Moodymann is famed as one of the greatest house music artists of all time, but his roots as a hip hop producer are less well known. Patrick Hinton speaks to Kenny Dixon Jr. and his former rap collaborator K-Stone to find out more

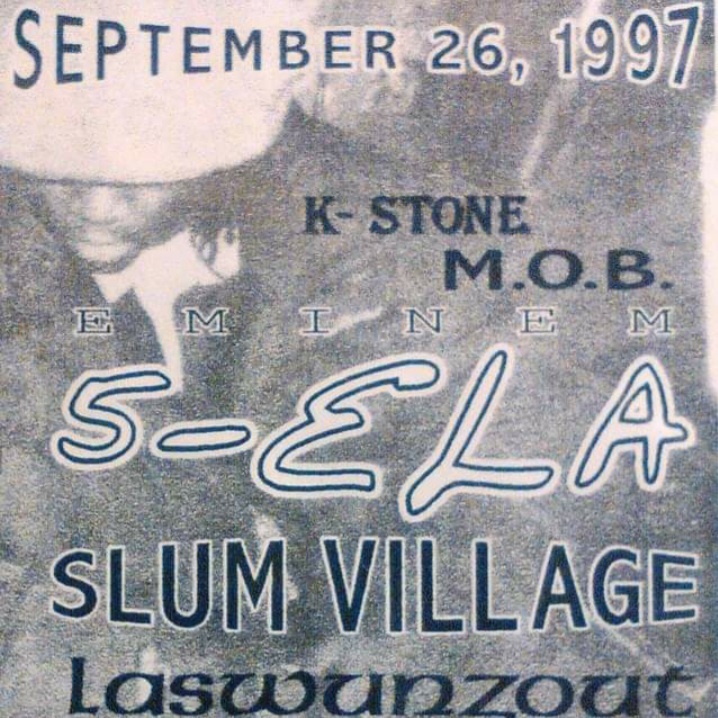

It’s Friday night, late-September 1997 in Detroit, and the first weekend of the fall season has begun. At an underground rap show in the city, a rising MC from the local area named Eminem is on the stage, which has earlier been graced by the likes of Proof and J Dilla. All are performing in support of tonight’s headline act K-Stone, featuring DJ and producer Kenny Dixon Jr., now more commonly known as Moodymann.

Music history is dotted with stories of artists who have switched genres and ascended to new heights — Daft Punk was formed from the ashes of rock group Darlin’, Skrillex first found fame as the frontman of post-hardcore band From First to Last, the Bee Gees dealt in psychedelic folk long before their falsetto-fuelled disco era — but less well documented is how Kenny Dixon Jr. spent much of his early music career making hip hop.

“You going way back now, you in the ‘80s!” recalls Kenny from Mahogani Music HQ in Detroit, casting his mind back from 2023 to his fledgling days as a producer, before he was heralded among the most important house music artists of all time. The Motor City’s music scene was a melting pot of inspiring sounds — the hip hop movement that had started in New York City in the ‘70s had taken a firm rooting in Detroit, house music influence was filtering eastward from Chicago, and the City’s own style of electronic music, soon to be known as techno, was being pioneered by Juan Atkins. Kenny was a young and keen participant, having fun and wanting to try it all.

“Every guy in Michigan or Detroit, if you did hip hop, you did electro and techno too. But most people wanted the hip hop beats,” he recalls. “You would make about 10 beats in a day; you used to just have cassettes floating around anywhere. I was just so happy to be producing stuff.”

His beats made their way onto the albums of many prominent Detroit rappers of the time, including A.W.O.L., Detroit’s Most Wanted, The Riddler, B-Def and Smiley. “Now, my beats were never a single or never got played on radio or nothing like that, mine was just a track on the album,” he says. “I was just happy to hear my track on there, to have anyone listening to it.” Getting his name out there as a musician was the goal, and he paid little attention to the commercial side of the music. “I’m at the cafeteria telling ‘That’s my beat on the album!’, you know what I’m saying? Making hip hop was getting me notorized in the streets. But definitely not my pockets!” Some times he’d get $100 for a beat, other times he’d get $200 for four — sometimes he’d sell a beat, forget he’d sold it, and then sell it again. “It was fun, it was just something we did, we didn’t think of it as a business. Half the n*****s out here was rolling dope anyway, they was making money, they just wanted their music out.”

Alongside spending his days making beats, Kenny would spend his nights DJing at house parties, and the two would go hand in hand. “We had a great time in the studio,” he recalls. “Much more of a party atmosphere compared to when I’m in the studio now. We was young! What can you say; it was popping. What we didn’t know is we was paying for all that shit.” While his name was on the streets, it was never on the album credits. “You know whose name is on all of that shit? The motherfucker who was paying for the studio time!”

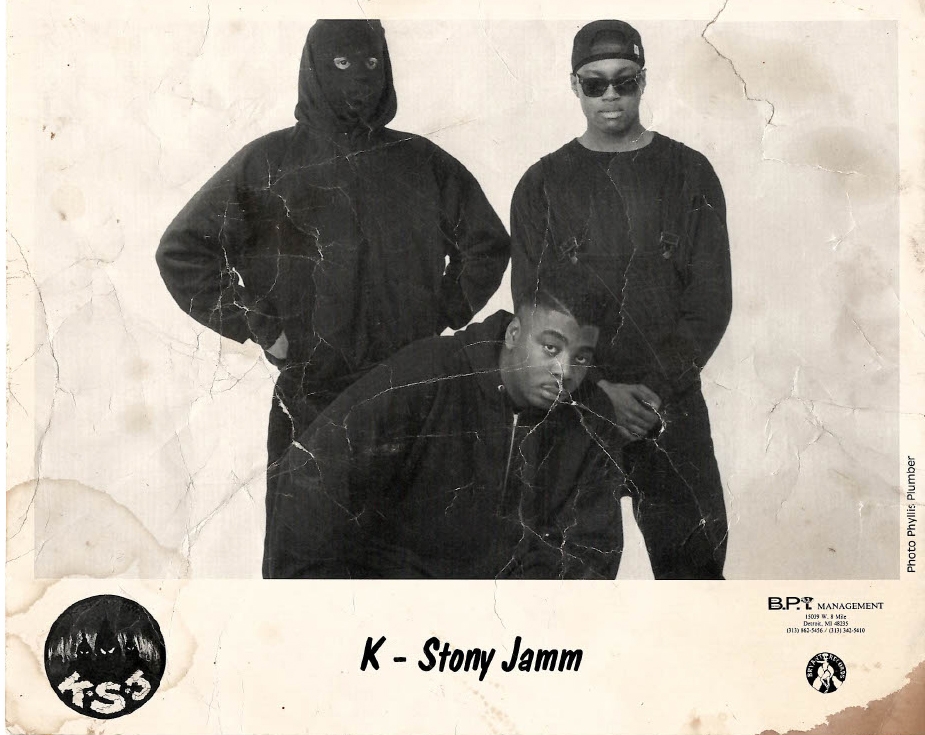

An exception is his work with Kevin Bailey, a rapper who grew up in the same neighbourhood as Kenny and went by the name of K-Stone. They became friends when Kenny was using the alias Mr. House, DJing at all the local house parties and playing house music. When K-Stone started to get serious about doing music, he wanted one of his older brothers, who was friends with Kenny and often played alongside him, as his DJ. “But my brother didn’t really work out in the group,” says K-Stone, speaking from Atlanta where he now splits his time with Detroit, “so we ended up getting Moodymann to do it.” When he was looking for beats to rap on, he landed on the same approach.

“We used several different producers first, but Kenny started to play around with different records and different samples over beats. I think I was one of the first guys that he produced rap music for,” says K-Stone. Their group also featured a producer called K9, real name Kahlil Oden, who primarily worked the drum machine, while Kenny would find records to sample and loop over the beats. “I can find a diamond in damn near anyone’s album,” declares Kenny enthusiastically. “I’m still probably Detroit and the world’s greatest music fan.”

“We loved his production because he always used the funkiest old records,” says K-Stone. “Moody would pick some of the craziest loops, old skool loops from different types of records. He would use breakbeats and vocal samples to create various different hip hop grooves and beats. We would come up with all kinds of dope ideas.”

They ended up living together in Kenny’s dad’s house, around their late teens to early 20s. “We spent quite a few years in the basement making music and just dreaming of becoming stars,” recalls K-Stone. “Those were the good years man, we had a real good time starting out in the music industry.”

In 1989, it looked like that dream was about to become reality, when K-Stone, K9 and Mr. House were offered a joint record deal by Warner Bros. Records, the same label as Kenny’s idol Prince. But then tragedy struck: K9 was shot and killed in Detroit, and the label pulled the deal. “He was actually killed two days before we were supposed to sign it,” reveals K-Stone. “Even though it wasn’t any fault of ours, the label declined the deal because they didn’t want to get involved in any violence, they was thinking it was gonna be some violent street group.”

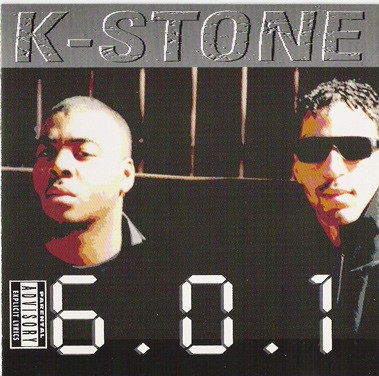

The K-Stone and Mr. House partnership carried on for years beyond that and enjoyed some solid success, including numerous tours, signing to Atlanta’s Ichiban Records, and the release of albums such as ‘6.0.1’, which featured Moodymann collaborating with Geto Boys producers DJ Ready Red and Sir Rap-A-Lot, and ‘313’, which K-Stone claims “actually started the 313 saying around Detroit,” an area code nickname for the city referenced everywhere from 8 Mile scenes to DJ Stingray 313’s moniker. But it never took off for them in the way it did for the likes of Eminem and J Dilla, who once opened for them at shows.

Kenny had always loved house and techno music — even when he was making hip hop, he cites Juan Atkins as his main inspiration. “I don’t give a fuck what side of town you was from or what you like, you was fucking with Juan Atkins, in all genres. Cybotron was killing the city of Detroit,” he says of the early ‘80s. “Before anybody knew what that was, we was rocking that new shit. That Cybotron was aggressive. Motherfuckers was mad. It was a product of our environment.” He labels his gangsta rap work with K-Stone: “Most definitely Detroit production inspired — a Detroit product.”

As with the bulk of his hip hop beats, his early house and techno productions exist only on uncredited cassette tapes that would be passed around fellow DJs to play. “We wasn’t playing records, we was playing house music from people that was making house music — cassettes people gave us in the neighbourhood, their version of house music. None of that stuff was pressed up on labels or anything like that.”

That wasn’t for want of trying. “I was making that kind of music long before I got my own label together. I was shipping that tech and house off to record labels, and no one wanted it,” he says. “That’s why I started putting it out myself.” It’s humbling to think about how many more would-be legends we might also know about if they’d managed to do the same. “Some of the best producers I’ve ever heard are still unheard of, and that was just the other cats in the neighbourhood that was just killing the beat game,” says Kenny. “But they were just up in other shit, doing other things.”

He founded his KDJ imprint in 1994 and quickly started making waves around the world with records released under the name Moodymann, cutting through the clean house sound of the time with a grittier approach. His debut album ‘Silentintroduction’ dropped in 1997 via Planet E, a classic 10-track LP that meant his path to house and techno legend status was assured. He may have had a lucky escape with those initial label rejections, considering the shady business practices also being employed by prominent house music imprints of the time, such as Trax in Chicago, meaning many of house music’s innovators do not own the rights to their pioneering music.

Meanwhile, K-Stone kept going on the hip hop route, changing his rap name to Dogmatic in 1998, joining up with Proof to form their Promatic partnership before Proof was killed in 2006, and most recently launching a new project called Detroit Underdog Kings with three of his sons. Kevin and Kenny remain close friends, despite going their own ways musically.

“Once he started to produce techno, his first couple of Moodymann records did so very well that he just kept going in that direction to become who he is today,” says K-Stone. “Moodymann’s music is definitely rooted in hip hop, it started that way.”

The hip hop origin has carried through Moodymann’s music: in the energy, the attitude, the grit and the production techniques. He’s still using an SP-1200 and an R-8. “It’s not like I’ve changed the way I done anything,” reflects Moodymann. “I’m the one with the dope, you know, I like my product uncut.”

Patrick Hinton is Mixmag’s Editor & Digital Director, follow him on Twitter

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.