Lots of things can go wrong when you spin with turntables, but what are clubs and DJs doing about them? We’ve got that and other articles for your weekend reading.

Why are problems with turntables in clubs so common? Gabriel Szatan goes deep on the issue and asks what can be done to solve this technical crisis.

How is this still happening so often? The potluck inconsistency of playing records in nightclubs has proven fatiguing enough to drive some, such as Lisa Smith, AKA recent RA podcaster Noncompliant, to swap formats after decades on turntables. That’s not uncommon. The proliferation of ever-more advanced DJ tools has led to more and more touring artists to leave the record bag at home. By now, turntables––for the sake of this piece, let’s assume the Technics SL-1200 model as the standard––have long since lost their hegemony in the booth. But they’re not yet an outmoded piece of kit. Whatever your take on the liberating qualities of digital DJing, surely no one should be punished for taking the classic approach. It simply shouldn’t be this stressful to play vinyl out, especially if you’re the one being paid to do so.

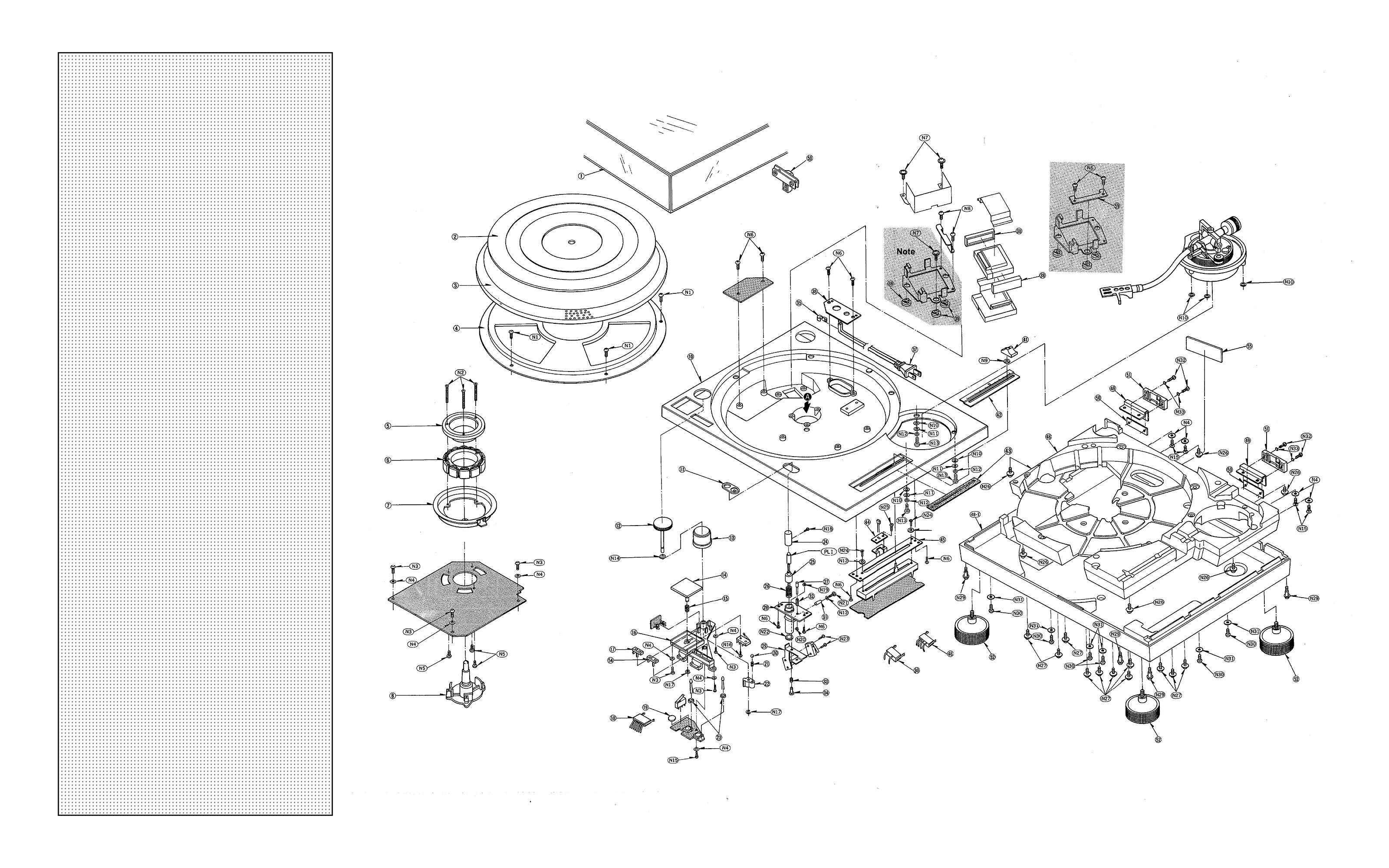

Even with a dependable reputation, Technics are pretty complicated beasts, prone to a fault like any mechanical device. Just about everything that can fuck up does fuck up at some point. When issues arise, they’re not as obvious as a frozen CDJ-2000 screen or a mixer outputting only the left channel. The tonearm and pitch slider is delicate enough that even a small amount of damage or dirt can prevent them from moving freely. It might not be immediately detectable to the eye, but it will become extremely obvious as the needle skips the groove, or the records fall out of time in the mix. As part of a club setup, this inherent fallibility is compounded by a litany of other variables in the heat of battle. Low visibility, misaligned monitors, unsteady bodies, spilled drinks and all manner of general carelessness come with the territory.

In her record-playing past, the most common issues for Smith included “wobbly tonearms, tonearms with mucked up connections to the cartridge, shitty needles, wonky pitch sliders, burned out light, feedback from improper isolation, and oh so much skipping.” For fellow scene lifer Jane Fitz, who remains steadfast in her decision to stick with records, a good gig is “when it’s not all of those at the same time––and you can add bouncing decks to the list, too.” There’s an especial irony in that. As Smith says: “The one thing you are there to make happen––dancing––is the one thing that will fuck you up the most.”

To play on turntables and expect a smooth ride every time is honestly a bit naive. Joseph Seaton (Call Super) and TJ Hertz (Objekt), known for being especially exacting when it comes to their setups, say that playing sketchy bars with shonky 1200s honed their skills. This is echoed by Jayne Connelly, best known as the drum & bass artist Storm. “When you start out standing up in front of the decks,” gritting your teeth and pushing through technical issues represents “half the art.” Nowadays, at least, there is a standardized setup in most clubs. Connelly tells of the early ’90s rave with her former DJ partner Khemistry where they were presented with arcane, off-brand decks, and MC Rage was forced to don a bright blue Binatone shoulder-strap radio mic. In spite of a contractual clause stipulating Technics, which would have allowed the duo to walk off stage, they gamely got on with the job.

Even when consciously trying to avoid slapstick scenarios in the dance, it’s hard to safeguard against every outcome. The Welsh festival Freerotation, which holds a gilded reputation for its consistency of hi-spec sound and hassle-free atmosphere, has many DJs playing vinyl each year. First aid kits with spare cartridges and needles are available at each of the five stages, with six backups on standby across the site, and yet more within reach from a trusted list of lenders. In spite of such rigorous planning, cofounder Steevio admits last year’s edition saw some minor record skipping on the outdoor stage due to unnoticed structural wear, while in earlier years, an indoor Soundsystem’s position “directly above a cellar with a suspended wooden floor” had been causing unwanted vibration. Isonoe isolators underneath all decks resolved that problem, and reinforced support for the outdoor stage should fix the new issue for 2018.

You’d think a proactive approach toward reliable sound would be the priority for any music event. It minimizes risk and frees you up for whatever else needs troubleshooting (there’s usually plenty). All being well, everyone goes home happy. Sadly, that remains far from reality. Hiccups are forgivable, but when the problem is so bad that it hurts a DJ’s performance, it can ruin the night for everyone. “At an annual festival unforeseen things can go wrong,” Steevio says. But “in a club there’s absolutely no excuse for it.” So why do excuses continue to be made?

The mechanisms of club culture often don’t correctly support record-playing artists. Pristine sound, after all, isn’t the rush most people chase every weekend. But that doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be prioritized. Across the globe, there’s a ballooning number of people who feed into the scene, but there’s a diminished number of people who can be routinely counted on. It’s an inverted ratio that makes no sense. This nebulous cloud of promoters, bookers, venue owners, sound techs and other peripheral figures need to be held accountable and do better.

The inexperienced, or those who simply half-arse their work, have a lot to answer for. Even the side of dance music that considers itself a less mainstream concern is, compared to earlier eras of club culture, an exceptionally well-oiled machine in 2018. It doesn’t require your own sound system, a standout space, or a sizeable investment to throw a night—or even a small festival if you have the means and the willpower. But too often it all falls down in the precision required for playing records, something frequently overlooked when renting in external sound on a budget.

From a UK perspective, Fitz thinks the problem is getting worse. “You have more events in cafes and warehouses and basements, places that aren’t really meant to have parties,” she says. “Often run by a lot of enthusiastic young people with unfortunately very little knowledge or experience of how to set anything up right, and faith in older sound guys who will happily humiliate them into believing they should be trusted!” What aggravates the issue, according to Hertz, is when these already iffy multi-purpose spaces are then sloppily rigged up. “Countless times I used to show up to a soundcheck to find the turntables placed on a table on a big bouncy stage with enough vibration coming through the floor to make your stomach churn, and the sound engineer would hand me a bit of sponge saying, ‘Here, this should fix the feedback.'” Picking the wrong sound hire company for a one-off party can be a major tripwire.

But a DIY spirit and lack of a fixed home needn’t be a limiter. For Aaron Clark, who has co-run the Humanaut, Honcho and Hot Mass parties out of Pittsburgh over the past 15 years, “a paid audio technician is a luxury dream.” His solution is pretty simple: it comes down to diligence and due care and building a network of people around you to lend resources and help steer the ship in a bind. With at least half of Hot Mass guests playing records in an after-hours space that often becomes a sweatbox, “the primary responsibility is on us. We all have to wear that hat collectively. Everyone who plays records knows what it’s like to be excited about a gig,” and then have their mood demolished by something avoidable going awry.

As obvious as it might sound, a commonly skipped step is putting aside additional cover. Spare needles, cartridges, and leads are one thing, but having a replacement ready to rock on a minute’s notice should also be standard practice. Jose Alberto Luna, the current production manager at Chicago’s smart bar, is unwavering on this. “No proper club or underground event should ever, ever have any less,” he says. At smart bar they currently have eight fully serviced Technics SL-1200s under the club’s roof. Spending just enough to cover the basics and praying nothing goes wrong doesn’t cut it.

Whether semi-legal or fully licensed, those interviewed for this piece seemed to agree that small-to-midsize events are often the most reliable. Second nature in Seattle, Breakfast Club in Tel Aviv, Pickle Factory in London, Rural festival in Japan, plus Dekmantel and Secretsundaze events worldwide got specific nods. Hertz, who dutifully spends time in advance sound-checking nearly every gig he plays, feels this tier are often the most amenable to his requests. Within an already small pool of vinyl DJs, “it’s a doubly slim minority who would be exacting enough to demand that they be able to play the quietest 7-inch at the highest volume without feedback—most just rock up, play some loud-cut techno 12 inches, and if there’s a bit of feedback, then, whatever. So I’m endlessly grateful to independent promoters who have to go pick up these 30kg slabs of rock at their local garden centre on the day of the show to put my neurotic mind at ease.”

When it’s not to do with inexperience, improper provisions can centre on finance, or a lack thereof. “Most clubs don’t have people paid to spend their lives dedicated to looking after this stuff,” says Seaton. “It just isn’t feasible for small/mid-sized clubs in many cases.” That rings true. If you’re fighting to stay in the black, spinning multiple plates with little assistance for a night with a razor-thin margin of error, you are probably more likely to put below par equipment in front of your DJs.

It becomes a more severe problem when those with the means to provide proper sound support fail to do so. And the glare becomes harsher still when superfluous accessories are taken care of, or multiple acts are crammed into a limited run time, but something as simple as a stable surface for decks isn’t.

One of the most common gripes about this current era of clubbing is that the experiential nature of dance music, in ever more audacious settings, detracts from the actual experience of enjoying music. Even when booking non-commercial artists, mid-to-large size venues in second-tier cities feel compelled to punch upwards toward grandiosity in order to run the race. Weighing a bill down with more names than necessary to try and lure punters is one problem; often the early acts are loss-leaders, playing to no one or acting as martyrs for technical kinks that get ironed out by the time the headliner steps up. Yet there’s no valour in seeing a DJ backed by their name in 40-foot lights, but with a face like thunder as records skip and volume fluctuates.

While zooming ahead to create advanced infrastructure that supports a circuit for touring DJs, the industry has left behind the value of sufficient audio care. The scene has become imbalanced. I’m inclined to believe that a congested international promoter field has worsened this technical blind spot. The issue goes beyond turntables: monitoring is also a major bugbear. Both of these are demonstrably more likely to be sacrificed if you’re scuttling the headliner into the booth with mere minutes to go before their set. At peak times in the calendar––the height of summer festival season, say––when DJs power through numerous bookings in one go on a single trip, often haring between national borders to make it happen, careless mistakes are bound to increase.

While chatting with a friend who worked on the recent Mastermix event at Warehouse Project, he mentioned the main room setup had numerous linked CDJs and mixers, plus two turntables––but the latter part seemingly existing only for show. This doesn’t strike me as odd. Why would, say, Hunee or Jackmaster, even as outspoken vinyl aficionados with the technical chops to pull off a great set solely on wax, flit between potentially temperamental formats? It must be an insane stress to suss out the cause of airborne feedback or swap dirty needles, while simultaneously reading the mood of a huge audience and catering selections for them. Why risk it? This becomes a self-perpetuating motion machine: apprehension from the DJ reduces their likelihood to play records in a high-profile setting, which entrenches the club or festival’s decision to phase out turntables as a first option, and so on. It affords an excuse for the supply side of the chain to narrow what they provide, and flattens the landscape. “The freedom of which format you’d like to use,” Connelly says, “has been slowly but surely taken away from the DJ.”

If this problem has become structural, the actors within it all play their roles. The globalized club scene isn’t going anywhere soon, nor will advancements in digital DJ hardware suddenly go into reverse. Does part of the onus rest on those who continue lugging about their record bags, while also consciously operating within a system that makes this difficult? Could problems be avoided on their part by forgoing a lavish promoter-expensed dinner to get a proper soundcheck in, or point-blank reject gigs where they’ll be rushed on and off a festival stage? Should they come more ready for battle?

Vinyl DJs have accumulated some useful personal tips over the years: spend a few minutes cleaning records before a show, and push hard for a soundcheck, no matter what, says Connelly. Smith says that, as a former Serato user, activating the “Instant Doubles” option and mixing partly through her laptop interface got her out of jail when down to only one functioning turntable. Seaton and Hertz say that even something as simple as riding the pitch up and down, hitting the 33/45 RPM buttons, or methodologically going piece by piece along the signal chain, from stylus to cables, are handy troubleshooting options.

“I’m of the opinion that it’s not my job to clean up other people’s mess,” says Fitz. She carries USBs as a last resort, but often disguises the fact she has a back-up, “because I want to highlight how poor their setup is, and how incompetent or simply indifferent the sound technician or promoter actually is to either the DJ or their ticket-paying punters.” Later in our email conversation, she adds a caveat: “I actually feel sorry for a lot of sound techs because you’ll have a conversation and they’ll be like, ‘Well I know this is shit, but the owner doesn’t care, so I can’t really do anything about it.'”

If you’re hired specifically to assist with audio-related issues, shouldn’t you be on top of it when something flares up? Yes and no. There are some useless or arrogant people in this field. As an almost exclusively male profession, there are a disappointing number of sexist ones, too—Nabihah Iqbal and The Black Madonna, among others, made public comments last year about being disrespected by stage hands on account of their gender. Fitz and Connelly brought up similar stories, but wanted to tamp down the issue by taking an even-handed approach to it.

This is indicative of a broader sentiment toward sound engineers: sympathy, rather than scorn. “Many lack the requisite experience to troubleshoot more obscure turntable issues,” says Hertz, “and can you blame them, given that most DJs have now been digital-only for longer than your average sound engineer’s career to date?” Seaton agrees: “I’ve had no end of abuse and suspicion from people who generally are at a fairly rough point in the general scheme of life. It’s not a particularly fun job being a sound person so I generally accept their abuse as a necessity for them to vent. I generally just keep my expectations low and try to make the best of things.”

When things are falling apart, is there anything you can do as an audience member? As strong as your compulsion to help out might be, there is one thing everyone I spoke with agreed on: don’t be a hero. “You think you may be helping,” says Clark, “but you likely aren’t. I remember one time we had an issue, four random partygoers just started trying to rewire things, unsolicited. Two people were pulling on the same cable from opposite ends without realizing it. It was like the nightclub Lady And The Tramp.”

Crises of this nature shouldn’t be taking place anyway. Ultimately, the buck has to stop with that nebulous cloud I mentioned earlier: the managers, owners, promoters and bookers who continue to over-stuff clubs and festivals without ensuring adequate sound. Professionalism begins at the top. Sending in an under-equipped sound tech for a big event doesn’t absolve you from responsibility. It’s an extension of endemic laziness.

The clubbing industry at large has lopsided priorities. There is a natural pecking order with everything it requires to keep a club solvent and successful, but those holding the purse strings too often get blindsided by solely looking out for the bottom line. No legitimate club forgets to take the right amount of money on the door, or forgets to make sure their alcohol license is still up to date, but many fall desperately short on the side that is the load-bearing pillar of a good night out: the sound. “People come out for the music. If you jeopardise that, you jeopardise it all,” Luna says.

But this problem can’t just be laid at the door of flashy big league club spaces and over-congested festivals. Objekt, Storm, Noncompliant, Call Super and Jane Fitz are all highly-respected DJs with international touring schedules, playing a variety of venues, big and small. Yet when asked to ballpark an overall figure of gigs where sound problems happen, the responses range from a minimum of 25%, up through 40-60%, and topping 75% for one. That is ludicrous. Can you imagine a clubbing landscape where half of venues leave a ticket list unprinted, or forget to stock the fridges? It’s a surprise more artists haven’t given up playing records entirely by this point.

A corrective course is sorely needed. The bottom line should be this: at whatever level you operate at, if you book a DJ to perform, you should make sure they’re able to give the absolute best account of themselves. Whether that’s putting more money into turntable servicing, more care into maintaining the equipment you have, more diligence in making sure your venue staff are up to scratch, more effort making friends you can fall back on in a pinch, or simply thinking twice about lugging a soundsystem into that enticing abandoned factory, it’s worth the time taken.

Though I understand the reticence to call out clubs or promoters with a bad track record (all eight interviewees politely waived the option to name names), I would suggest that being more vocal on this issue could help engender a positive change. As long as turntables remain a relevant format, the industry needs to improve its attitude in re-normalising their use. There is a direct link between a high quality of sound and a high quality of experience on nights out. This seems like something especially worth going to bat for.

As Smith summarises, “If the entertainment for the night has to struggle, it ruins it for everyone. When the setup is right, and the sound is right, then everyone wins.” Steevio drives the point home harder: “If you’re going to cut corners, the sound, equipment and crew are not where you should be doing it. The sound and quality of equipment is sacrosanct, and if you can’t get that right, you shouldn’t be organising events or working as tech at all.”

Ultimately, when it comes to running an event, the same mantra applies to the signal chain of a turntable as to running the night itself: you’re only as strong as your weakest link.

Objekt and Jose Alberto Luna, the production manager from smartbar, have shared their personal guidelines for troubleshooting turntables, which you can find here.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.