The 1972 track was a favorite at David Mancuso’s Loft and sampled by the pop giants like Michael Jackson and Rihanna

BILL BREWSTER

26 MARCH 2020

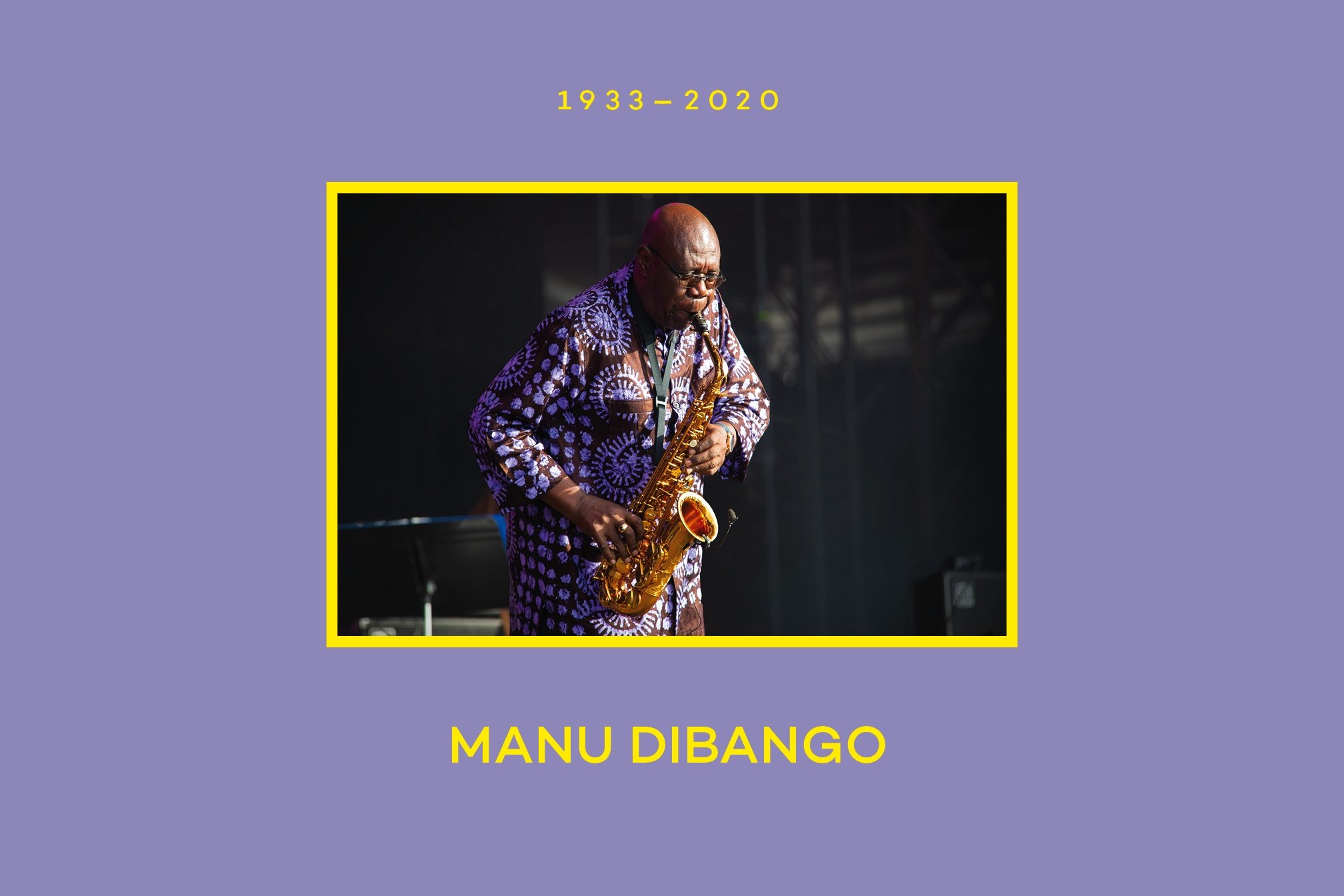

Saxophonist Manu Dibango, who died on March 25 of COVID-19, was an early champion of African sounds in Europe and worldwide, long before the notion of so-called “World music” ever existed. Although his big breakthrough as a solo artist came in 1972 with the breakout hit ‘Soul Makossa’, he had already been playing for 20 years in Africa, Belgium, and France.

Born on December 12 in 1933 in Douala, Cameroon’s wealthiest city, to a civil servant and fashion designer, Dibango was a multi-instrumentalist, best known for saxophone but adept on vibraphone and piano, too. In the 1950s, he joined the ever-evolving Congolese band African Jazz whose travels eventually took them to Paris, where he swiftly became part of a fertile ’60s musical scene. He recorded for the L’African Team De Paris, which emerged from the ashes of African Jazz, The Guerrillas, which included Slim Pezin – who later played guitar on scores of disco hits – as well as his own solo material.

Read this next: No more 4×4: How sounds from the Global South stopped club culture stagnating

But it was ‘Soul Makossa’ that made his name. Originally recorded as a B-side to ‘Hymne de la 8e Coupe d’Afrique des Nations’, a jaunty paean to the African Nations Cup which was staged in Cameroon that year, it was re-released on the Fiesta label, and by a happy accident discovered in New York.

“One of the most spectacular discotheque records in recent months is a perfect example of the genre: Manu Dibango’s ‘Soul Makossa’,” wrote Vince Aletti for Rolling Stone in 1973, the first-ever piece published on the disco phenomenon. “Originally a French pressing on the Fiesta label, the 45 was being distributed by an African import company in Brooklyn when a friend brought it to the attention of DJ Frankie Crocker. Crocker broke it on the air on New York’s WBLS-FM, a black station highly attuned to the disco sound, but the record was made in discotheques where its hypnotic beat and mysterious African vocals drove people crazy.”

Read this next: 10 classic tracks from David Mancuso’s Loft

The US release made the Billboard Hot 100, eventually peaking at 35, with scarcely any radio play. The success of ‘Soul Makossa’, coupled with other club hits like ‘Love’s Theme’ by the Love Unlimited Orchestra, caused a revolution in recording industry promotion, which had previously entirely relied on radio airplay, with the birth of club promotions departments.

The song itself has become one of the most well-worn tropes in modern popular music, its memorable chant being re-heated and interpolated countless times (not counting the scores of cover versions), from 70s sex comedy theme ‘Sesso Matto’ by Armando Trovajoli to Michael Jackson’s ‘Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’’ and subsequently ‘Don’t Stop The Music’ by Rihanna. In 2009 Dibango filed a lawsuit against the two pop giants. Jackson had previously admitted to using the hook without permission and settled out of court, but the King of Pop again failed to seek Dibango’s permission when Rihanna came knocking for the vocal chant in 2007. The court case failed in light of Dibango already successfully applying for a writers’ credit on Rihanna’s hit in 2008, with the court deciding this ruled him out of any further claims on the track.

As a sample source, he’s been almost as fertile a source as James Brown, with ‘Soul Makossa’ drafted in for everyone from early rappers Poor Righteous Teachers’ wholesale lift on ‘Butt Naked Booty Bless’, to J’Lo’s ‘Feelin’ So Good’, and even Bristol’s Addison Groove reworking it devastatingly a couple of years ago on ‘Changa’. Elsewhere, The Chemical Brothers made judicious use of ‘Ceddo’ on ‘Battle Scars’, while ‘New Bell’, a big club record during the rare groove period in 80s London, was lifted for Busta Rhymes’ ‘Keepin’ It Tight’.

Dibango was far from a one-trick pony. Over a long and varied career, he worked with African luminaries such as Youssou N’Dour, Salif Keita and juju giant King Sunny Ade, recorded over 50 albums during his seven decades as an active musician, and dabbled in everything from rumba and disco to electro and shone at most. His underrated 1981 album, ‘Piano Solo’, showed just how effortlessly versatile a musician he was, with not a saxophone in sight.

He leaves three children and a vast and fathoms-deep catalog of incredible music.

Bill Brewster is a regular contributor to Mixmag. Follow him on Twitter

Read this next: Get the best of Mixmag direct to your Facebook DMs

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.