Over a career spanning four decades, the pioneering DJ Paul ‘Trouble’ Anderson, who has passed away after a long fight with cancer, could claim to have been at the forefront of most of the significant shifts in UK club culture. From the youth clubs and soul scene of the seventies right through to the global dance music festivals of today, Anderson was there at every turn. Clubs, roller discos, sound systems, warehouse parties, orbital raves, super clubs, Anderson did them all and usually first.

Indeed, this knack for being where the action remained with him until the end. Fittingly, one of Paul’s last DJ residencies was at Peckham’s Bussey Building, where over the five years he played there, the south-east London district rose from backwater to cultural and nightlife hotspot: with yet another generation young London club-goers falling under his spell in the process.

Born in 1959, Paul was one of six siblings, born to parents who had moved to Britain from Jamaica. Complications at home would see Paul spend much of his childhood in care being moved around care homes and foster families across England. This experience saw Paul effectively bringing himself up no doubt played its part in instilling the drive and single-mindedness that would propel Paul’s career and the need to make something of himself in his chosen field.

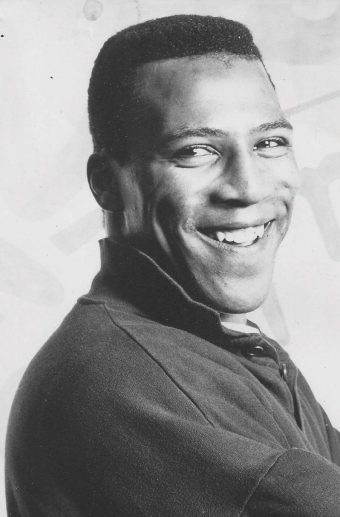

As a student, Paul did well enough at his studies to pass the eleven plus exam and gain a place at a grammar school. However, it was at sports that he would excel with his ability at football such that he was on the books with a variety of London football clubs during his youth. While physical activity would remain a passion throughout his life, it would take a second place to his first love, music.

Starting as a pop fan, by his teenage years, Paul favored the reggae and American soul and funk records that he heard and brought himself to the youth clubs of the early seventies. His growing interest in music and records encouraged by an Uncle who ran a reggae sound system which Paul would help out with, providing him with his first exposure to the art of DJ’ing.

When he was old enough to start going to clubs, it was as a dancer rather than a DJ that Paul would initially make his mark.

A small but thriving soul music club scene emerged in London’s surrounding home counties over this period, but black teenagers such as Paul found themselves all too often shut out of these venues by racist door policies. They turned instead to London’s West End and in particular a new club called Crackers which opened in 1974 and welcomed their custom. The club’s resident DJ Mark Roman programmed the latest imported American funk and soul to a crowd that was mixed in every way possible: black and white, gay and straight. As cutting edge in its fashions as it was with its music, the Crackers dance floor would pioneer many of the looks later associated with punk, and its alumni would go on to dominate the London club, music and fashion industries over the following decade.

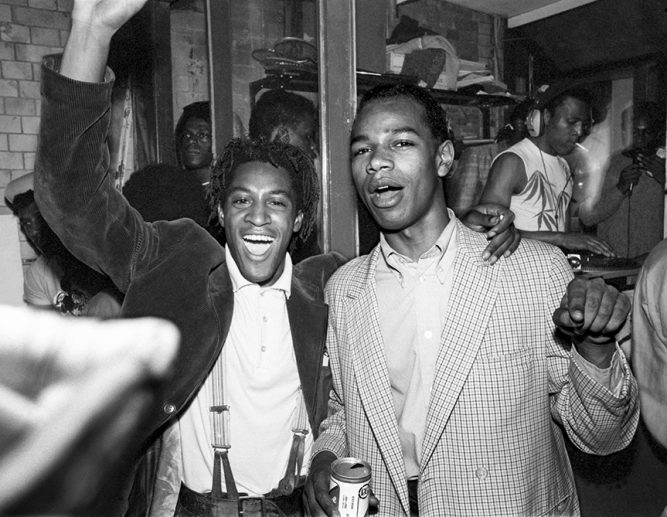

However, the real stars of Cracker’s were not fashionistas but rather a small band of young dancers who dominated the club’s dancefloor and included amongst their number a young Paul Anderson. When George Power, a flamboyant DJ of Greek Cypriot descent took over at Crackers, as an outsider himself, he immediately saw, the importance of cultivating and promoting Cracker’s dancefloor elite. To this end, he offered Paul the chance to move from the dancefloor to behind record decks, and in 1979 Paul’s DJ career was born.

At a time when the category of young black British DJ barely existed this was a significant development. Outside of the West End, the soul scene was a closed shop, dominated by a self-proclaimed ‘soul mafia’ of mostly older white DJs. With Paul Anderson’s elevation to the decks, for the first time, the crowd looked to the DJ booth and truly saw one of their own. A genie was out of its bottle, and a generation of young black Londoners took note.

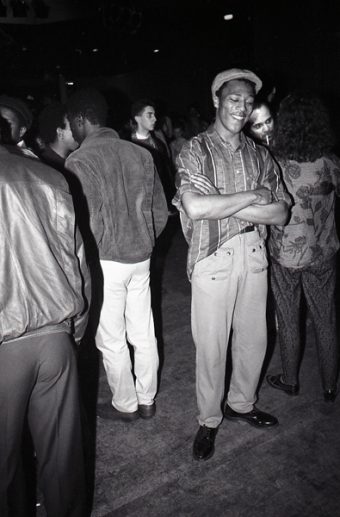

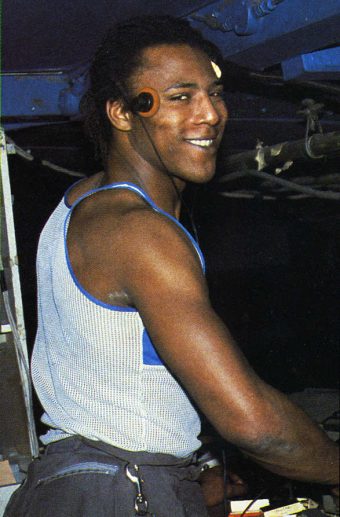

Bringing the streetwise swagger and showmanship of the dancefloor to the DJ booth, Paul would think nothing of jumping from behind the decks to take to the dance floor while the record he selected played. Even behind the decks, Paul would dance: for most DJ’s the dancefloor ended at the DJ booth for Paul it started there.

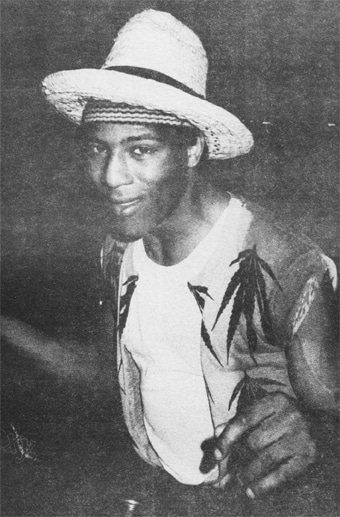

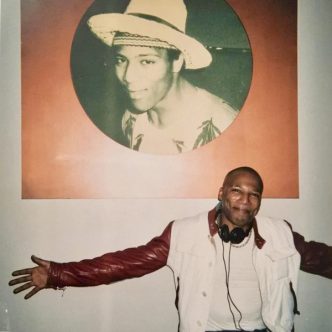

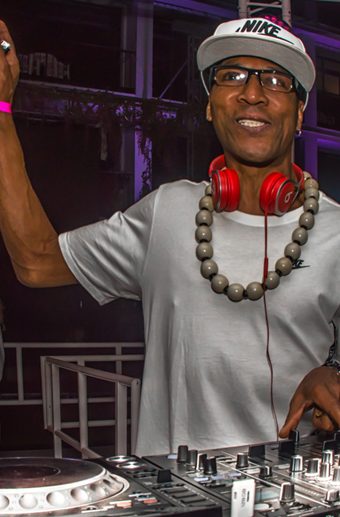

Naturally vain and fastidious about his appearance, in general, Paul realised instinctively that the way he presented himself was also part of what he could offer. In his early years choosing cut down t-shirts and vests that emphasised his athletic physique. This early form of self-branding never left him, and in his last decade, he cultivated a new look with colourful suits and hats making him immediately recognisable.

Paul’s career soon broadened beyond Crackers, and he got work playing disco and jazz-funk at other key venues such as Ronnie Scott’s and Global Village. Paul would also be both participant and DJ in London’s short-lived roller-disco boom playing at London’s first roller disco at Paddington’s Starlight Rooms. However, it was at another George Power venture that Paul would make his mark and cement his place in London clubland folklore.

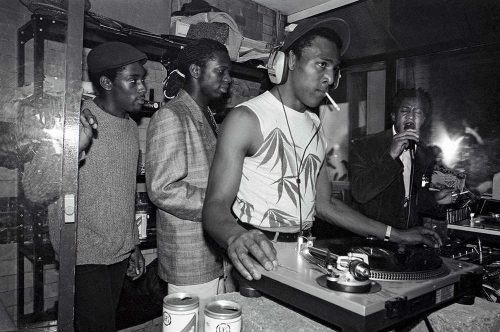

Jazzi-Funk opened at Camden’s Electric Ballroom in 1982. By now hip-hop culture had made its way across the Atlantic with breakdancing and body popping the latest craze for the London’s teenagers. The music in clubs changed accordingly, and the new electro and hip-hop records that emerged demanded a unique style of DJ’ing with scratching, cutting and mixing offering new possibilities to DJs. Paul had already dabbled with mixing and was quick to rise to the challenge.

It was perhaps unsurprising that Paul would excel at mixing: introducing as it did a physical dimension to the art of DJ’ing. With a natural gift for any physical activity, Paul approached mixing with the same confidence and single-mindedness he did football and dancing before it. There were skills to be learnt, practice to done and finally a performance to be given. His competitive nature meaning it wasn’t just enough to learn to mix – he had to beat the competition and be the best.

His mastery of this new skill and his eclectic electro sets electrified the crowd at Electric Ballroom and gave a distinctly British edge to this new American style. Paul was a hometown hero and role model. It is no exaggeration to say his nights at the Electric Ballroom launched a thousand DJ careers with

Around this time, Paul also launched his sound system and gained his nickname ‘Trouble’. A new breed of soul-based systems emerged such as Rap-a-Attack, Mastermind, Winner Roadshow, Good Times and Soul II Soul. Paul convinced his Uncle to let him transform his reggae sound system and chose the name Trouble Funk after his favourite Washington Go-Go band. From that point on he was known as Paul ‘Trouble’ Anderson.

Never confining himself to one scene or genre, Paul maintained his presence in the West End playing at the newly fashionable warehouse parties and becoming resident at the trendy mixed gay night The Lift at London’s Embassy Club. When a craze for old seventies funk emerged, Paul dusted off his crate of old youth club singles and was one of the residents at The Cat in the Hat, the home of London’s soon to be huge ‘rare groove’ craze.

A new dimension was added to his career when 1985 he was asked to join a new pirate radio station Kiss FM which sought to capitalise on this varied and growing dance scene. Launched by George Power and two of Anderson’s old Crackers friends Gordon Mac and Tosca.

Anderson was at the time playing a Sunday night residency with Mac at Kisses in Peckham, and, as at this club, Paul used his radio show to dip back into a style of post-disco dance music he’d championed at Crackers then the Electric Ballroom calling it ‘boogie’. This style that had evolved and lived on in the production of revered New York producers like Leroy Burgess and Patrick Adams. As a dancer, Paul had been an original boogie boy, and over the years this was perhaps the music closest to his heart. Indeed, if one was forced to choose just one Paul Anderson anthem, it would probably be Leroy Burgess’s production of the Universal Robot Band’s Barely Breaking Even. Paul’s boogie orientated sets helped expose this music to a new audience amongst the young rare groove crowd who flocked to nights like Dance Wicked.

However, it wasn’t going to boogie that was going to write the next chapter in Paul’s career but house music, an electronic four to the floor style that had emerged out of Chicago and had found a ready home in the UK. It had been bubbling in London for a couple of years but was set to explode in London with the acid house. Paul was no stranger to house and saw it for what it was, a modern update on the disco he’d played at Crackers and an extension of the electronic dance production styles he pioneered at the Electric Ballroom.

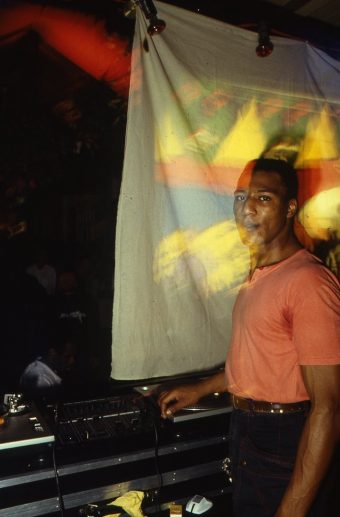

In the summer of 1988, as the rest of London went acid house, Paul became resident DJ and host of Kiss FM’s new Second Base club night at Dingwalls in London’s Camden Lock. Here he reloaded and polished his mixing skills and playing upfront from hip-hop to house. Instead of the acid sound, Paul zeroed in on the records coming out of New York and New Jersey which people were categorising as ‘garage’ after the famed NY club Paradise Garage. Songs like Adeva’s Respect, Paul Simpson’s Musical Freedom, and Phase II’s Reachin’.

This music was an inspiration for Paul to reinvent his Kiss FM radio show as a two-hour mix show Paul Anderson In the Mix. Like a scientist in a laboratory, during the day Paul began experimenting mixing these new records in with old disco records from his Crackers days such as Coffee’s Casanova and the Disco Dub Band’s For the Love of Money. Creating ever more complex multi-layered arrangements using a cassette deck, he realised that he could re-edit tracks the way he wanted them to be and create new track entirely by mixing elements of different tracks together. Paul’s mix show would on Kiss run for the next decade and take his audience onto another level.

Both on radio and in person, Paul’s style of mixing was that of a dancer he matched absolute precision with aggression cutting between tracks to give the mix a bump of energy as tracks transitioned rather than a smooth transition. His style was highly individual and immediately recognisable.

Re-invigorated, Paul was soon in demand London at fashionable London clubs such as Love at The Wag, MFI at Legends, Enter the Dragon in Kensington and an uber-hip Sunday night gig called Solaris.

By 1989 the first of the big orbital warehouse parties began to happen in fields and sheds around London’s M25. A strange mix of Acid House idealism and shady business, events like Sunrise and Biology could draw crowds of up to 10 000 people but were looked down on the Acid House elite and established and West End DJ’s refused to play at them. Never one to deny a crowd, Paul had no such reservations, and his musical mix was perfectly suited to the new generation. He had always kept up-tempo dance floor friendly hip-hop in his set and was a big fan of the hip-house when it emerged and was thus ahead of the curve as a hip-hop influence mixed with euphoric house fused would eventually fuse to create a new distinctly British dance sound.

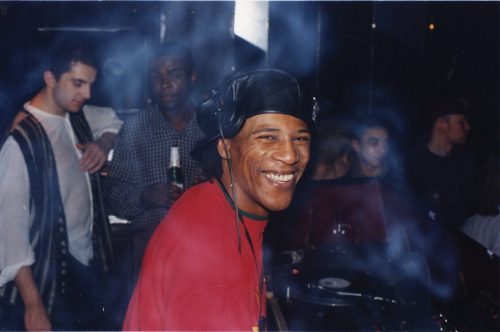

Paul had also developed a new look with a baseball cap, tracksuits bum bag and Nike Air Jordan’s ever-present on his feet. Arriving at a rave at 5.00am to dazzle the crowd, Paul cut a figure of the ultimate bad boy DJ, and the ‘Trouble’ legend was made anew for another generation. The raves also created a new generation of young DJ’s that enjoyed overnight success and huge followings. While names like Fabio, Grooverider, Colin Dale and Jumpin’ Jack Frost might have been new to other Paul knew most of these young DJs as teenage followers of his at Crackers and the Electric Ballroom. Paul’s trailblazing ten years earlier had finally born fruit with a whole new generation of young black British DJ’s who would go onto innovate entirely new genres of British dance music over the coming years.

In 1990 Kiss FM gained a license and began to broadcast legally across London and the surrounding areas. Paul was given pride of place in the schedule presenting his Paul Anderson’s Advanced Dance mix show at 9.00pm every Saturday night. This show would run for the next eight years and would become an institution as young London accompanied their pre-clubbing rituals to sounds of Paul’s mixing and his ‘Trouble in the mix’ jingles and gruff vocal interjections: the catchphrase ‘Thumpin’’ being a particular fan favourite.

As the 90s kicked in dance music went developed from a scene to an industry. In 1991 the Ministry of Sound opened in London’s Elephant and Castle area and was the first ‘super club’, and there was soon a nationwide network of large clubs. There were dance radio stations around the country, magazines like Mix-Mag and DJ Magazine and dance departments in all the major record companies.

One effect of this growth was that the dance industry could support a number of different sub-scenes and increasingly fragmented. The young teenage rave crowd going in one direction with ‘hardcore’, while the older clubbers stayed with classic house music and particularly the New York style, Garage. Specialist Garage nights such as Garage City run by Paul’s Kiss FM colleagues and acolytes, Bobby and Steve sprung up and was followed by others. The draw of these and the Ministry of Sound attracted New York DJ’s to the UK in ever bigger numbers with names like Tony Humphries, David Morales and Masters at Work regulars on the bill. Garage developed into a transatlantic business.

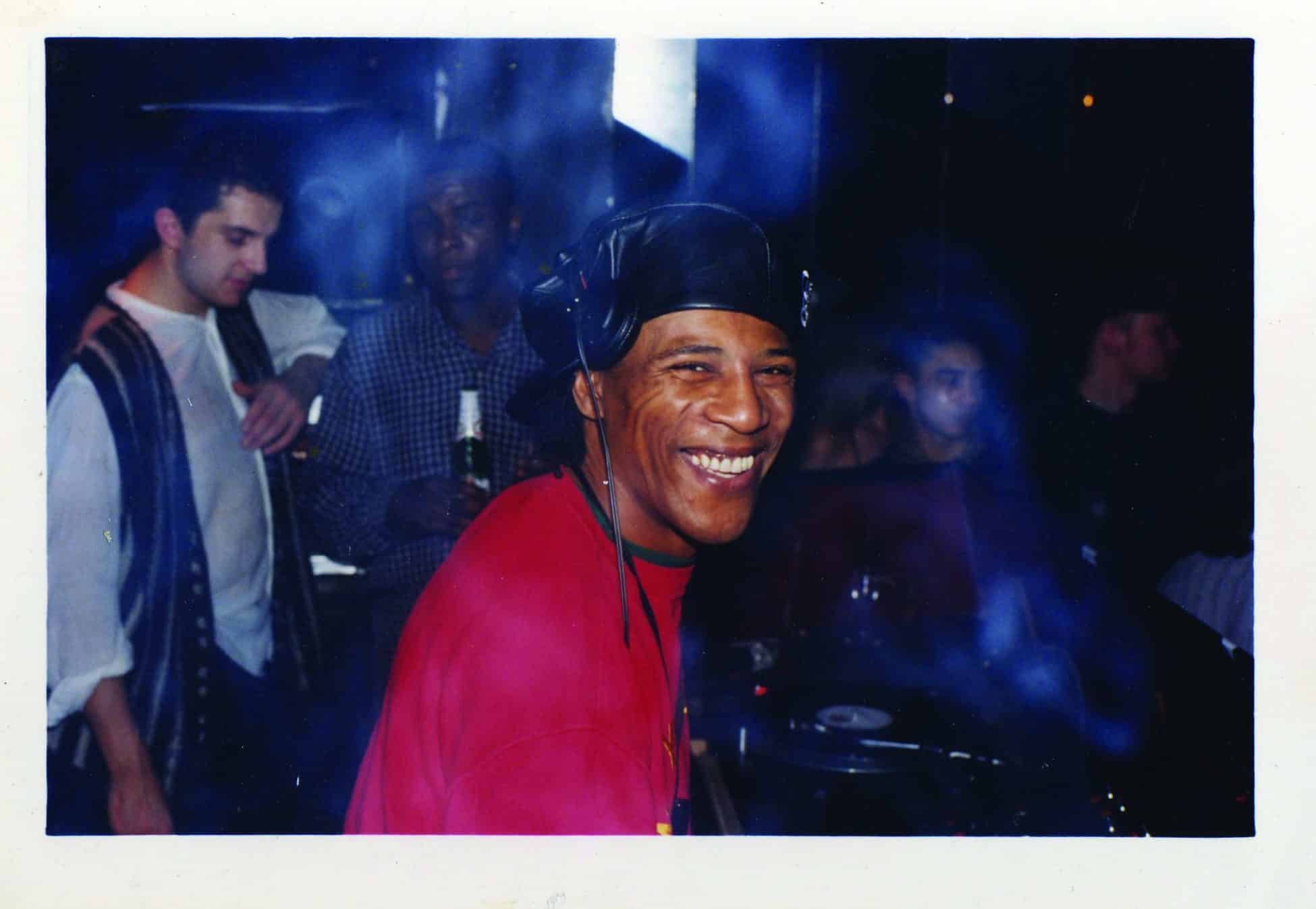

Although always suspicious of labels (‘House is where you live, Garage is where you park your car,’ he would quip), Paul was recognised as the undoubted Godfather of the UK’s garage scene respected by both its UK and American wing in equal amount and it was his reputation and popularity in this world allowed him to fulfil one of his longstanding ambitions when he set up his own night The Loft in 1992.

The Loft opened at the HQ Club, a converted wine bar in Camden Lock. Running on Wednesday nights, this club provided Paul with the live equivalent of his mix show, a platform which he controlled where he could truly present himself in the way he wanted. A long thin room with white walls, Paul’s decks would be set up at one end on a small stage, and he would look over the audience like a flock delivering a weekly musical sermon. It would soon be a sweatbox and Paul in his vest and dungarees would lead the way as ever. The stars of the US would come to pay homage and hang out with veteran divas such as Barbara Tucker, Jean Carne, Jocelyn Brown and Loleatta Holloway giving impromptu performances from the stage. For Paul things had truly turned a full circle with singers whose records had been in his box when he had started out now playing at his club. Over the decade it ran the Loft became an institution packed each week and only closing n 2002 because the HQ building was to be demolished.

The longevity of the Loft highlighted a change in dance music and clubbing as it entered the new millennium, dance music was now truly cross-generational in its appeal. At the Loft twenty-somethings who were just discovering Paul and his music danced next to middle age veterans of the London club scene to Paul’s music. The style of music that Paul played now being described as ‘soulful house’ was open to all ages and clubbers no longer had to hang up their dancing shoes as they entered middle age. New events catered to this older audience with mini-festivals dance festivals held in foreign beach resorts becoming increasingly popular. Paul would be a headliner at these events playing in Croatia, Antigua, What was missing was a radio station which reflected and catered to this demographic.

In 2012 original Kiss FM founder Gordon Mac rectified this situation when he launched Mi-Soul Radio at first as an internet radio and then a digital radio station which drew together all the elements of soul-based music new and old from the last four decades. The station features many of the original Kiss FM roster and of course Paul who was back with his Saturday night mix show ‘Trouble Time’ which he described as: ‘Not Old School. All School. Still Present! Troubgevity! Troubsolutely! Natroubley! Bless!’

It was shortly before the launch of Mi-Soul that Paul learnt the news that he had developed lung cancer. He required immediate surgery backed up by months of radiotherapy. The response of his dance music peers was immediate with the organising of a Celebrate Life event at London’s Ministry of Sound to help him during his recovery. Joey Negro, Danny Rampling, CJ Mackintosh, Phil Asher, Bobby and Steve, Norman Jay and Robert Owens, were just some of those who came out in support.

Having recovered from his treatment and with cancer in remission, Paul threw himself back into his work and music. Determined to be ‘Not Old School. All School,’ the timing was perfect as a new generation of London DJ/producers such as Floating Points and Jamie XX dipped back into soul, disco and boogie for inspiration creating a new audience ready for Paul’s magic. With his new colourful suit and hat combos, Paul was as distinctive as ever once more back where the action was in London’s new clubland hub Peckham.

He also returned to working the circuit of soulful house events and night that would see him surrounded by a musical family of people many who had known him for over forty years. It was when performing at such an event in Croatia that he felt unwell and on his return found out that his cancer had returned, spread and was likely to prove terminal.

Paul turned to music as he had always done. Those who knew Paul often heard the question that he would inevitably throw out at the end of the good night: ‘Music! What would we do without music?’ For Paul, his faith in music was fundamental, and it was this which had given him a career when such a thing didn’t exist for someone like himself and allowed him to make something of himself. Always a fighter, in Paul’s life as long as he was working and making his music he was winning.

Paul ‘Trouble’ Anderson delivered his final Mi-Soul radio show on November 11th 2018. He sadly passed away peacefully on December 2nd 2018.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.