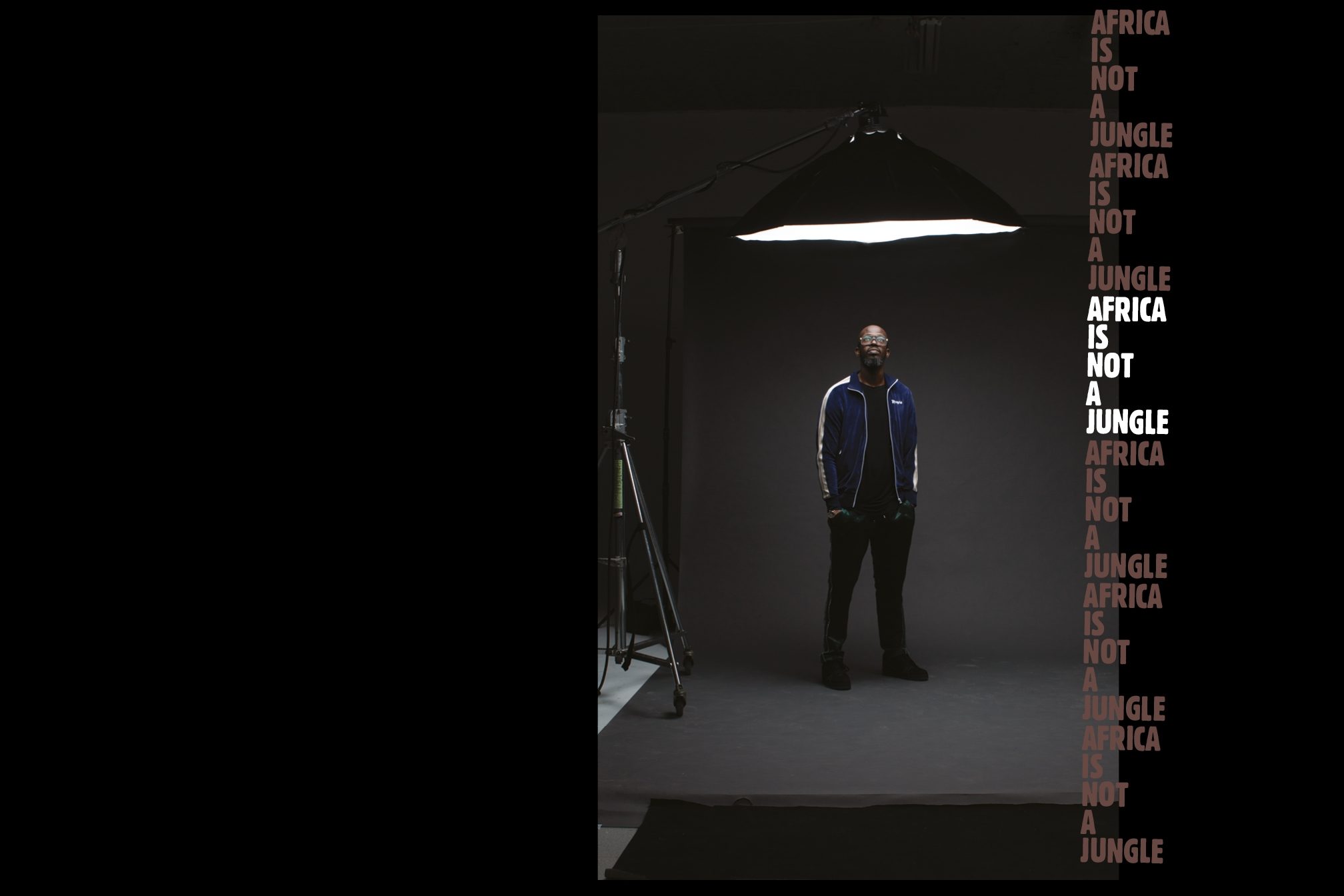

AFRICA IS NOT A JUNGLE: HOW BLACK COFFEE IS LEADING A MUSIC INDUSTRY REVOLUTION

“It’s a revolutionary decision, where we dismantle the industry as it is; so we own everything and are in control of our own destiny.”

WORDS: DAVID POLLOCK | PHOTOS: JOE PLIMMER & HENRY MARSH | STYLING: LEWIS MUNRO & RYAN HING | HAIR: BEE MAKINA

28 AUGUST 2019

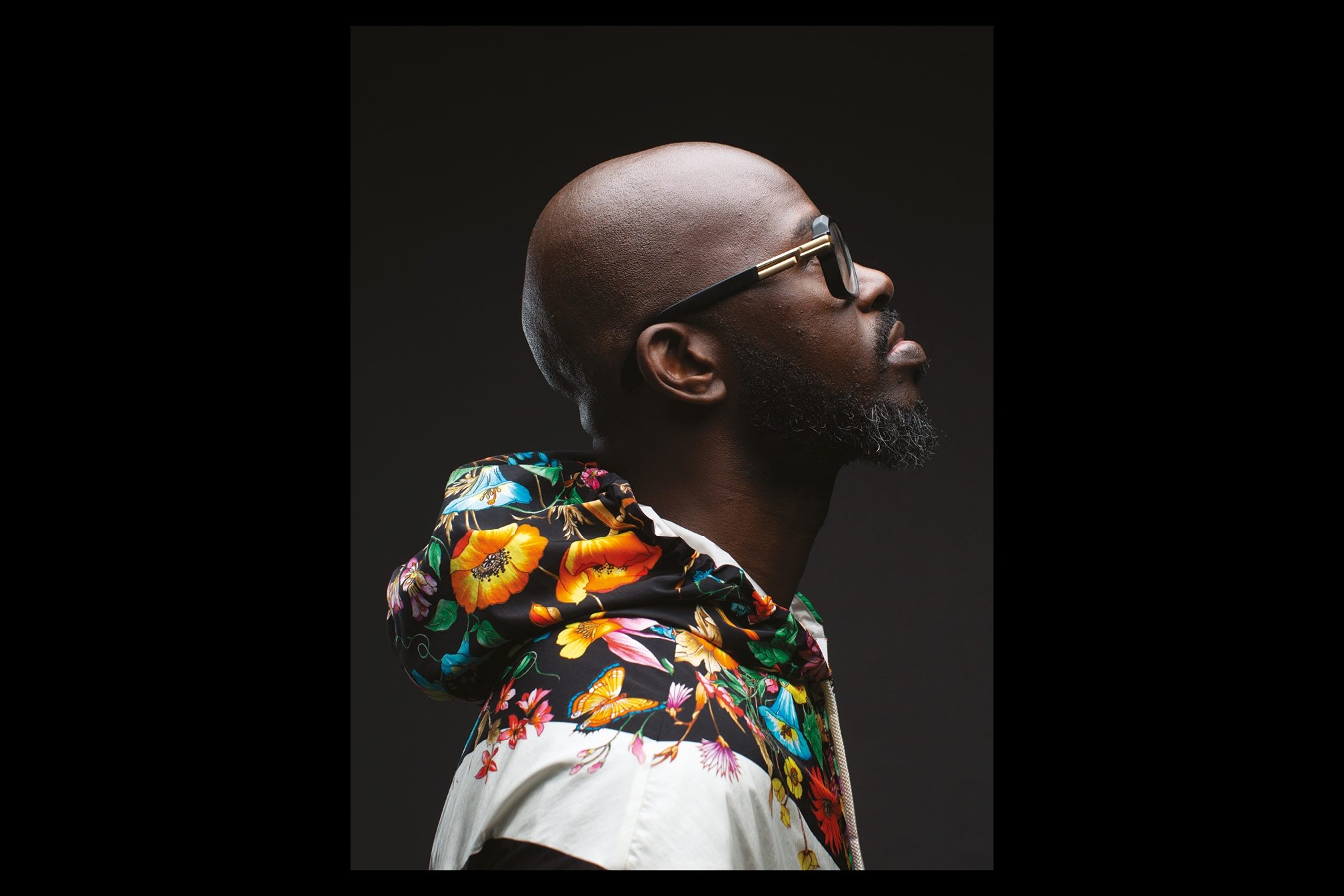

For Black Coffee – DJ, producer and guiding light of the movement to broadcast the potential of South Africa’s future club stars – Africa Is Not A Jungle is much more than just the bespoke, self-curated clubbing brand he drops into festivals in SA, and hopes to introduce to the world. It’s a motto to live by, a reminder that stereotypes about, and ignorance of, his home nation could obscure a glittering array of creative talent.

“Africa is Not A Jungle is a platform for African producers and DJs, and I hope it goes beyond the continent,” says Black Coffee – real name Nkosinathi Maphumulo, or Nathi for short. He’s speaking to Mixmag in the kind of situation which perfectly demonstrates the level of stardom he’s attained. Currently living in Barcelona, but on the White Isle over the summer for his successful Saturday night residency at Hï Ibiza, he’s being chauffeured while we speak from our photoshoot to the airport for a gig in Italy that evening alongside his countryman, Themba.

“We fly this platform into festivals,” he continues. “It’s about having our own stage and trying to pioneer a certain sound, but with a global appeal on the dance scene.” Does he hope it will address a lack of awareness elsewhere about the wealth of creators active in South Africa? “That’s exactly it,” he says. “Eighty, ninety per cent of the music I play is made by these artists, but most of the songs aren’t available; there’s no record label structure [in South Africa] to release them. I wanted to showcase some of this music, not just in Europe but also in South Africa, where these artists are still underground.

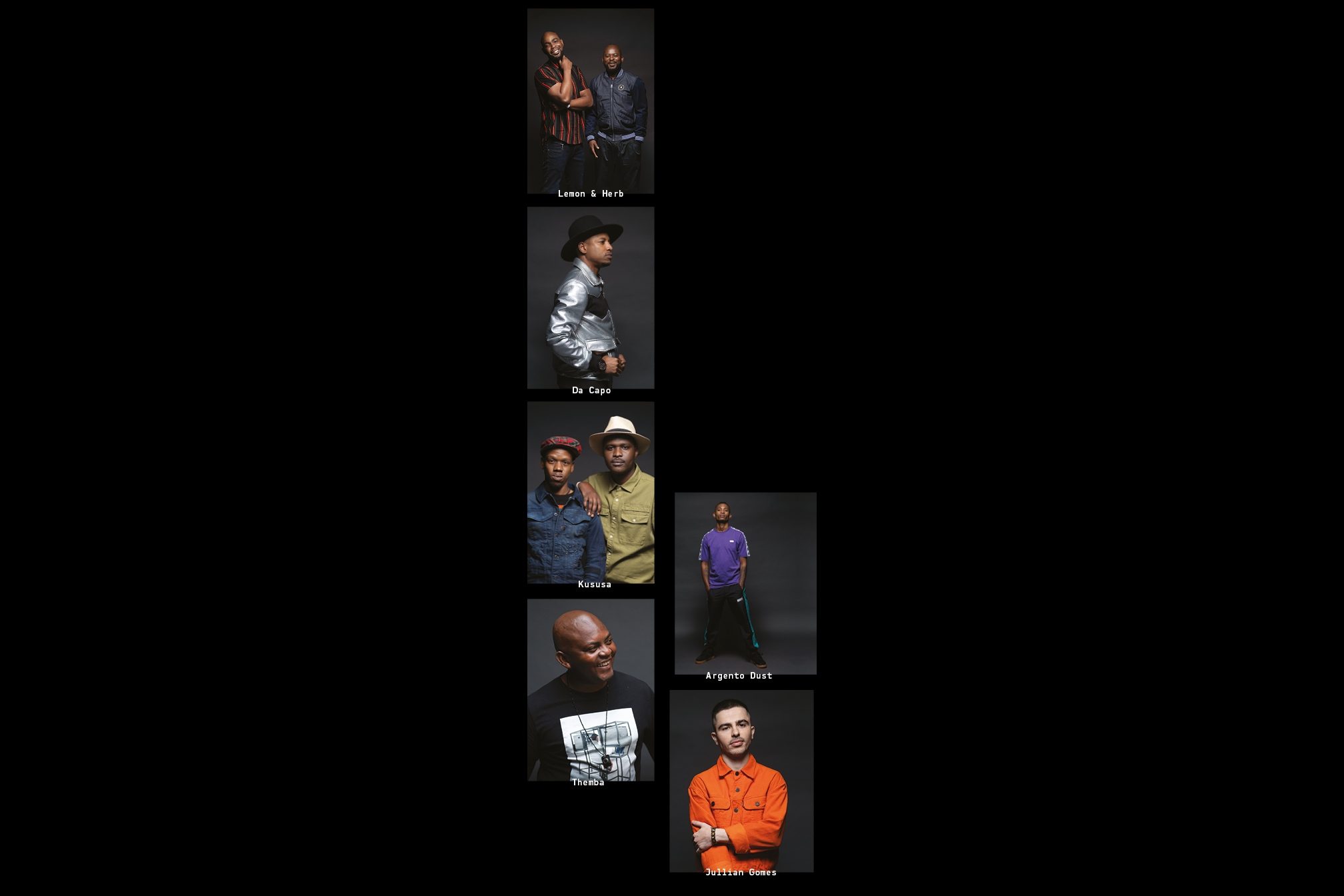

The platform will showcase them first at home, and make sure we create solid roots as we grow outside the continent.”In the meantime, his Hï Ibiza residency is doing much of this work, with big names like The Black Madonna, Damian Lazarus and Kölsch appearing alongside rising stars from SA including Culoe de Song, Themba, Lemon & Herb and Da Capo. A number of these artists are featured in this article, and their skill and vision is a testament to the untapped potential of South Africa’s music scene, and while it’s true there aren’t as many women breaking through at this level yet, DJ Zinhle is one established DJ, and Thandi Draai is a young producer to watch out for.

The plan is not to put these artists in front of major labels and get them big deals. In fact, Nathi recoils at the suggestion. “No, I’m not for that at all,” he says firmly. “That’s what we’ve been relying on for years. In Africa we’ve always been relying on Europe to come and save us, to do things for us. There was a big hoo-hah about Spotify coming, but it’s time we as Africans do our own thing, do our own Spotify. It’s our market: we know it best.”

The internet is key – and for all its emerging problems, Nathi sees the promise of democratization it offers as being ripe with potential for artists in SA. “It’s time we made our own record labels because we make the music,” he says. “It’s time we had our own art galleries and museums because we own the art and we’re great at it. For me, it’s about independence and having one voice, and asking how we can support our talent in a meaningful way. It’s like a revolutionary decision, where we dismantle the industry as it is; so that we own everything, and are in control of our own destiny.”

Black Coffee’s own story is well known by now. He found his way from beginnings which can only be described as humble in the Durban township of Umlazi to fame in South Africa and – for the last half-decade – recognition as one of the world’s top DJs and club producers. His compatriot and friend Themba marvels at the example he’s set, telling us that the idea that a young musician from a South African township might one day work with an artist of – say – David Guetta’s level of fame was less a wild ambition and more a stone-cold impossibility before Black Coffee arrived.

One promoter we spoke to in the country pointed out that the level of deprivation in the townships is almost unimaginable to a European audience, and expressed great respect for those artists who manage to do what they need to carve out a career in the face of poverty. But self-sufficiency is key, in Nathi’s experience.

“If I kept saying ‘I don’t have a studio, I don’t have DJ equipment’, I wouldn’t have gotten anywhere’,” he says. “I always tell the youngsters: you don’t need to own that equipment. Do what you can, find a friend with equipment, find a club where you can practise, go play free gigs in venues. Make things happen. The equipment is not everything, everything is just the wheel – you need a stronger wheel, then things will fall into place.”

To a European audience used to compartmentalizing everything into distinct genres, electronic music from South Africa breaks down into the electronic rap groove of kwaito, the loose groove of gqom, the slowed-down garage style of midtempo and, more recently, the soulful, Pretoria-originated adaptation of piano-led house music, amapiano. Yet in practice, DJs are just as likely to mix genres under the broad banner of ‘house music’ (or afro house, as it’s often broadly referred to in Europe), in the same way, that black and white South Africans mix and meet on the dancefloor. As one promoter puts it, “the dancefloor sees no color.”

Crowds in South Africa are famously wild, though ‘destination’ city center clubs are rare. Instead, partying takes place in locations that can range from the township ‘street bash’ to stylish bars with hired DJs, and big club festivals like Cape Town and Johannesburg’s Ultra. In Jo’burg, the largest city and the recognized music capital of the country, only the few hundred capacity And Club (featuring its resident night TOY TOY) and Truth do the all-night clubbing work of a fabric or Berghain.

For Black Coffee, the summer has been good. Now in its third year, he enthuses about the Hï residency reaching a point of “cruise control” – meaning he now knows what he’s doing, rather than any hint of complacency – while he and Themba are working on another brand named Deep In The City. All this, and he plans to develop and release his own bespoke mixer. From his perspective, however, few of his plans are about self-promotion; instead, he just wants to be a good influence.

“I hope so, man,” he sighs. “I really hope so. Doing this has put me in a position where I’m influential, and that’s not an easy thing. I can practise to be a DJ, and that means I get better, but you can’t practise being influential. Where do you start? Where do you stop? Just by playing music I have big control over the youth of the country, and it’s a huge ask, a big thing. There’s no school for influence.” Yet by setting the right example to others, Black Coffee is setting a generation of African, and South African artists on a similar journey of self sufficiency, optimism and creativity. Africa may not be a jungle, but when it comes to electronic music, it continues to grow and bloom.

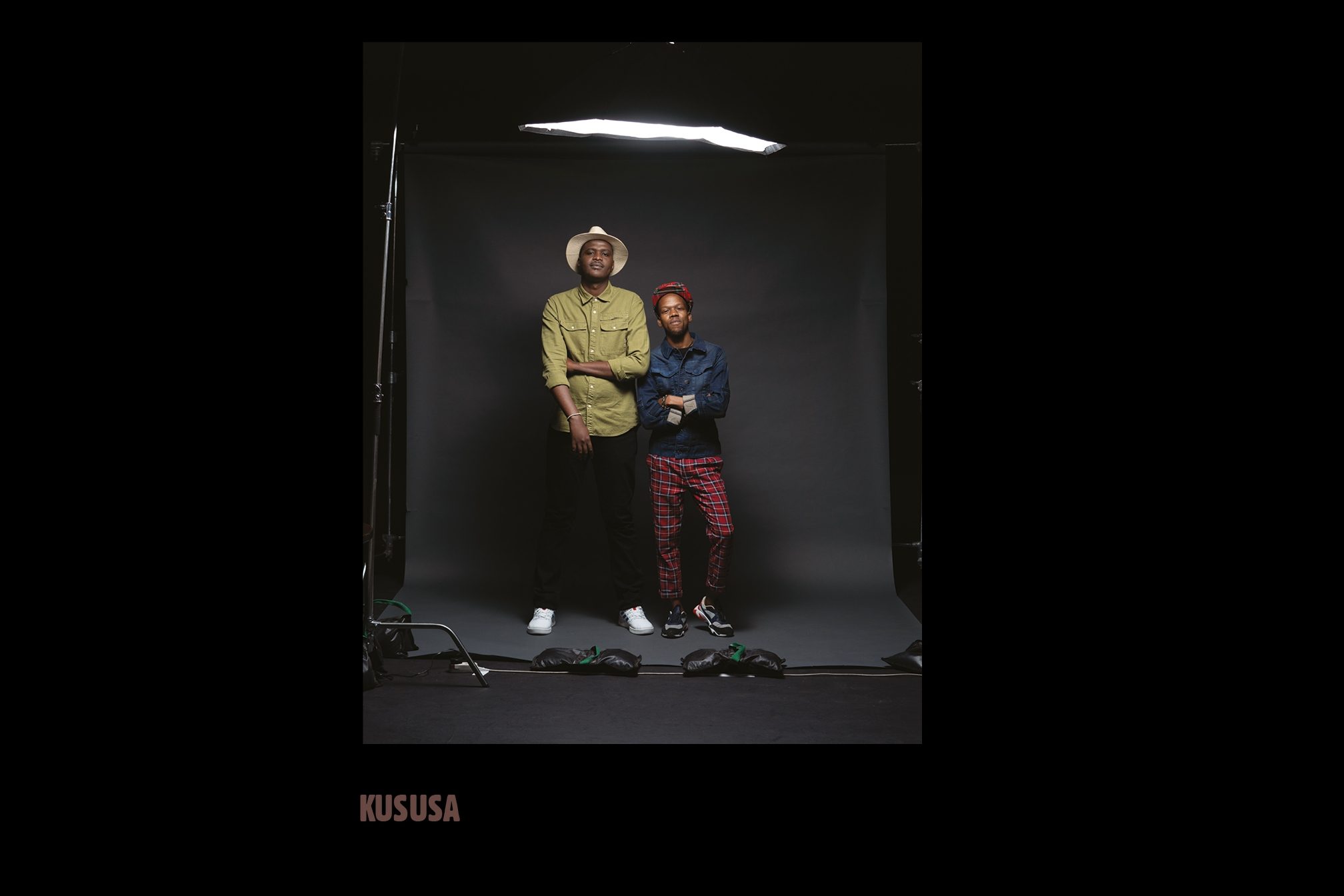

“He was my fan!” laughs Samurai Yasusa mischievously, recounting his first meeting with his producing partner Kunzima Theology at a gig in their home city of Durban in 2015. “I had a bigger brand than him before that – but when we met he was an extremely good DJ, I really liked how he played the music and the songs he was playing, and I couldn’t understand why he was just my fan. It was futuristic stuff, and when I listened to it I saw how we could complement each other.”

For Kunzima it was a case of right place, right time, and he dropped the suggestion to his more experienced collaborator. “He was like, ‘you know, I also do music’,” says Samurai, “so he sent me some of his projects, and he was doing lovely stuff. We started vibing about our own project, back and forward, and then we worked hard on making it a solid project together, rather than it being one-sided. In 2016 Kususa was born, and we’ve been making music ever since.”

The name ‘Kususa’, says Samurai, is both a fusion of the pair’s stage names (Samurai is Mncedi Tshicila; Kunzima is Joshua Sokweba) and a word which, when roughly translated into the South African language of Shona, means ‘to start over’. The pair’s first song together was a thundering 2017 remix, with QueTornik, of DeMajor’s ‘Traveller’. “That’s the track which I feel highlighted what we were going to do. It had all the right elements,” says Samurai.

What are the elements of a Kususa track? “A hard kick, right? And that African rhythm,” he says. “But for every track we just pick it up and go forward with it, every situation has its own energy, and that’s what I feel makes our sound very different. You’ll hear it’s all Kususa, but some will be more mellow and some will be more hard-hitting.” Their latest is the just-released ‘Incwadi Encane’, with fellow Durbanite Argento Dust, on the Ibiza-based Sudam Recordings. It’s another banger, with a soulful groove and a fierce beat.

Samurai’s eyes were opened to music by the classic compilations of SA-based labels Soul Candi and House Afrika, and was further informed by the Durban-born sound of gqom (“kind of like broken beat, but with synths and kicking bass,” he explains). Yet the pair’s roots go even deeper. “There’s a genre called maskanda, which is originally from KwaZulu-Natal,” he explains. “We feed from there, and some of the patterns are from Kenya and what-not, and we incorporate that with synths to make our sound. Imagine two guys, totally different from each other, and the stories they can tell – there are so many parts of our sound to explore.”

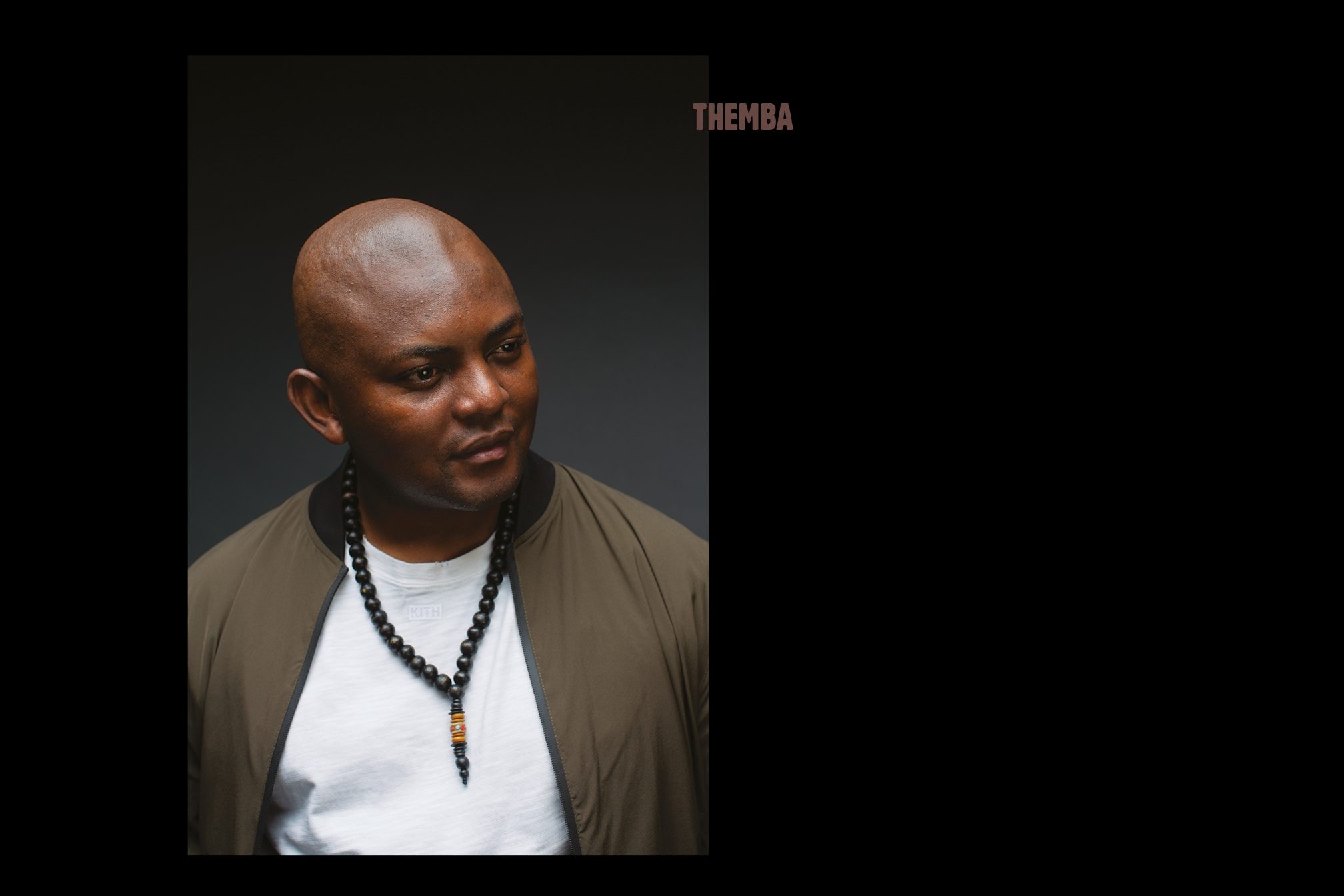

“I get it, man,” says Themba Nkosi with a laugh. “In any country, you can be a newcomer wherever you go.” As he waits on a sunny afternoon in Italy for his first ever date in the country, Themba has a philosophical response to being considered a ‘newcomer’ by the club industry in Europe when his career stretches back for two high-profile decades in South Africa.

Raved about as SA’s next hottest thing after Black Coffee when he released on Hot Since 82’s Knee Deep In Sound and on Yoshitoshi in 2018, this might have been to do with Themba’s personal rebranding using his own name. A DJ at some of Johannesburg’s biggest clubs during his university days at the turn of the century, it was as Euphonik that he became known for his radio mixes and scored a job as A&R at South Africa’s seminal dance label Soul Candi, putting together tracks for their compilations.

“I didn’t change myself, I focused on a specific audience and worked towards it,” says Themba, whose influence comes from his parents’ soul and jazz collection, the hip hop and kwaito of the ‘street bashes’ thrown by his cousin in the township of Daveyton (11-year-old Themba was only allowed to watch from the living room window), and the techno and electro listened to by classmates at the white school his parents sacrificed to send him to.

“To South Africans it doesn’t matter what you play, DJing is a very open format,” he continues. “In the rest of the world everyone wants to know what box you fit into, but where we come from that doesn’t exist. Our country’s very big on song and dance, especially with our apartheid history; the youth of South Africa like to use music against the bad things that happened in our country, so we dance a lot. Music is just a part of my life, as it is for South Africa.”

Newly returned from a three-date tour of America, and residing in Ibiza for the summer due to work, it makes sense that Themba is currently remixing the great Nigerian afrofuturist Fela Kuti; of all the fine DJs and producers on these pages, he is the one who most closely shares Black Coffee’s vision for South Africa as a future musical force. “At the moment I’m navigating through the scene and trying to do things the right way,” he says, “because if you know where we come from, then you understand that guys like myself and Black Coffee can’t [afford to] make mistakes.

“Every single move is important, considering the amount of people we have to give hope to back home. We come from a country where hope is our biggest commodity, so for somebody to see us do what we do, they know they can as well. At the same time, how do you operate at a level where you’re one hundred per cent yourself? It’s self-discovery – you need to find out who you are, what resonates with you and where you come from, and bring that to the rest of the world. The minute I understood that, the world opened up to me.”

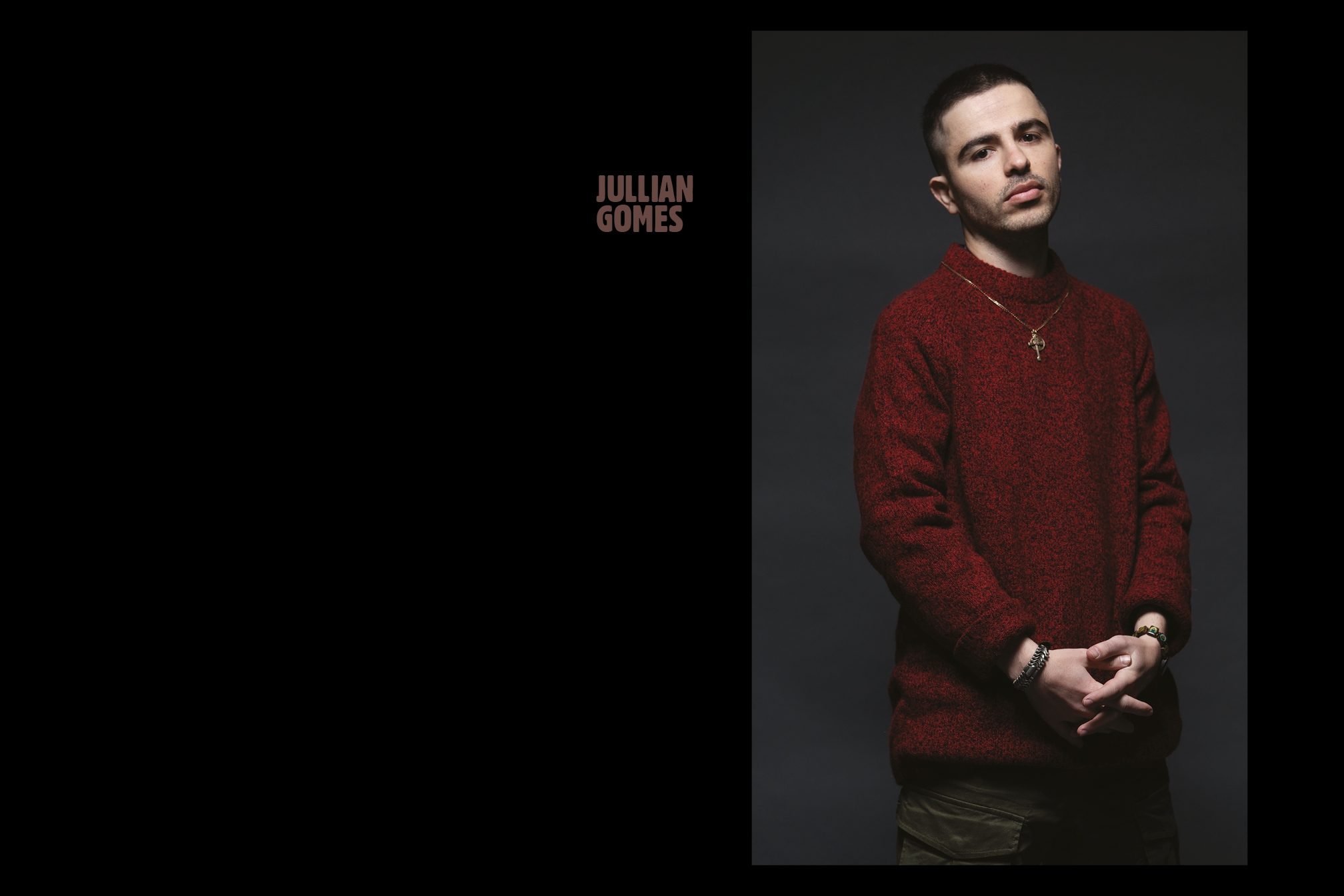

In the 1980s Jullian Gomes’ parents migrated from the Portuguese island of Madeira to Praetoria in South Africa, where they owned a bar and restaurant with DJs playing at the weekend. When apartheid fell in the 1990s and many white people left the area, Gomes’ family stuck around, and the racial and social barriers he saw fall away informed his life in music from then on.

“Every day after school my parents picked me up and took me to the bar, so I’d sit in the back room and do my homework,” recalls Gomes, whose earliest memory of music is the smell of his older cousin’s extensive record collection – among it Frankie Knuckles and Masters At Work. “There was a DJ at my parents’ work, and he was playing mostly Larry Heard, Black Box, Ten City, Inner City. I thought, ‘this is cool’. Every day I sold my lunch and bought records instead, newer ones like Innervisions stuff, early Âme.”

His parents’ club was where Gomes learned to DJ, taking his first turn when he was just 13. “My first gig I had to stand on crates to play,” he says. “I did my homework, then at night I DJed, and that’s how I built my reputation. Things had changed in the city, it was more of a black audience, and as a white guy

I learned a lot about soul and house music. It was amazing for me to start my career in that way. At 2:AM my dad would drop me home, then I would sleep and go to school. It was quite a start.”In 2007 he began a production collaboration with his cousin Michael named G.Family, which lasted for half a decade and brought low-key international releases on French producer Franck Rodger’s Real Tone label, and on Germany’s Foliage, which also released Black Coffee. The project ended in 2012, by which time Gomes had attended the Red Bull Music Academy in London in 2010 and had his eyes opened to an international scene that was also beginning to notice him.

His three album releases on Martin ‘Atjazz’ Iveson’s label includes the 2016 debut proper ‘Late Dreamer’, a lush homage to two classic styles, US house and South African midtempo, which is best compared to slowed-down UK garage. “The scene in South Africa is amazing, it’s one in a million and very different,” says the Johannesburg-based Gomes now. “There are a lot of stereotypes about African electronic music – about Africa generally – but there’s so much going on here.

“It’s true we’re a developing country, and we have problems that we’re well aware of, but the scene itself, and the experience of how people react to music in South Africa… it’s like a spiritual dance, the energy is on a whole other level. The love for house music is like no other place: you have to experience it.”

Had he been born on a different continent, perhaps Nicodimus Mogashoa would never have been a house music artist at all. “I was inspired by hip hop before house,” he recalls. “I grew up listening to it, because it was one of the big sounds across the globe. This was when West Coast hip hop was big. Dr Dre, Eminem… Dre was my favourite producer.”

His ambition, growing up in a small township in the north, was to be a rap producer. But then everything changed. “A couple of school friends introduced me to house music,” he says. “Every day they would talk about new tunes, and I was fascinated by their conversations. I realised that hip hop had its own groove, and that this [groove] was from America. But in South Africa we made house music our own. From realising that, I fell in love with it; I knew it was something that connected and united people – the opposite of hip hop, in many ways. Not much was happening in the township, I didn’t go out so much, but I was intrigued by technology, so I set out to create something.”

He puts his rise as a producer down to being born in the age of the internet, with tracks created in his bedroom. “I approached the producer Nick Holder online and he liked my sounds,” says Mogashoa. The Toronto-based Holder released his earliest recordings on his DNH label in 2012. “I became known internationally before I did in South Africa, and I would say that’s been an advantage.”

Da Capo has also recorded for Black Coffee’s label, and in 2018 his track ‘Afrika’ was remixed and released by Louie Vega. “Black Coffee is someone who has changed a lot of people’s lives, who has inspired a lot of people,” says Mogashoa. “He’s played a huge role in what I do today. I did a remix for Kato Change called ‘Abiro’; the lyrics are very traditional Kenyan lyrics, which people around the world don’t understand, but they still sing along because of how melodic it is. Black Coffee played it at Tomorrowland, and I found the response to it so emotional, so touching.”

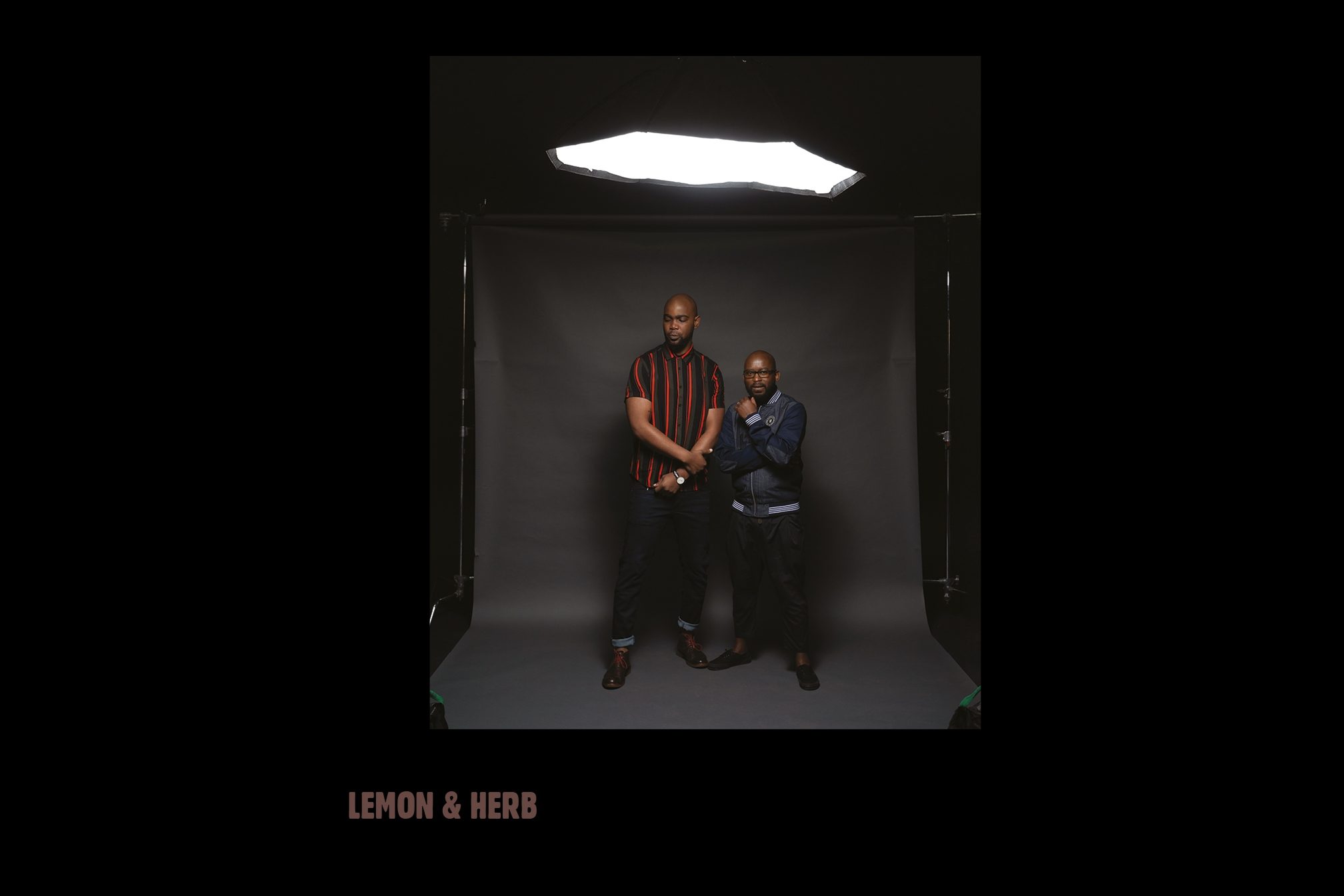

Like the flavours they’ve chosen for their name, Don Jobe and Skhumbuzo Radebe have always worked well together – ever since primary school, in fact. “Even then we had the same likes, the same creativity, in art classes and music classes,” says Jobe. “Then during our uni days, we got into house. In 2006 we started playing around with production software, and since then that’s what we’ve been doing.”

“Don played the keyboard in church, that’s his musical background,” explains Radebe. “We didn’t have any formal training, it was learning by ear. We’re just inquisitive people; during high school we used to attend talent shows, whether we were rapping, playing the piano, doing remixes of popular songs or singing. I grew up with a father who collected hip hop and Marvin Gaye, and my grandfather, who played in church as well, got me my first keyboard as a gift.”

The pair – who were a trio with Thamsanqa Ntintili until roughly a year ago – studied engineering at university and were influenced by the mixtape boom of the mid-2000s, especially the resurgence of kwaito. “It was the closest genre that made sense and felt relevant to me at a young age,” says Jobe. “We listened to the rap parts, yes, but the beats were the main thing. The sound was electronic, and compared to jazz or r’n’b, kwaito was a more electronic sound. We grew up with that.”

Lemon & Herb released their first music in 2010, and have since made a wider impression – for example, their well-named Uplifting mix of Atjazz & Robert Owens’ ‘Love Someone’ in 2010. Key tracks, say the pair, include the dreamy ‘Velani With Moonchild’ from 2015 album ‘Tomorrow In Detail’ and the moody afro-tech of last year’s ‘Ivory’, a hit when Black Coffee played it at Tomorrowland. That was an experiment, a reach for the new sound of electronic South Africa.

“Thinking about the way different countries experience music, in Africa I think there’s a swing to it,” says Radebe. “It’s not as direct and forthcoming [as European house], it’s almost laid-back, more, swaying back and forth… it’s hard to express it! But the only thing that might be on time is the kick of the song, if that makes sense?”

Even more than the sound, says Jobe, it’s the attitude. “I like the vibe of the artists Black Coffee is pushing in South Africa, in terms of communication and the relationships we’ve created. It’s all positive energy, it’s all about growth, it’s about expressing ourselves and spreading this music all over the world.”

One of the younger and less-heralded artists amid the current generation of South African producers getting ready to break out onto the international scene is also one who’s perfectly placed to follow the same journey taken by the most famous countryman in his field. Argento Dust – real name Minenhle Ndlazi – is from the township of Umlazi, near Durban, which was also home to Black Coffee before he worked his way to international stardom.

“I was inspired by people like Black Coffee and Culoe de Song,” says Ndlazi. “That’s where I started to love house music and pay attention to it. For me, this thing started in 2010. I’ve been in music for ten years – since I was in high school, still a learner.” House Junkies was his first project, as part of a quartet of friends from Umlazi who were studying production in Durban, though they went their separate ways in 2014 when all involved decided they wanted to try and make it on their own.

For Ndlazi, recognition came quickly. In 2015 he worked with DJ Shimza on ‘Congo Congo’, a rough-edged but commercial party track with a distinctive afro edge, which became a big club hit in South Africa and drew attention further afield. The pair met through social media, but the collaboration turned out so well that Ndlazi worked once more with Shimza on 2018’s ‘All Alone’, which had a similar mood. When Black Coffee created a mixtape for Sónar’s 25th anniversary last year, ‘All Alone’ was on it.

More recently, Ndlazi has collaborated with old friends Kususa, including on the lush groove of this summer’s ‘Incwadi Encane’. “They’ve been my friends for a long time,” says Ndlazi. “Kunzima lived in the same neighbourhood, so we’ve known each other for many years. We’ve got the same taste, because our music uses a mixture of African sounds and drums blended with techno. It’s all music combined, of very different types.”

For Ndlazi it’s more than just the ease of working with friends from the local area that brought him together with Kususa; instead, it’s something about where they’re from which sets them apart. “In Durban, I think it’s a culture,” he says. “We do what’s inside, we do what we love. That’s why we always come up with something different. Our music has its own taste: it’s different from other genres. To us, it’s cultural.”

David Pollock is a freelance writer, follow him on Twitter

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.