The Church of the Holy Communion has had many lives

The building is often identified by locals and tour guides as one of New York’s cursed spaces. Even before its 1980s heyday, the spot has been plagued by problems (financial, social, and otherwise) that have been the downfall of many a company trying to establish itself in the historic space. But looked at another way, the building is a time capsule. In its long history, you can follow the rise of the rave, the rehabilitation of the city, the popularity of the boutique fitness craze, and the trend toward atmosphere-centric dining.

And, as Angela Jia Kim, a former tenant of the space, points out, its history feels so unique to New York, and speaks to the city’s culture on a deep level. “It’s a church of contradictions,” she says. “To go from a place of worship to a place of sin to a marketplace to now a gym—it’s outrageous and creative. It embodies the idea that you can do anything here. That a church like that would go through so many lives—it’s just so New York.”

Take a look at this curious building’s origins—and all the very distinct ways in which it has changed over the past two centuries.

The Church of the Holy Communion was initially built in the mid-19th century, when Sixth Avenue was home to some of the wealthiest New Yorkers, like Horace Greeley, Edith Wharton, and even members of the Roosevelt family. This group was filled with devout churchgoers, as Anglican Catholicism was on the rise at the time (thanks to a well-to-do clergyman named William August Muhlenberg). Backed by the tremendous financial resources of the neighbourhood, the Church of the Holy Communion was constructed right on Sixth Avenue.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7556131/limelight_old_nypl.jpg)

Its architect, Richard Upjohn, designed several other Anglican churches in Manhattan, including Trinity Church on Wall Street and Madison Square Presbyterian Church, but according to architectural historian Francis Morrone, Upjohn intended for this building to really stand out. “All of [Upjohn’s] other churches were very symmetrical, very Gothic—they were trying very hard not to offend people,” he says. “The Church of the Holy Communion went a bit further. It sprawled all over the place. It was asymmetrical. It had rubbled stonework. It was like a country church.” Its silhouette remains one of Sixth Avenue’s most distinctive landmarks to this day.

For a century, the congregation grew at a rapid pace, but in the 1960s, as the area became more developed and the post-WWII religious boom fizzled out, residents started to move to other neighborhoods, or just stopped going to church altogether. The decision was made to consolidate the congregations of the area into a single church: St George’s.

But before the Church of the Holy Communion was deconsecrated, the building was designated a landmark by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission in 1966—a decision that has allowed it to, in spite of its many inhabitants, exist relatively unchanged. “It’s the last thing on Sixth Avenue that reminds us what that neighborhood was like when it was in its residential heyday,” Morrone says.

1976–1983: The $99 lease and attempted rehabilitation

In 1976, eager to earn some money off the now-empty church building, whose surrounding neighborhood had become riddled with crime, the parish granted a 99-year lease to the Lindisfarne Association, a research collective of artists, scientists, and scholars.

According to William Irwin Thompson, the organization’s founder, the city was going bankrupt at the time: “Every single foundation turned our funding applications down because they were in crisis mode to deal with the crack epidemic,” he says. “Social issues trumped intellectual programs.” A colleague advised Thompson to take a look at the Church of the Holy Communion, and eventually, he was able to strike an unbelievable deal with the parish: just a dollar a year to rent the space out.

For a little while, the Association became a veritable cultural center in the neighborhood, bringing in names such as Wendell Berry, Gary Snyder, John Michel, and Kathleen Raine to give lectures and do readings. Running a research association in the former church, however, proved difficult: Thompson recalls heat costs running up to $15,000 a year, as well as a few attempted break-ins, and a student getting raped on her way home from class.

After only two years in the space, the Association could no longer afford the operating costs, and the church went back into the hands of the parish. The parish turned around and sold the space to Odyssey House, a drug and alcohol rehabilitation center. In spite of the need and demand for such a spot (the city had a rampant drug problem at the time), the non-profit did not last for long, once again due to financial constraints. After a bidding war, Odyssey House sold the space to notorious nightclub impresario Peter Gatien. “We would have preferred to sell to a church,” Ben Walker, then executive director of Odyssey House told The New York Times in 1983. “But we had to go with the highest bidder. It was that or go bankrupt.”

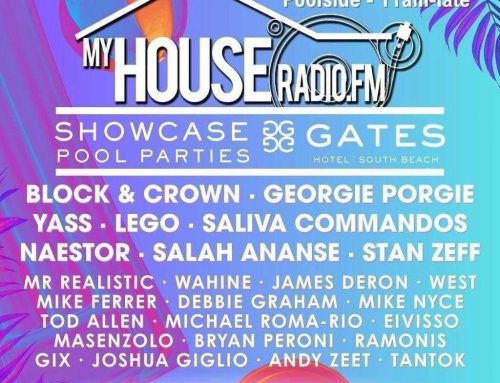

1983–2007: The most notorious club in New York

Despite many public proclamations against turning a religious space into a nightclub, Gatien charged ahead in creating the Limelight, which would become one of the most infamous party spaces in New York history. He turned the sisters’ house, right in the front area of the church, into the lobby, the chapel into a private lounge, and the main church into a giant dance floor—the entire renovation was said to have cost well into seven figures. “[Gatien] was looking to make a statement architecturally, and the church was a spectacular building,” says Frank Owen, author of Clubland: The Fabulous Rise and Murderous Fall of Club Culture. “In one of his previous clubs, he had a glass dance floor with sharks underneath it.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7561201/AP_840110051.jpg)

The opening night party on November 9, 1983 was hosted by none other than Andy Warhol, and the club went on to host several other noteworthy guests: Cyndi Lauper, Marilyn Manson, 50 Cent, members of Guns N’ Roses, and RuPaul, to name a few. It became one of New York’s hottest nightclubs, and the epicenter for rave culture in New York.

But after initially bringing in a slew of A-list guests, the club became primarily what Owen calls a “drug marketplace,” inviting in a lot of gangsters who profited heftily off of selling first ecstasy, then heroin. “I remember being on the balcony with Peter Gatien and saying, ‘This cannot go on anymore, this is going to end really badly,’” says Owen. “This was a place where drag queens were shoving Christmas lights up their butt, people were having sex all over the place, it was like the last days of the Roman Empire.”

Limelight’s depravity came to a head when the club’s notorious party promoter Michael Alig murdered and dismembered Angel Melendez, a regular drug dealer at Limelight. When Rudy Giuliani became mayor in 1994, he vowed to crack down on drugs and crime—particularly in light of the murder, which had made the club the subject of much scrutiny from the city government. Gatien was suspected of running a large drug ring in Limelight, leading to a massive investigation by the District Attorney’s office in 1996. After repeated closures by the city followed by several attempts by Gatien at reopening—including a rebrand under the name “The Avalon” in 2003, the legal bills proved insurmountable, and Gatien permanently closed the club in 2007.

By then, the surrounding neighborhood had greatly gentrified, and its new, more affluent tenants had turned against the club and its noisy inhabitants. As early as 1999, The Village Voice reported about the repeated attempts by the Flatiron Alliance (the area’s community group) to put the club out of business due to noise. According to Owen, it is, somewhat ironically, thanks to the Limelight that Chelsea became a hip neighborhood once again. Throughout Limelight’s heyday, he says, “Restaurants were starting to open. It was starting to feel like a real neighborhood again. So it was the very success of the Limelight that eventually killed it.”

2010–2014: A new shopping destination

A decade into the new century, Chelsea had become one of the trendier places to live, shop, and eat in Manhattan. Boutique owner Jack Menashe, along with designer James Mansour and creative director Melisca Klisanin, sought to transform the then-abandoned building into a three-story marketplace, intended to showcase up-and-coming artisanal brands.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7561625/5585734256_0c996182cb_o.jpg)

Angela Jia Kim, whose company, Savor Beauty, was one of Limelight Marketplace’s first tenants, says that while the space was a great initial test spot for her business, the church’s design was ultimately not conducive to a retail concept. “It had a very funky layout, which was a part of its appeal and its downfall,” she says, describing a maze-like format that made it very difficult for shoppers to get around.

The building’s landmark status prohibited vendors from placing significant signage outside the space, and many visitors to the marketplace weren’t all that interested in shopping. “We had so many passers-by who were just there to see the novelty of the space, and to tell us ‘I passed out here,’” says Kim. “Changing the concept of this big landmark,” which people still strongly associated with the debauchery of the Limelight nightclub, “it takes time,” Kim says.

Menashe tried retooling the concept, changing it to a department store simply called, “Limelight,” but it finally shuttered in 2014, leaving behind only a tiny outpost of Grimaldi’s (the pizza place’s first Manhattan location), which was seized and closed by the city this past August.

2014–Present: The spiritual workout and “vibe dining”

David Barton Gym, a brand known for its subversive marketing (“Look better naked” is one of its main slogans), announced in 2014 that it would be converting the Limelight space into its newest gym location. “The space had amazing synergy to the David Barton Gym brand,” says Kevin Kavanaugh, president of David Barton Gym. “[The brand] has a nightclub feel to it, so to have our gym in one of the most iconic buildings in New York City that was also previously a nightclub really appealed to us.”

The company has also gone through great lengths to pay homage to the church’s history: the original stained glass windows were restored, the disco balls from Limelight were hung up once again, and the ’80s newspaper wallpaper from the Limelight’s VIP area (now the men’s locker room) has been fully maintained.

“The space has always been part of the neighborhood and always will be,” says Kavanaugh. “To have people coming to the building to enhance their health is a nice way to contribute to the community and preserve the space.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7561349/limelight_7.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7561357/limelight_8.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7561365/limelight_15.jpg)

Meanwhile, the chapel (known as the “Shampoo Room” in Limelight’s heyday, home to many a foam party) has taken on several restaurant incarnations that have functioned separately from the main space: first, a short-lived French bistro called Chateau Cherbuliez, and now a modern dim sum restaurant called Jue Lan Club.

Stratis Morfogen, the restaurant’s owner, says he was initially attracted to the space because of his fond memories attending parties at the Limelight in the ’80s and ’90s. “I love the 19th-century architecture, the brick, the stained glass windows,” he explains. It was perfect for his restaurant’s focus on what he calls “vibe dining,” an experience made great by the surroundings as much as (or more than) by the food itself. The restaurant, like David Barton Gym, has leaned into the space’s past, with wallpaper made of photos from famous clubgoers and stately emerald green banquettes that feel like they would have fit in seamlessly at the Limelight.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.