By Mark Savage

BBC Music Correspondent

Published

“I’m on that new vibration,” sings Beyoncé on her new single, Break My Soul. “I’m buildin’ my own foundation.”

The foundation of her new sound actually dates back to the diva house movement of the 1990s, with its deep grooves, soaring melodies and insistent four-four beats.

She even shares the writing credits with Allen George and Fred McFarlane, composers of the timeless house classic Show Me Love for Robin S.

Weirdly, Break My Soul neither samples nor quotes their song. It simply uses the same bass sound, a preset on the infamous Korg M1 keyboard. But Beyoncé has always been careful to acknowledge the black creators who have influenced her.

Sending a few royalty cheques to the creators of Show Me Love (or to their family in the case of McFarlane. who died in 2016) is a very Beyoncé gesture.

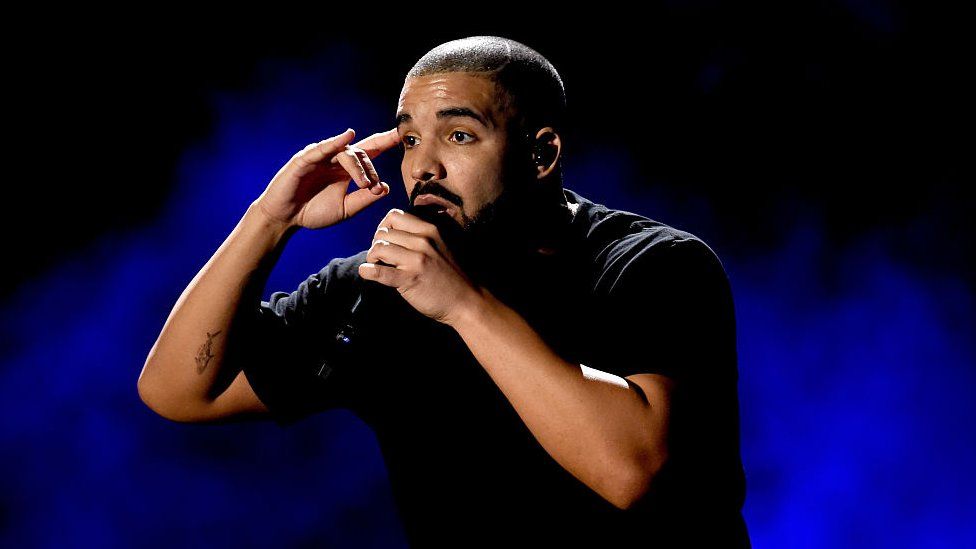

The release of Break My Soul comes just a couple of days after Drake’s similarly club-inspired new album, Honestly, Nevermind.

Tracks like Falling Back and Massive also draw on the hypnotic bass and chunky piano chords of 90s house, with Drake enlisting an all-star cast of house and electronic music producers like Gordo, Rampa, Black Coffee and Alex Lustig.

The question is, why now?

Part of the answer is, almost predictably, the pandemic. Like Lady Gaga and Dua Lipa before them, Drake and Beyoncé are eulogizing the redemptive power of dance in an unrecognizable world.

“I just quit my job… they work me so damn hard,” mutters Beyoncé in her lowest register, referencing the Great Resignation. A prominent sample of New Orleans bounce musician Big Freedia then urges listeners to “release the stress” and “release your mind” before a gospel choir turns up for the song’s ecstatic climax.

“With all the isolation and injustice over the past year, I think we are all ready to escape, travel, love, and laugh again,” Beyoncé said in a recent interview about her forthcoming album. “I feel a renaissance emerging, and I want to be part of nurturing that escape in any way possible.”

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGESDrake’s album is more concerned with relationships (guess what everyone, he’s a bit sad about them) but even he promises to “throw a party for my day ones”, while bragging “I’m a night owl, this a different mode”.

There are dozens of different genres that Drizzy and Queen Bey could have chosen to soundtrack their dancefloor escapades. But both are smart enough to know the extra cultural weight that house carries.

It emerged in a Chicago venue called The Warehouse, which initially operated as a members-only club almost exclusively frequented by black and Latin-American gay men.

“It wasn’t meant for straight people at all,” recalled house pioneer Jesse Saunders last year. “We’re talking the ’70s. When you’re young, Black, Latino and gay, you have no place in Chicago, because Chicago is one of the most segregated cities in the country, if not the world. Nobody wants you in their club. Nobody wants you partying. So they built their own… just for gay men, not even gay women.”

The club’s star DJ was Frankie Knuckles, who would use a reel-to-reel tape to create loops and “pause button remixes” of his favourite disco tracks, making them last a little longer.

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGESIn 1983, he acquired a drum machine to enhance his mixes – and that combination of stripped-back, insistent beats with elements of cult disco classics defined the house sound.

The music’s sexuality was “blunt” and “blatant”, wrote Bob Stanley in his book Yeah Yeah Yeah: A History of pop music. “That rush to orgasm was clear in its ebbs, flows and jump cuts between dark chords and uplifting piano breaks.

“Unlike disco, this wasn’t music made by musicians, it was made by clubbers for clubbers.”

By the late ’80s, it had broken out of underground clubs and made its way onto the pop charts, helped by artists like Inner City, the Pet Shop Boys and Madonna – whose house anthem Vogue became a worldwide number one in 1990.

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE,GETTY IMAGESThe music’s origins in black and queer spaces has often been overlooked. But Beyoncé makes it explicit in Break My Soul, embellishing her familiar theme of self-empowerment with a rap from Big Freedia, who has been a fierce advocate for LGBTQ+ rights after experiencing homophobia in the early days of her career.

“We weren’t treated equally, being that we were gay,” she told Billboard magazine last year. “We were working for chump change. Over time, things started to change, but in the beginning, it was not so easy. It was not so accepting.

“People were in shock that they had these gay artists out in New Orleans that’s doing bounce music and making the girls shake all over.”

By building a bridge to black and queer subcultures, and releasing their music during Pride month, Beyoncé and Drake are doing more than just plundering their record collections for ideas.

And if their new records encourage people to check out Cece Rogers’ Someday, or Marshall Jefferson’s Move Your Body, or The Nightwriters’ Let The Music Use You – well, that can only be a good thing.

Follow us on Facebook, or on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts. If you have a story suggestion email en****************@bb*.uk.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.