Fashion’s Favorite DJ on Crossing Cultural Borders

- Interview: Adam Wray

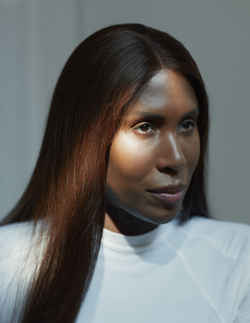

- Photography: Benjamin Huseby

“You could drop this in London and it would be the same,” says Honey Dijon, gesturing around the interior of The Apparatus Room. Nestled in the lobby of the Foundation Hotel in downtown Detroit, the lounge projects a specific sort of made-for-Instagram bougieness, Edison bulbs dangling above a bar wrought from reclaimed wood. “Same lighting, same wood, and glass, and steel. It’s the same shit everywhere.” Pure Honey: matter-of-factly skewering orthodoxy wherever she encounters it.

She is in Detroit for Movement, one of the world’s premier dance music festivals. Summer is festival season, which means a full calendar for an internationally touring DJ like Honey. The night before, she played a peak-time set at the annual OK, Cool! afterparty. The day we meet, though, she’s relaxing.

Born in Chicago, Honey has been DJing since she was a child. “My parents were pretty young when they had me,” she explains, “and I would play music at their parties before I had to go to bed. I get excited about sharing music with people—it’s just how I was wired.” Honey began going out in her early teens and came of age in the clubs that birthed house music, which gives her an important perspective on the genre’s oft-ignored origins: “This is a 30-year-old subculture that’s now above ground, and I try to convey that music from where I come from—queer, black culture. This music was started by queer people of color.”

Honey moved to New York City in the late-90s, and it was there that her career as a DJ took off. Her style is powered by a borderless intuition. She slides smoothly between disco, house, and techno, and she is as comfortable playing Berlin club mecca Panorama Bar, where she’s a regular, as she is at Art Basel or a Rick Owens afterparty.

Her work behind the decks carried her into the world of fashion, attracting figures like Nicolas Ghesquière, Riccardo Tisci, the aforementioned Owens, and Kim Jones, whose admiration gave way to collaborative friendships. For the past six years, Honey has worked with Jones to develop the soundtracks for Louis Vuitton’s men’s shows. The most recent one made waves with a brand new Drake tune written just for Jones (Drake actually offered two originals, Honey later tells me over email). She has also found time to take on speaking engagements, sharing her experiences via lectures at MoMA PS1 and King’s College London. Her calendar full as it is, she reckons things are about to get even more intense—she’ll soon release her debut full-length on Classic, the label started by her mentor and OG house legend Derrick Carter.

Over tequila cocktails and french fries, Honey and I discuss the changing demographics of dance music, dissociating in the DJ booth, fashion’s appropriation of trans culture, and the records that changed her life. Later, in Berlin—her second home—Benjamin Huseby styled and photographed her in clothes from GmBH, the label he designs with his partner Serhat Isik.

Honey Dijon wears GmBH hoodie and GmBH trousers.

Honey Dijon wears GmBH pullover and GmBH trousers.

Adam Wray

Honey Dijon

Does the world feel kind of small to you at this point?

Uh-huh. The internet changed everything. People forget that the internet—we’re in 2017, and everyone got a home computer in 2004, 2005, so we’re only talking one generation. I miss the days when I would go to London and I had to buy certain things in London. I miss the community of record stores, running into my peers, being introduced to music that I normally wouldn’t listen to. I find what the internet has really done is close people’s minds. We have all of this information, but people only look for things that they know or that they’re comfortable with.

And they still want to be told what they want. You can watch it happening on Discogs. Some big DJ will play a track no one has heard and it goes from being a $5 record to a $50 record overnight.

Which is stupid. Just because somebody doesn’t know it doesn’t make it good. There’s no discernment anymore. Even fashion has changed for me. That vocabulary has become so democratic and the information is so accessible that I kind of miss when fashion was elitist. I kind of miss when there were tribes of people that spoke different languages. Now it’s just like eating at McDonald’s. It’s the same in every city. It’s going to taste the same, and it’s going to look the same.

Given that you’re playing constantly, how do you challenge yourself and keep it fresh?

I’m still excited about the music! I approach DJing as an art form or craft. For me it’s like someone painting a picture, or writing music, or designing something. The hard part is that it’s not every day I have something to say as an artist. You can’t force inspiration, and when you play so much, it’s not like you get as many great records as you do gigs. So it’s about reshuffling these records that I’ve been hearing for the last three weeks over and over again so that I’m still excited. Frankie Knuckles always said the moment you become more important than the music, you’re done. And I live by that.

In house music’s early days, the DJ was not necessarily the focal point of the party, and at some point that changed. Is that something that you consider when you’re playing? Are you thinking about how you look while you’re performing?

Yes. And I relate that back to bands—the look is important. I’ve always had a relationship to style. When I discovered the first musicians that I loved, I would sit and look at what they wore and what the album cover credits were—who took their picture, who did their hair. I love the whole idea of approaching DJing and music as a cohesive project, as an art thing. This isn’t anything new, it’s just that now DJ culture is more visible than it was before. DJing and DJ culture is becoming a lifestyle thing, whereas before it was really just a subculture.

“IT’S FUNNY HOW PEOPLE THAT CREATE THE CHANGE VERY RARELY GET TO EXPERIENCE THE CHANGE.”

There’s this idea right now that subculture is dead. Do you think that’s true?

There’s always going to be something that’s underground, always. There are subcultures out there, but as soon as someone at a magazine or a website finds out about it, they blow it up and it goes viral. The life expectancy of a subculture is a lot shorter.

Things don’t get time to develop.

We don’t have time to expand on a thought! No one does. Everyone is having a reaction against everything, no one is actually interacting.

Do you feel like the culture of dance music has shifted towards consumption?

No one is bringing anything to the party! You go to the club and no one’s wearing color, no one’s bringing attitude. They’re all standing there, wearing these bland clothes, looking at the DJ—who gives a fuck? I remember when I started going out I actually had to have a look or an attitude to get into the party. I was there because I was creating part of the atmosphere, not taking something away from it. I wanted to contribute to this music and I wanted to contribute to this culture. I come from that school of thought where art, music, fashion, clubbing, all of it was a cultural center. This was where people—I have a saying: meet, mate, and create.

We were speaking earlier about how audiences have changed…

They’re straight and white. We can go there.

Let’s go there, then. What do you think changed that—

The music changed! People of color and queer people have a certain sound that’s really emotional and spiritual. I’m not saying that what other people do isn’t, but there’s a certain sound and a certain technique and a certain emotion that comes from disco and early house. The music has become more monotonous. We have technology now where DJs don’t actually have to know the craft of DJing—that changed. I’m not saying things should stay the same, obviously you need to evolve, but, sonically, music changed, and you don’t see a lot of people of color at the club anymore. You don’t see a lot of people of color dictating parties, or festivals, or record labels, or editing magazines. It’s funny how people that create the change very rarely get to experience the change. This music and this culture has been colonized by heteronormative, cis-gender, white people, and I think we’re just seeing a reflection of that heteronormativity.

Honey Dijon wears GmBH jacket.

Do you see things opening up in any way?

Yeah, because I think queer people are becoming less afraid. Queer people and trans people are more visible and are less fearful of the fallout from being vocal. I can’t be something that I’m not, so why should I have shame because I’m not that? And what do I want my life to be? I think one of the great things about the trans movement is that it’s breaking down binary gender roles, and it’s sparked the conversation of what it is to be straight, or what is it to be a man, what is it to be a woman. Or, if I have this body but I’m attracted to this person, what does anything mean anymore? We’ve all been sort of languaged into experiences. Our whole identity is basically language, and most of our identities have been designed by white, straight men. I realized I couldn’t be a white, straight man, so why was I trying to follow that value system?

When you were growing up you collected not only records, but magazines, and art books, and so on. Have you always had that collector’s gene?

I think what it was for me, now that I look back, is I was very ostracized. I grew up in a time when there was no language to define my gender, so I found solace in art, and music, and fashion. These were beautiful worlds and I was not in a beautiful place. Every time I walked out of my door it was very ugly for me, but when I came into my room and I surrounded myself with all these beautiful art forms, it sort of fulfilled me and gave me hope. It was the only thing I had that was mine that I could control, and it was the only thing that made me feel good. I just bought as much and learned as much as I could. I found out about Irving Penn by just going to my local library and looking in the photography section, you know? There were early _GQ_s around the house, and that’s how I found out about Bruce Weber, and New York, and Studio 54. And then by going to Wax Trax! Records I discovered i-D Magazine, and The Face, and BLITZ, and that was my introduction to London. I collected these things because they were my entry way into culture.

What do you think you do as a DJ that no one else can do? Or that no one else does as well?

I’m not sure I’m comfortable with that language, because I believe that everyone has a unique voice when it comes to expression in music, and I don’t think one is better than the other. There’s enough sunshine for everyone. I’ll say this: my voice is my life experience of being in different environments from the small, gay black clubs, to the big New York clubs, to the London clubs, from Chicago to Detroit. I’ve experienced music presented in many different environments, and that experience presents itself in how I perform music to people.

And no one else has that exact experience.

And that gives me my unique voice. Is it better than someone else’s? It’s just different.

That’s a much better way of putting it. Do you want another job?

I always say, when I show up, for these next two or three hours, this is the experience you get, then you can go back to your regularly scheduled programming. But for these three hours, we’re doing it this way. I think what really gave me that level of confidence was going on tour with Disclosure. I was playing in the middle of America to audiences that didn’t know who the fuck I was. I was opening for two 20-year-old British white boys, and this black, trans woman from the city of underground house music had to entertain them in her own way. I was grateful for that experience. It made me realize that there was something I could contribute to this, and that I had to really believe in what I was doing for other people to believe in it.

Honey Dijon wears GmBH pullover.

Can you just tell me a bit about how you made your way into the world of fashion?

Accidentally. When I was growing up, especially as a trans woman, the ultimate form of validation was being a model. Because there were no mirrors of affirmation for me as a young trans person. Even when I see a lot of trans women today, they romanticize hyper-femininity. That’s not me. I don’t like tight dresses and high heels. That’s not my story. I’m more into Margiela, Ann Demeulemeester. I like more ideas in fashion. I don’t dress for the male gaze, and I think trans women, wanting to be seen as who they are, still buy into a lot of cis-gender, heteronormative beauty standards. We spend a lot of money trying to be invisible. Passing, to me, is another word for invisible. I kind of feel controversial talking about that, because I’m not trying to betray my sisters, but I realized that even in the trans community my beauty standard was very different. High heels hurt. I’m running around the world, I don’t have time to be running around in some heels, you know? And, honestly, I don’t need a man at this point. I think one of the great things about being a trans person is redefining relationships and what they look like.

But I got into fashion just DJing. Being in New York City where fashion, art, and music co-exist, I was DJing at a lot of gay bars. Most fashion designers are gay, so they would hear me at these parties and evidently they liked what I was doing, so I started to get invited to fashion events, and then that led to working with fashion houses creating music and soundscapes.

So when you’re sitting down with Kim Jones to work on the music for a Louis Vuitton show, where do you start?

Kim knows his shit. And with him it’s really easy, because I know what he likes and we just speak the same language. He just really trusts me. I’ve met so many people through him—one season I worked with Giorgio Moroder, one season I worked with Nile Rodgers, one season I worked with Nellee Hooper. Can you imagine? Like, I’m sitting here talking to fucking Nile Rodgers! Now if I email Nile Rodgers, he’ll return my email, you know what I’m saying? The fact that I get to meet these people that changed music is amazing. And Kim has allowed that to happen. And, you know, we just really get on as geeky people. He’s given me Keith Harings and I’ll give him Frankie Knuckles mixes that never came out. We share culture.

For me, dancing works out a kind of physical intelligence that I don’t access in other places. Like, a mind-body connection. How does DJing make you feel?

Free. It’s almost like when you’re having really good sex with somebody, and there’s no inhibition, or there’s no thought. You’re not thinking, you’re feeling. I have no concept of time. When I’m DJing sometimes, I don’t know if 10 minutes have gone by or 10 hours. I feel really free, and I feel really lustful. I get so sexually turned on when I get in the zone.

“I CAN’T BE SOMETHING THAT I’M NOT, SO WHY SHOULD I HAVE SHAME BECAUSE I’M NOT THAT?”

I’m a really anxious person, so for me, when I can get into that zone, all the other stuff stops.

It’s like a really great fuck, and you never want it to stop. That’s the great thing about sex—when you have really good sex you don’t want it to stop, and then you become addicted. And then the other person does something to fuck it up, and then you become obsessive because you want that fix again. I feel like that. I need that fix all the time.

What’s your favorite sound?

The ATM dispensing cash. Actually, my favorite sound is kissing.

Good one—it’s a very specific sound. I’m going to ask you about some specific records. Can you tell me a record that works on any dance floor in the world?

“French Kiss” by Lil’ Louis. It’s just one of those records that no matter if you’re playing house, techno, or disco, everyone knows it and it still sounds as special as when it was made 30 years ago. You can play “French Kiss” anywhere in the world and everyone will freak out.

A record that always brings you joy?

“La Vie En Rose,” Grace Jones.

A record you want played at your funeral?

“Welcome to the Pleasuredome,” Frankie Goes to Hollywood.

A song you wish would play every time you walked into a room?

“When You Wake Up Tomorrow,” Candi Staton.

Honey Dijon wears GmBH t-shirt and GmBH trousers.

And a record that changed your life?

There are so many—you can’t do that! “Bostich” by Yello. “Join in the Chant” by Nitzer Ebb. “Mesopotamia” by The B-52s. Oh my god, like, “Relax” by Frankie Goes To Hollywood. “Brighter Days” by Cajmere. “One More Round” by Kasso. “Cherry Pie” by Sade. A Seat at the Table, the entire album by Solange—that album is a masterpiece. Marvin Gaye’s “After the Dance.” Are you kidding me? Like, fuck. “A City That Never Sleeps,” The Eurythmics. “Julia,” The Eurythmics. I could go on, and on, and on, and on. “White Boy” by Culture Club. Kissing to Be Clever is one of my favorite albums. That changed my life. I’ll tell you a funny story—I never talk about this. I remember when I was a kid, before I knew what trans was, I went to the mall and I saw Kissing to be Clever, and I just kept staring at it, and staring at it, and staring at it. I didn’t know why I was staring at it, because, like everyone, when I first saw Boy George I thought he was a girl. Something inside me was like, “There’s something different.” I couldn’t put my hand on it because I didn’t have the language to define it. For many years, I thought I was androgynous, until I started to find out more about that. So, that album cover was probably what changed my life. Crazy.

It’s so amazing how music can give you an inroad to examining things you didn’t even know could be things.

This is why I don’t take dance music lightly, because it was how I experienced things. This was really a music and culture created by people that weren’t allowed to be in other spaces. You have to understand, Chicago was very segregated—there were very few places for queer people of color to go. They created house music for themselves, and they were dressing themselves. No fashion brands were putting black people in ads. Even today, with this conversation with trans people in fashion, who is it benefitting? Whose advantage is it working towards? Is having a fashion brand validate your beauty giving you your sense of worth? Because you’re actually giving them the worth, and you don’t even realize it. Harriet Tubman said that she would have freed a lot more slaves if they didn’t know they were slaves. Think about that for a minute.

I recall seeing a subway ad for a genderfluid clothing line from Topman or something recently. My gut reaction to stuff like that is to be critical. Like, they don’t actually give a fuck about making the world a safer, more hospitable place—

They want to make money. And they want to seem relevant and cool.

“WHAT THE FUCK AM I GOING TO DO WITH A LEGACY IN MY CASKET?”

For sure. It’s always going to be about making money. But advertising can influence culture, broadly speaking, so I sometimes wonder, if someone in a small town in Kansas sees that ad and it helps them understand themselves a bit better, or helps someone understand the issues better, is it a bad thing?

No, it’s not a bad thing, but you’re talking to a person that was able to do that for themselves without advertising. If I was able to be a black kid from the south side of Chicago and manifest into who I am today, it’s hard for me to empathize with that. The survival rate for someone like myself is zero. Zero. So, I think it’s great if that does happen, but I always feel like there’s an agenda with these corporate brands. If this dialogue wasn’t already in culture, would they be doing it out of good conscience? No. So, who is it benefitting? I really want trans people and non-conforming people to take their own power and stop looking for these straight, corporate brands to give them worth, because that’s not how it works! The thing about fashion is that it changes at the drop of a hat. Once they decide that trans is last season’s news, you’re out. That’s just how it is.

Do you ever think about your body of work in terms of legacy?

What the fuck am I going to do with a legacy in my casket? Legacies are for the living. My ego is not that deep that I need people to remember who the fuck I was—I’m not here!

I feel you on that. The most important thing about getting older, for me, has been getting more comfortable with how unimportant I am in the grand scheme of things.

You could say the same thing about what I do. I’m not curing cancer, but at the same time…

You make people happy.

There you go. So, it’s not important, but it’s extremely important because it brings people joy. And bringing people joy is just as important as curing cancer.

- Interview: Adam Wray

- Photography: Benjamin Huseby

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.