ‘Queen of House’, ‘Screamin’’ Rachael Cain. “When we lost control and ownership of the classics completely in 2006,” Cain tells DJ Mag in a written interview, “I stayed and fought for all those years. If it was not for Rick Darke and lawyers for the Creative Arts pro-bono work, all those recordings would not be in America let alone Chicago. Most importantly I formed a new company and have operated under my trademark ‘TRAX Records’ for about 17 years.”

Trax’s Wikipedia page says that Sherman and Cain divorced in 2007 with Cain receiving 50% of the existing Trax library, then when he died in April 2020, Cain received half of the label, with the other half going to Sherman’s other wife. John Truelove tells DJ Mag that he believes that when Sherman and Cain separated in 2007, Cain registered her half share of the publishing catalogue: “The income from that for Rachael should have been substantial. The income over the years to Trax (or their Sanlar Music entity) would have been significantly greater. My understanding is they have always controlled the catalogue themselves. Either because the contracts were buyouts, or because, as claimed by many of their artists, they simply failed to account, it seems extremely likely that the vast majority of publishing income would have ended up in their pockets.”

The ownership of the catalogue is complicated, particularly when you take into account the fact that many artists claim that the label never had the right to licence or sell their compositions in the first place. Vince Lawrence asks: “How do you buy a catalogue when the people who you’re buying it from don’t own the shit?”

Over the years there have been various unsuccessful attempts to take Trax to court by artists who claimed their music was released, re-released or remixed without their consent, their copyright was infringed and they were not fairly compensated. But both Lawrence and Jefferson recall lawyers telling them there was no money to be had from Trax, so there was no point in pursuing the case. “Well, Larry Sherman was always good at hiding his assets,” Jefferson says, “so lawyers would see that he had no money in the bank and they would drop the case… it wasn’t worth their while unless the artists like me would pay, and we couldn’t afford to pay them because Larry Sherman hadn’t paid us.”

This resulted in a legal stalemate for years, but in 2022 things changed. As mentioned previously, last year Larry Heard and Robert Owens successfully sued Trax Records for copyright and won back the rights to their music. The court documents presented by their lawyer stated that when registering copyright for their works, the label, “also inserted knowingly false [our emphasis] information… indicating Trax Records was claiming to be the copyright owner of both the sound recording and the underlying musical composition” and “indicating that Trax Records had received a written copyright assignment from Heard and/or Owens for the copyrights for both the sound recording and the underlying musical composition embodied in the phonorecord.”

In the simplest of layman’s terms, this means the label claimed that they owned music that they didn’t own in order to profit from it. John Truelove tells DJ Mag: “As is often the case with such legendary entities, they find a golden egg lands in their lap and successfully exploit it for all it’s worth without really understanding or caring about the artists behind the work.”

Truelove adds that the settlement in favour of Heard and Owens ensures “that recent and future income for classics such as ‘Can You Feel It’ goes into their pockets.” However, there was no big payout for Heard and Owens, and the Guardian newspaper reported that Heard’s lawyer Robert S. Meloni confirmed that Cain and Trax were unable to pay financial damages. Nevertheless, now Vince Lawrence has gathered together several Chicago house producers and artists including Johnny Fiasco, Jamie Principle, Ralphi Rosario, Jesse Saunders and Marshall Jefferson to sue Trax, the estate of its co-founder Larry Sherman and current owners Rachael Cain and Sandyee Barns, AKA Sandyee Sherman, for copyright infringement.

“This case is important for music in general,” Jefferson tells DJ Mag. “Some of the smaller labels and independent record companies think they can get away with anything, because they assume poor Black kids will never be able to sue them. That’s been the case with Trax. So they just say, ‘Hey, we can do whatever we want and you will never sue us because you can’t afford it’.”

Lawrence and Marshall are both fatalistic about the likelihood of receiving back royalties for their work. “Nobody’s expecting any money because Trax Records doesn’t have any money,” says Jefferson ruefully. The aim at the moment seems to be to mimic the Heard and Owens outcome, where ownership of the song rights revert to the original artists enabling them to claim royalties going forward. According to Rolling Stone magazine, the plaintiffs “allege in court documents and in interviews that Trax didn’t make royalty payments, and in a number of cases released their music without paying them anything at all”, and reported that “The plaintiff’s attorney, Sean Mulroney, refers to the early years of Trax as a “shell game” that included forged signatures, bounced checks, and sketchy (or nonexistent) accounting.”

Again, this is a picture that is echoed by the allegations in Heard and Owens’ successful copyright action, which stated: “…these two artists were not properly compensated for the great value of their musical labors. Instead, the Defendants enriched themselves and brazenly exploited those musical works for their sole benefit, while encouraging, enabling, and aiding and abetting others to do so as well.”

However, Cain claims that the plaintiffs weren’t the only victims in the Trax story. “I’m an artist myself and I also lost all my music,” she said. “I know I never got paid. I can’t say for sure about the other artists.” And in response to the allegations made by Lawrence et al, Trax attorney Baxendale tells DJ Mag that the plaintiffs “have engaged in an egregious pattern of disseminating misleading and slanderous statements both in the media and in court documents”. Clearly, there’s still substantial disagreement between both parties.

With specific regard to royalties, Cain tells DJ Mag: “Since we finally gained control on Jan 1, 2022, the artist’s royalties are being held in an escrow account [a legal holding account] and we have set up royalty accounting systems with Infinite Catalogue. It’s sad that people who I thought were my friends have spewed so much hate towards me. I want the company to pay the classic artists royalties and do the right thing, and now that we can finally do that all I want is a chance.”

Quite how this approach from Trax will play out remains to be seen. For Lawrence and Jefferson, this is now as much about a public show of justice. “I want to know how much money they made,” says Vince Lawrence, “because that’s going to inspire another generation of kids in Chicago.”

Marshall Jefferson takes a similar stance: “Well, I would just like to have my day in court, and see what their case is. You know, it’s been 30-something years — just bring out all these fraudulent contracts with the fake signatures, make them show receipts for money that they paid us for stuff… I would like to see what addresses those songwriting cheques went to.” He doesn’t sound bitter, more resigned to what happened, sometimes laughing at how long it’s gone on, sometimes philosophical about its impact on him: “I’m upset about it, but I don’t dwell on it — you know, I gotta move on.”

DJ Pierre isn’t a part of the current case against Trax Records and tells DJ Mag that after several decades of his music being re-released by Trax against his wishes, he finally got the rights to his Trax compositions back without going to court. However, his experience of Trax Records in the late ’80s was very similar to Lawrence and Jefferson’s: “I never had any royalties or anything. I didn’t even know the stuff was happening in Europe. In ’88 the only way I knew the records were being sold in Europe was because all the magazines started flooding Chicago asking questions about this music.”

For Pierre though, the Trax Records story exists in a larger context, where their exploitative business practices were for decades tacitly held up and supported by an industry that was only interested in profits. “I think also we should talk about how the industry, maybe not so much the media, but how all the publishers and labels and people that wanted to licence stuff and use the material, kind of turned a blind eye and kept throwing money that way, even though they knew for a fact that this money was never getting to us.”

While not attempting to absolve Trax, he feels that what happened at the label was very much part of a bigger picture of how the Chicago house phenomenon was jumped on and appropriated by the music industry: “The way we were dealt with in Chicago was almost based on how Trax Records treated us and how people said, ‘OK we can exploit them, we can do whatever to them’. But when they went to Detroit they had to be different because the artists had their own labels for the most part. So Detroit got a different respect… Everyone is pointing at Trax but really, that same mentality was all over the place.”

Pierre’s final pithy observation is that sometimes it seems the press only want to talk about the past, about ‘Acid Tracks’, Larry Sherman and Trax Records, not what he’s doing currently. This links into a larger issue: that the Chicago house innovators were involved in creating something that now makes millions for mainstream DJs — and provides a living for their agents, managers, drivers, stylists and so on — but these opportunities don’t seem to be available to the innovators themselves. It could be argued that by only looking to the past, the industry commits a similar disservice to the Chicago house innovators that was done to them by Trax — that of trading off music that made the creators no money.

Trax Records is a lengthy box-set of a story: series one is a tale of a bold new record label and a crew of young, naive, hungry producers and artists who created seminal, influential, important pieces of sonic art. In series two we see several of our young heroes propelled to success on the back of their music, but we also see them being exploited by the label. Season three tells of a record label that traded on its past success for years while continuing to display an apparent disregard for its artists. Season four — Trax Records: The Litigation Years — was the least successful of the franchise and not many people watched it. But then the Heard and Owens case delivered a huge, cliffhanger of a plot-twist and now the Lawrence et al case might just be the epic season finale we’ve all been waiting for.

We’ll give the last word to Vince Lawrence here: “Something happened. Somebody got paid. You know, there’s songs being used in television commercials and TV shows and somebody signed the licence and got a cheque. And I think that all of the people who made the stuff, need to know what it’s worth. They need to believe in their music.”

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.